Biking the Isle of Happy Land Use Policies

A Scotch cemetery makes for a cozy campsite

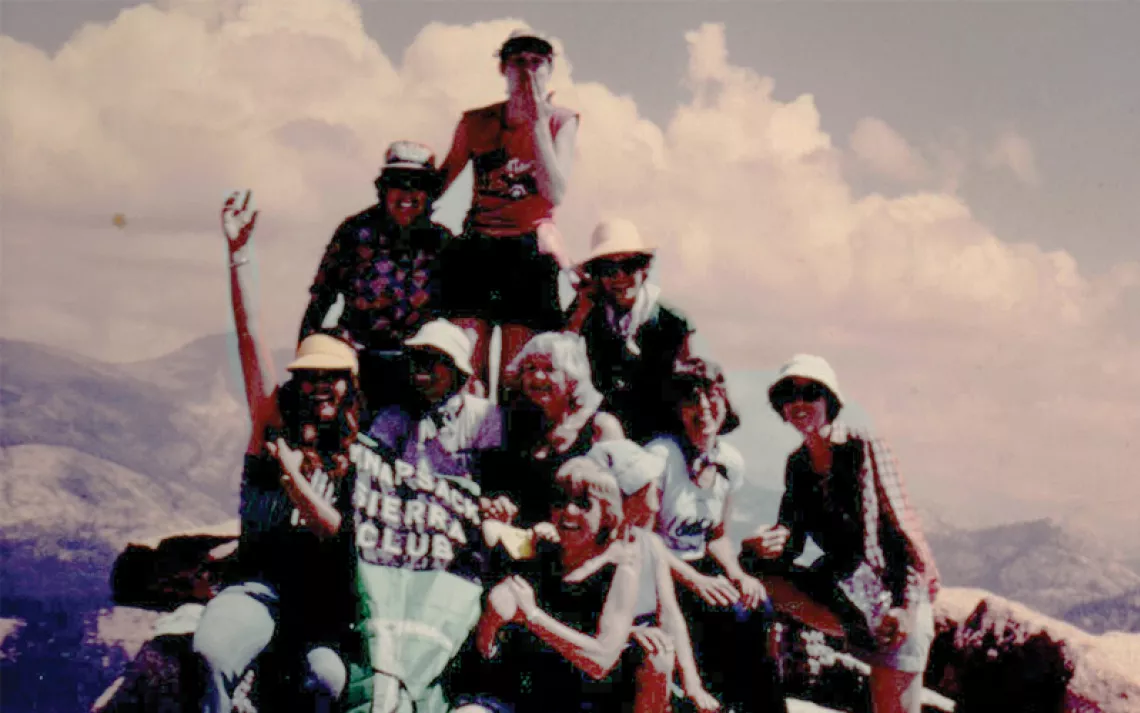

Photo by A. Contreras

We leaned our pannier-laden bikes against the low stone wall, crossed over the cattle grid, and considered our options. Outside the Politician--the sole pub on Eriskay, a tiny hump of land in Scotland's Outer Hebrides--a handful of sturdy, graceless houses faced off against the prevailing winds. Inside were central heating, carbohydrates, a restorative selection of peaty island whiskies, and a sign memorializing a 1941 shipwreck that liberated some 22,000 cases of the stuff, leaving Eriskay awash in contraband liquor. "Never in the history of human drinking was so much drunk so freely, by so few," it read. My girlfriend and I sat down at a corner table to uphold tradition while reviewing the day's dreamy eight-hour ride through misty precipitate. We still had no place to sleep.

We had heard of a field down the road where we could camp, but it just seemed so improbable. Wouldn't some irate, tweed-capped farmer come along and yell at us? Set loose a pair of wild-eyed sheepdogs? Unlikely, said the bartender when we finally went over to inquire, trying to look harmless and clean. She cheerfully gave us directions, adding that pretty much everyone passing through on foot or bike camped there--it was public land, after all. As she left us to digest this puzzling but happy concept, we raised our glasses to benevolent land management policies, and to day two of an eight-day ride that would take us from the small, southern island of Barra (population: 1,300) to Lewis and Harris (two names, one island), looming ahead at the top of the island chain.

Half an hour later, we found the field, which was adjacent to the North Atlantic and a graveyard. Tall grass streaked damply against our legs, soaking our bike shoes, and by the time our tent was up, the sky was nearly dark. On the plus side: Dusk hadn't fallen till 9 o'clock on this mid-August night somewhere around the 57th parallel, and, assuming our bartender wasn't messing with us, no one was going to complain that we'd set up camp against the seaward wall of the village cemetery.

It wasn't like camping back in California. No permits or fees. No signs of a higher authority, other than the munificent gods of wind and rain. Per the Land Reform (Scotland) Act of 2003 and the Scottish Outdoor Access Code, our only obligations were to leave no trace, jump no fences, avoid disturbing the thousands of anxious sheep that had thus far been our most constant companions, and otherwise not make nuisances of ourselves.

At home, city parks closed at dusk. At home, during a budgetary disaster that had curtailed services in state parks, we'd awakened one morning to a tapping on our tent and a polite but conspicuously firearmed ranger instructing us to be on our way. Of course, our way led back to a metropolitan area of some 4.5 million inhabitants, where it was easier to picture an imminent tragedy of the commons than it was to imagine our parklands kept safe by a voluntary code of outdoor-access conduct.

Here, the picture was different. We were six hours by ferry from the mainland, on one of 15 inhabited islands in a cluster of 200, whose total population came to around 26,000 souls. For two days we'd ridden north on narrow, empty roads, staring out over salt marshes, moors, and miles of low-tide wet sands. It was a lonely, gorgeous place, veined with lochs, more water than earth, the land a low, headlong scattering of Lewisian gneiss with a string of white-sand beaches brightening the western edge.

One of them, empty and pitted with tide pools, sprawled 15 feet from our footprint here in the Eriskay field, and we sat in the doorway of our tent to watch the light withdraw across the shallows of the sound. The rain started again. We retreated into the tent with our flask of Islay whisky. No one knew or cared we were there, and we toasted to that as well.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club