August Observing Highlights

Photo by iStock/nukleerkedi

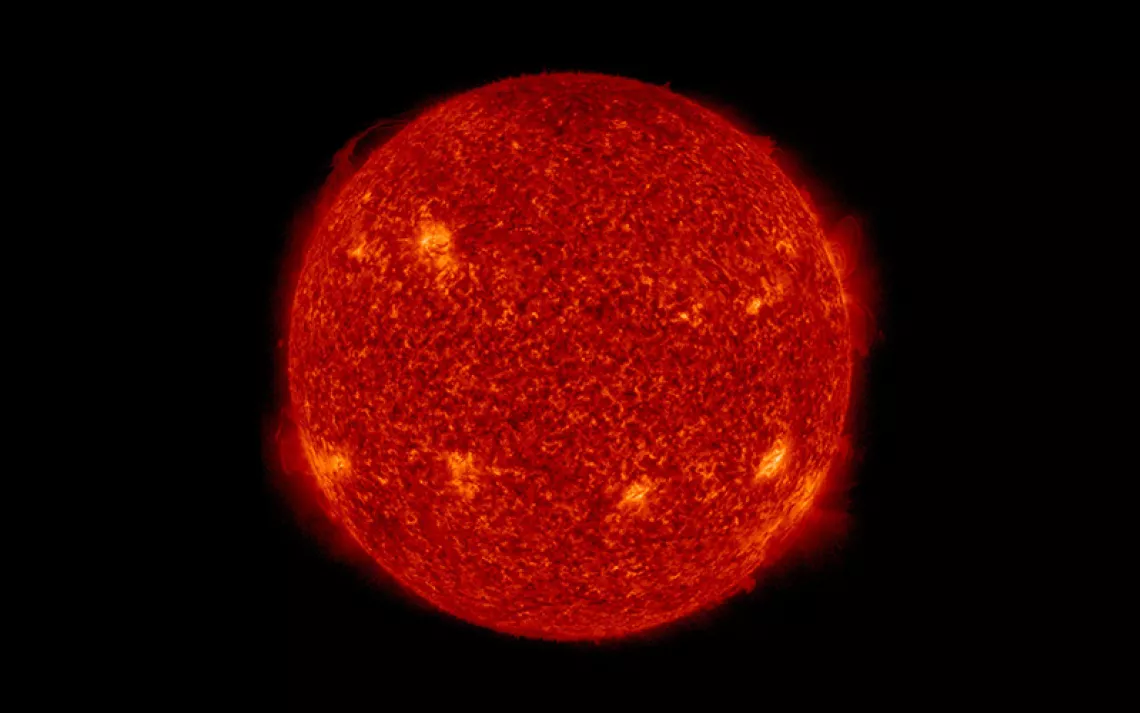

Bright Venus has been a marker in the western sky on summer evenings, beaming like a plane coming in for a landing. But in August, Venus quickly sets with the sun, leaving Saturn and Mercury to be the standout planets for the remainder of summer.

Mercury rises above the horizon but then hovers not far from it, sliding west every night until it meets with a crescent moon on August 16. On that night, Mercury, at magnitude -0.2, will be the point of light to the moon’s right. On August 19, the crescent moon slips away, growing slowly, and standing just above the star Spica. On August 22, a half-lit moon can be found beside Saturn. Take the time to view Saturn through a telescope, noting the shadows from the rings falling on the planet and the planet’s shadow falling on the rings to help you see the view in three dimensions. Then swing the telescope toward the moon and explore the mountains and craters along the terminator (day/night line).

July squeezed in two full moons, so the full moon of August won’t happen until the end of the month. On August 29 at 11:35 a.m. PDT the moon will be 100-percent lit. Of course it won’t be above the horizon at that moment, but it will still be 99.9-percent lit as it rises that night. Also on that night, Neptune will be less than three and a half degrees to the moon’s right. However, Neptune requires binoculars or a telescope to see, and the bright moonlight tends to wash out stars and planets in its vicinity, making it even more of a challenge to find the eighth planet.

With the full moon late in the month, the Perseid Meteor Shower will be nearly free of moonlight. On the peak dates of the shower, August 11 to 13, the moon will be in an old crescent phase, out of the sky in the evenings and only appearing before dawn. For many people, the Perseid Meteor Shower is the observing highlight of the entire summer. Up to 100 meteors an hour can be seen in the wee hours of the morning, but if you look after dark on any of the peak nights, you should see a fairly good display.

Watch for the meteors to trace bright, fast paths across the sky. If you follow the trails of the meteors backward, you'll see that they emanate from an area near the constellation Perseus, which gives the meteor shower its name. If you see meteors that bisect the paths of the Perseids, then you’ve spotted stray meteors that can occur on any given night.

And if you haven’t yet observed the Milky Way along the southern horizon this summer, do it tonight. The center of our galaxy lies in the direction of the constellation Sagittarius, which can be found in the south just above the horizon on summer nights. Look for stars that form a distinctive teapot shape. Another constellation that is easy to spot is Scorpius, which lies in the south-southwest along the horizon. It has a distinctive hook shape that skims the ground and a bowed arrow shape (which is actually supposed to be a pair of claws) to the upper right. If you use a telescope or binoculars to slowly scan these constellations, you should run into many “faint fuzzies” or star clusters and nebulae of the Milky Way.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club