SierraScape October - November 2007

Back to Table of Contents

by Ken Schechtman, PhD

An abiding principle of environmental justice is that race, national origin, and economic status should have no impact on the likelihood that one will be exposed to environmental pollutants. Unfortunately, an abundant body of evidence indicates that this noble ideal is far from reality. The consequences are especially acute because groups that have the greatest exposure to environmental toxins suffer frequently from parallel disparities in education and health care access. This duality of deprivation can have a devastating impact on the morbidity and mortality of those who reside near the bottom of both scales of justice.

Before discussing our own investigation of these issues as they relate to the St. Louis area, some national data can provide a useful context for appreciating the magnitude of the problem.

- A 2002 study in the journal Environmental Health Perspectives found that in every large metropolitan area in the country, African Americans were more likely than Whites to live in areas with high levels of toxic air pollutants. The broadly constituted results in this paper are consistent with numerous localized reports that establish an overwhelming inverse correlation between income and the probability that an individual will live near specific point sources of pollution.

- The 2007 Green Book published by the US Environmental Protection Agency reports that in 2002, 71% of African Americans lived in counties that violated federal air pollution standards as compared to 58% of Whites.

- Air pollution is estimated to be responsible for as many as 70,000 deaths annually and to increase the morbidity and mortality associated with disparate diseases that include heart disease, several cancers, sudden infant death syndrome, and lung diseases such as chronic bronchitis and asthma. Although they represent only 12% of the population, African Americans account for 25% of all asthma deaths.

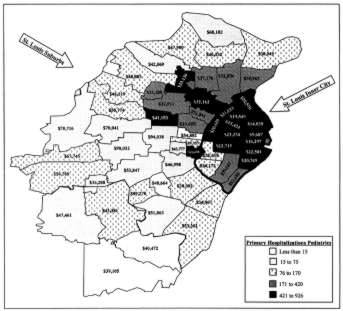

To quantify the problem in a concrete local way, I have attached a map generated for a 2001 article in the Journal of Asthma I wrote with colleagues at the Washington University School of Medicine. The demarcations on the map are zip codes in the St. Louis area and the numerical entries are census data on median family income in each zip code. As the map legend illustrates, the shading provides zip-code specific information about the annual number of pediatric asthma hospitalizations per 100,000 children. The darker shades indicate increased rates.

Annual pediatric asthma hospitalization rates per 100,000 children by zip code and median family income in the St. Louis metropolitan area. Larger map |

As can be seen from the map, the darker shades are found exclusively in the inner city and in close in suburbs. In every case, the high hospitalization zip codes had lower family incomes. Specifically, zip codes where the median family income was less than $20,000 had pediatric asthma hospitalization rates that were 8.3 times as great as zip codes with family incomes over $50,000. There were county zip codes with 0 or 1 pediatric hospitalizations in the entire year that was studied. There were inner city zip codes with similar populations that had 50 or more such hospitalizations. If the entire metropolitan area had pediatric asthma hospitalization rates equal to that of the $50,000 plus median income zip codes, more than 1300 hospitalizations costing more than $10 million would have been prevented. And this is for one disease, only for children, and does not include emergency room visits that did not lead to hospitalization.

Our data could not provide precise quantitative conclusions about the etiology of the marked disparities discussed above. It is undoubtedly the case that a substantial portion can be explained by economic discrepancies and associated educational and health care deficits. But equally certain is that some unknown portion of the asthma hospitalization disparity results from environmental injustice. Inner city areas have higher pollutants of many types, including the small particulate matter that has been repeatedly associated with asthma exacerbations and with morbidity and mortality from numerous other diseases. Inner city residents must also cope with an indoor environment that is a significant contributor to asthma morbidity, with cockroach allergens and second hand tobacco smoke being the most notable among a long list of culprits.

As we pursue the business of saving our planet from ourselves, we should recognize that we are also engaged in a fight for simple justice. The countries that will be devastated most by global warming are the poorest countries. And just as surely, as this article has sought to demonstrate, it is the poorest in our own country who are most impacted by our careless stewardship of the planet. In the most basic sense of the terms, the fight for the environment is also a fight for civil rights and for human rights.