Southern Florida's Black Line of Death

Polluted discharges from Lake Okeechobee flow down the St. Lucie River into the Atlantic. | Photo courtesy of Ed Lippisch

The black line of death is coming.

That’s the ominous warning that clean water activist John Heim has been shouting all over Washington, D.C., this past week. Heim is a Southwest Florida resident who is enraged by what he’s seeing on the beaches out his back door—and he’ll talk about it to anyone willing to listen.

What Heim calls the black line of death is a surge of mucky-brown water sliding out from Lake Okeechobee and down through the Caloosahatchee and St. Lucie Rivers. “You can see this complete line in the water where it goes from Bahama blue to black, and it’s full of bacteria and nitrogen,” he says. The water is being released to keep Florida’s largest freshwater lake—which is at record levels after heavy winter rains—from breaching the Herbert Hoover Dike.

Okeechobee's freshwater, however, is far from pristine. That's because the southern end of the lake is swaddled by the 700,000-acre Everglades Agricultural Area, a pampa of wetlands turned farmland. “About 80 percent of it is sugarcane,” says Paul Gray, PhD, an ecologist with Audubon Florida. For decades, farmers pumped wastewater off the fields and into the lake, making it a cesspool of phosphorous and nitrogen. In recent years, tougher regulations have curbed this practice, but runoff is still a major issue. According to an investigation by the Orlando Sun Sentinel, 62 percent of all the phosphorous that gets dumped into Lake Okeechobee comes from sugar fields in the Everglades Agricultural Area.

The high levels of pollution are one reason that the water can’t be sent southward into the Everglades—which would have been its traditional path. Currently, the lake's water quality would not pass muster with the EPA. So, while the Everglades slowly die of thirst, too much water is being sent down the St. Lucie and Caloosahatchee Rivers.

“The Caloosahatchee needs to maintain some freshwater flow to keep the salinity levels steady to protect the estuaries,” says Gray. “So a little bit of flow—about 2,000 acre feet per day—is okay. But what they’re getting right now is 18,000 acre feet. It’s way too much.”

These massive freshwater flushes will likely cause widespread seagrass and oyster bed die-offs. “This is extremely serious, and we could be living with the consequences for years,” says Tom Van Lent, PhD, the director of science and policy for the Everglades Foundation. Ironically, while seagrass beds are dying because of too much freshwater on the east and west sides of the state, in Florida Bay, the southernmost tip of the Everglades, they are dying because there’s not enough freshwater and salinity levels are too high. “Eventually all that dead seagrass will begin to rot, and we may get a large, toxic algae bloom,” says Van Lent.

Meanwhile, the black line of death creeps down the coast—horrifying residents, tourists, and snowbird retirees and bearing witness to a century of bad environmental policy and water-systems mismanagement. Back in the early 20th century, developers, big agricultural interests, and the federal government agreed that Florida would be more useful without those pesky swampy bits. The Army Corps of Engineers built a massive dike around Lake Okeechobee, blocking the Everglades’ main water source. When the Herbert Hoover Dike was completed, thousands of acres of pristine sawgrass prairie started drying up—and dying—almost immediately.

“What’s happening today was how the water management plan was designed to work,” says Van Lent. “This is ecological collapse on a large scale; Everglades National Park is in very serious trouble.”

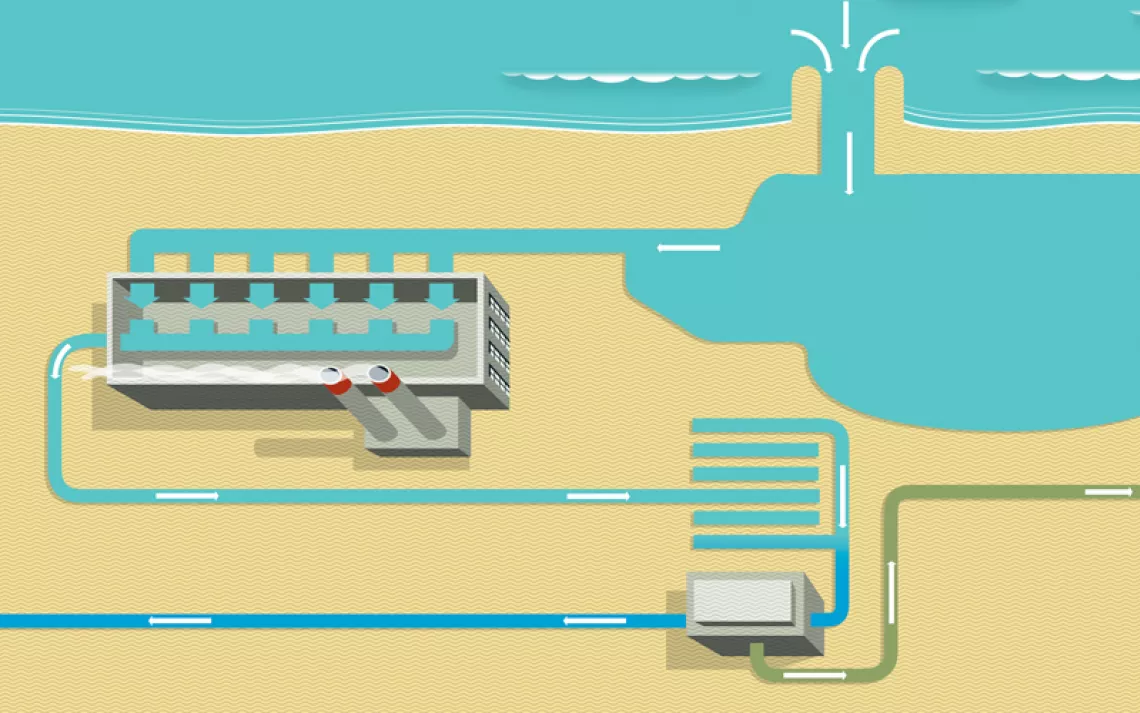

In one small bright spot, the South Florida Water Management District announced on February 15 that some water would be diverted into Everglades National Park as an emergency measure. This water is coming from a storage facility called Water Conservation Area 3, an artificial wetland on the southeast side of the park. Van Lent sees this rerouting of water as mostly a good thing, since the Everglades are so parched. However, it’s still not going to allow water to flow to where the Everglades need it most. “The water management system was not designed to let the water flow into the deepest parts of the Everglades,” he says. Instead, water will flow into the Everglades’ flood bank areas. (Unfortunately, these flood bank areas also happen to be prime nesting sites for one of the most critically endangered birds in the United States, the Cape Sable seaside sparrow.)

Linda Friar, a spokesperson for Everglades National Park, says that the park sees any flow of water into its boundaries as a good thing. Ecologists and hydrologists are monitoring the flow, she says, and will evaluate in 90 days whether the water will continue to be allowed in.

Water Conservation Area 3: Part of the Everglades solution. | Photo courtesy of the Everglades Foundation

Bringing water in from Conservation Area 3 has actually been a longtime goal of the Everglades Restoration Plan, a comprehensive proposal to restore water flow to the Everglades put into place in 2000. Sixteen years later, however, very little progress has been made toward implementing the plan. It took the high water levels in Lake Okeechobee to force the hand of the South Florida Water Management District and bring about this small step.

Until the Everglades Restoration Plan is fully implemented—which both Van Lent and Gray say is more than a decade away—the water from Lake O will continue to flow east and west but not into the Everglades where it’s needed the most. The black line of death will continue its march through the coastal estuaries, leaving dead seagrass and oysters in its wake. The shorebirds will lose critical nesting grounds as the water levels rise, and the snowbirds—one of Florida’s biggest economic drivers—may decide to pack up and go home early.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club