By Charles Whitfield & Garen Checkley

When we think of thriving ecosystems, we often think about diverse old-growth forests like the Amazon rainforest. Dense, bustling cities are the human equivalent. Thinking of urban communities like natural ones opens up novel and insightful ways to consider land use policies.

It’s true: old-growth forests and dense, bustling cities have more in common than we might think. Both rely on deeply interconnected networks that evolve over time. Both are sensitive ecosystems that can be harmed by simplistic attempts to organize and homogenize them. Both are critical parts of the fight against climate change towards biodiversity and conservation.

In a thriving forest, trees, shrubs, ferns, and other flora grow alongside communities of animals and fungi where biodiversity is abundant. More than just being neighbors, each member of a forest community depends on all the others. Animals and smaller plants rely on the microclimates created by tall trees, and trees rely on these animals to spread seeds. And they even communicate with one another: trees utilize fungi in the soil that enables a “wood wide web” through which their roots share nutrients and information-carrying chemical signals. Even the death and fall of a towering tree lets in critical sunlight for younger trees and supports ecosystem renewal.

These networks are built over time, through a natural process called ecological succession. Starting from bare rock, “pioneer” species such as lichen and grasses are replaced by intermediate species of shrubs and smaller, faster-growing trees. Each new stage of the process creates the necessary environment for the next, altering soil chemistry and protecting fragile seedlings from harsh sun and wind. After decades or centuries, a mature forest is filled with the tallest, longest-lived tree species and achieves a stable peak in biodiversity.

Similarly, dense, urbanized areas are models of connections and diversity. A thriving human population has a diversity of families, community organizations, businesses, schools, and other groups that each play a vital role in the life of the city. Cities are as interdependent as a forest: residents provide each other with the goods, services, social connections, and cultural experiences needed to live and thrive. Instead of fungal connections in the soil, we use fiber optics and radio waves to stay connected.

Over time, a thriving city grows and densifies similarly to ecological succession in forests. Sparse, low-rise, car-dependent buildings make way for townhomes, triplexes, and small apartment buildings. As the city grows, it creates communities, jobs, and infrastructure that encourage yet more density and complexity. The result is a mature, dense, interconnected, and diverse urban landscape.

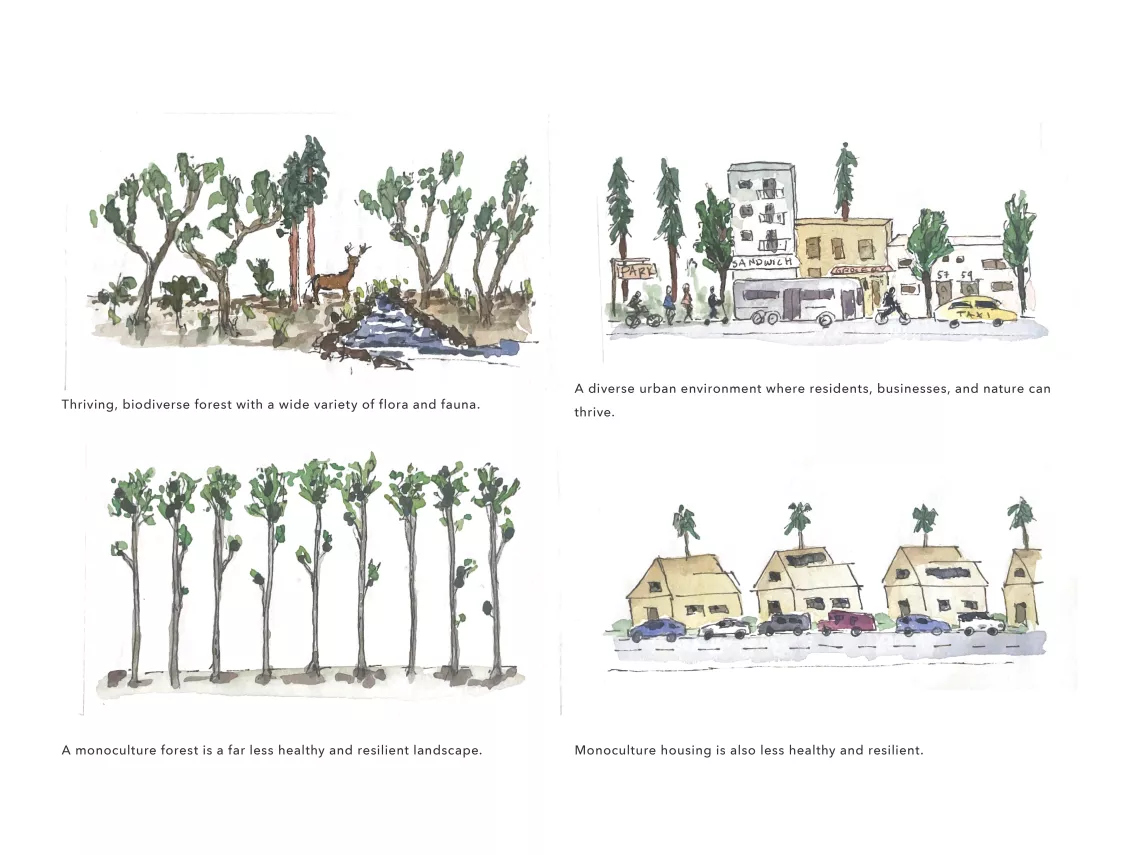

But both of these forms of communities can suffer when we try to simplify them. Man-made monoculture forests, or “tree plantations,” feature hundreds or thousands of identical trees that are far more susceptible to disease and wildfire. These sorts of forests are much less resilient than natural ones, where biodiversity helps to keep the ecosystem healthy.

The urban equivalent of this is suburban sprawl, monoculture communities like the ones that are widespread across the Bay Area and the United States. Just like tree plantations, large portions of American communities are zoned exclusively for single-family homes. Zoning laws, which were started to uphold racial segregation, now continue to separate housing and commercial areas and impose height, density, and other limits that restrict opportunities for urban biodiversity. Each part of the community is isolated, making it impossible to form the rich, resilient networks of homes, transportation, community, and commerce that a thriving city needs.

Not only does strict adherence to this rigid order make it impossible to have a wide variety of usage and building types in one area, it is also highly exclusionary. In monoculture urban planning, students and other people who don’t fit the traditional single-family-home model are priced or pushed out of suburban sprawl. When people struggle to find housing, interdependent communities are displaced or cut off from each other, and local businesses are denied patrons.

Dense, diverse communities — natural and urban — are also essential in our fight against climate change. Forests are nature’s original carbon capture technology. Trees take carbon dioxide from the air and store it in wood, beginning with the rapid growth of young forests and peaking as the oldest trees reach their full height. The taller the forest grows, the more carbon it captures. Monoculture forests, by contrast, have a poor track record of carbon sequestration.

Similarly, cities are the most carbon-efficient places for humans to thrive. Density enables walkability and sustainable public transit. Smaller multi-family homes take less energy to build, heat, cool, and fill with stuff. Residents in denser areas waste far less energy on transportation and utilities than their suburban counterparts. Because of this, allowing cities to grow upward with more density is a critical alternative to unsustainable suburban sprawl. Cities with this type diversity spread across more condensed areas allow us to efficiently use resources for human communities while preserving natural communities that would have otherwise been paved over.

The Sierra Club recognizes the need to promote this type of development in existing areas. The Sierra Club’s Smart Growth and Urban Infill Guidance advocates: “Choosing smart growth over sprawl is one of the most powerful decisions city and other local governments can make to reduce climate emissions and air pollution, conserve local habitat, and improve the health of their communities.” However, for too long communities in the Bay Area have resisted building additional homes where there’s already development. Multi-family and multi-unit buildings have been banned or discouraged by monoculture-like zoning policies and onerous processes and fees that drive up the cost of creating new homes in existing neighborhoods. Look around your neighborhood: do you see a planned monoculture, or a diverse, resilient community?

The fight against monoculture housing is seeing progress. The San Francisco Group has recently formed a new housing sub-committee and is inviting members to get involved to fight for diverse cities and dense, sustainable, transit-oriented communities.

If you are interested in getting involved in this fight for thriving, diverse, environmentally sustainable urban ecology, you can join the SF Group’s Housing Committee, or raise these topics in your local Sierra Club group discussions. The SF Group Housing Committee meets on the first Tuesday of every month. Email committee chair Danny Sauter at sfhousing@sfbaysc.org for more information.

The power to resist monoculture-like suburban sprawl and foster diverse, resilient communities is in our hands.

Illustrations by Garen Checkley.