Kayaking Chile's Pascua River in Search of an Untamed Landscape

A journey through Patagonia explores what it means to engage in "rugged play."

Photography by Tyler Williams

The remote beach was empty except for me and my companions. The broad expanse of sea was empty, too, and I squinted at the horizon, looking for a human shape. This was two years ago, deep in southern Chile, and five of us had just descended the bottom section of the Pascua—a burly, glacier-fed river—by kayak. We were at the Pascua's mouth, where it empties into a fjord, and we were planning to head through the fjord to the small town of Caleta Tortel. Two of the kayakers from our party, Lisa and Roberto, had paddled ahead until they disappeared amid the chop. Now, I was trying to find them in this gray-green world.

Seeing no sign of them, I walked back to the riverbank and kneeled for a drink of agua dulce—freshwater. Cold slid down my throat. The air smelled sweet, of mist and storms, and clouds were slung low above the water. Waves jostled and splashed, and I breathed deeply, readying myself for what I knew I had to do next: paddle through the tumult that Lisa and Roberto had just vanished into.

There was nothing for the three of us left on the gravel bar to do but load into our boats and point them toward the inlet. The other lives we all lived—an existence with things like showers and email and beds—had become laughably unimportant. Our needs were immediate and self-evident. Stay alive, stay dry, stay together, and keep going. Or turn back. But we had no intention of turning back. We gripped our paddles and pushed off the bank.

Where the river hits the sea, we hit the waves—heaving pyramids of whitecapped water that splashed over our spray skirts. My boat partner and I counted aloud to pace our strokes—one, two, three, four—as we dug our paddles into the dark water, hoping that if we paddled hard enough for long enough, we'd stay upright and make it to the nearest shore. Our kayak, about 17 feet long, rose onto the swells, hung in midair, then slammed back down. I clenched my paddle tighter. My forearms stiffened and ached. The land, the water, the weather—all of it became real and close. Although nerve-racking, this was the kind of intensity I lived for. It pulled me into the present and put all of me to work.

We aimed our boat for a beach that we could see between the waves. As we got closer, I spotted two life-jacketed figures pulling brightly colored plastic boats ashore. Lisa and Roberto had made landfall.

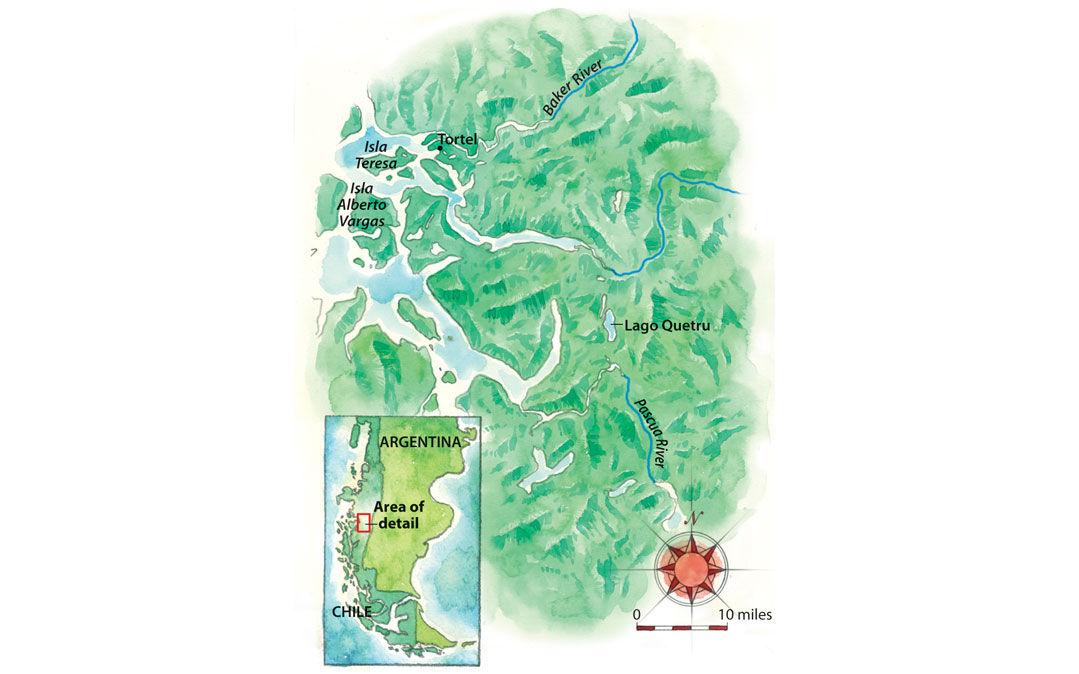

The paddlers' route from the Pascua River to Caleta Tortel, in Chilean Patagonia. Illustration by Steve Stankiewicz.

Why was I there, paddling as hard as I could on those stormy seas? There's more than one way to answer that question. The Pascua is in a region of Chile called Aysén. I'd spent the past couple of years there doing research on a proposal to build five large dams, two of which would be on the Pascua. During the course of that project, I had learned a lot about river flows, hydropower, and electricity transmission lines. But I wanted to know the river that I had thought about so much in a more intimate way. Before the Pascua's power turned to megawatts, I wanted to feel its current against my skin.

I was also in Aysén for less practical reasons. Like many others before me, I'd been drawn by the idea of Patagonia: a place where wind and weather ruled, granite spires rose from the earth, and teal rivers curled through a trackless steppe. Parts of Aysén are practically uninhabited, with less than three people per square mile—a lower population density than that of the Sahara Desert or Mongolia. I'd hitchhiked through the region, kayaked its rivers, and explored its valleys, trying to get closer to the place I'd been so fixated on. The ecological philosopher Arne Naess wrote that mountaineering is a way to participate in a mountain's greatness. In the same vein, everything I did in the far south was part of my attempt to participate in the greatness of that landscape.

The Pascua encapsulates all that is wondrous about Patagonia. Other rivers in the area, like the Baker, are strewn with ranches, but very few gauchos—South America's version of cowboys—live along the Pascua. Those who do first arrived in handmade wooden rowboats. To get up the river before motorboats, the gauchos had to stand on the thickly forested banks of the Pascua and pull their boats (which were sometimes full of lambs) upstream with ropes. A spur road from the dirt highway did not arrive until 2006. The Pascua was remote, powerful, isolated—a force to be reckoned with. As a few friends and I talked about a potential trip on the river, we began referring to it as "the wild and unknown Pascua."

So, we decided that in February 2014 we would kayak the lower Pascua from near Lago Quetru to the shores of Tortel. Our crew would be Weston Boyles, a then-27-year-old Colorado native; Tyler Williams and Lisa Gelczis, husband-and-wife guides from Flagstaff, Arizona; and Roberto Haro, a middle-aged gym teacher from the town of Cochrane who taught local kids how to whitewater kayak. The four of them had met through an organization Weston started, Rios to Rivers, which had facilitated an exchange between some of Roberto's teenage kayakers and some American kayakers to paddle the Baker and Colorado Rivers while learning about the effects of dams.

Simply getting ready for the trip was challenging. There were no reports from other paddlers or even any detailed maps. So we huddled around a laptop in Roberto's kitchen, scrolling through satellite images to sketch a route.

Maps of the area show a shredded coastline where the continent encounters the sea. Islands are splattered across bays, and fjords slice into the mainland, carvings left over from the last ice age. Patagonia's topography is similar to that of Southeast Alaska and Norway, except with more places where glaciers meet the sea.

The journey promised heavy rain, cold temperatures, and high winds. Friends of ours could not understand why we would suffer through it. When we told people in Cochrane that we would kayak from Lago Quetru to the mouth of the Pascua, then up the coast to Tortel, one person asked, "Do you want to die?"

I struggled to explain why we wanted to go there. I often felt like using the clichéd response: "If you have to ask, you'll never understand." What drives anyone on this kind of quest? For me, it came from a desire to be part of something giant and wild, a yearning to participate in something beautiful. To do that fully, I needed to give up control.

At the beginning of our journey, on the banks of the Pascua, we had packed our boats and loaded them into the water. The river was so wide, it often looked like a moving lake. Boils wrinkled the surface. The water split into braids around sandy shoals and bent sharply around unnamed mountains. We paddled up creeks and made sandwiches with manjar (Chile's version of dulce de leche) on our spray skirts. On our second day, we reached the Pascua's mouth, where the river emptied into the fjord and where our group dispersed and came together again on that wind-whipped beach to wait out the bad weather.

We took naps and ate snacks and read books, then eventually set out again. Frothing water exploded against cliffs to our left. To our right, the sea spread outward until it welded itself to a skyscape of gray clouds. No more beaches appeared on the coast. The headwind blew so hard that if we paused our paddle strokes, the Klepper went backward. I couldn't stop to scratch my nose. Weston and I synchronized our strokes. Much of the time, we couldn't see our friends.

After four hours of struggling against the wind, we ducked into a protected cove where iridescent clumps of ice emerged from the dark water—sedan-size pieces of glacier that had calved off from a tongue of the Southern Patagonian Ice Field. Most of the mountains had darkened by that time, except for one ridge behind us that was gilded by the only shaft of sun we had seen all day.

We paddled toward the coast, to where a few of these icebergs were beached on the front lawn of an abandoned ranch. Aysén is a ranching region, settled by homesteaders in the early 20th century, when border tensions with Argentina led the Chilean government to give away free land. Though more and more Ayséninos are moving to towns and making a living from tourism, the region remains a gaucho stronghold. These hardy souls live the life that many people hope will continue but few people want to live themselves.

We poked around the ranch—walking around the sagging fence that surrounded the cabin, pushing through the overgrown bushes, peeking into the shed where the family once hung their meat. Richard White, a Stanford environmental historian, has written that outdoor recreation like kayaking and mountaineering represents a type of "rugged play" that mimics the hard life of the pioneer. We gringos were trying to re-create the experience of those early gaucho pioneers—only we were doing it for entertainment rather than survival.

This rugged play demands that we use our bodies to move through the land until our thighs quiver and burn, our calves tighten and tire. It also demands that we look closely at whatever is around us: rapids and waves, discoloration and indentations in snow-covered ice, the outcroppings and contours of rock. We often feel closest to the land when it requires attention and labor from us, and so such play is a way of reconnecting to the earth. Among those of us who work with papers and pens, screens and keyboards, rugged play represents a kind of nostalgia. It's a yearning for the days when we knew the land the way the family at this ranch would have—when we knew it because we had to know it, when we knew it with our bodies.

My musings were swept away by the immediate demands of hunger, cold, and fatigue. We set up our nylon tents near the old wooden buildings, made fire and food on the beach, and slept.

We woke the next morning to wind hurtling over the water. The waves were even larger than they had been the day before. We set out, making spurts of progress up the coastline. I had a plane to catch in four days, but it was foolish to believe that we could control our rate of progress.

The next several days blurred together: a montage of driving wind and rain, Weston yelling at me whenever my hood wasn't up, and paddling furiously whenever the wind abated. We hung around on beaches when the weather was especially bad, then got back in our boats during the small openings when the wind died down.

One morning, we reached a beach at the tip of the string of islands we had been following since leaving the icebergs. The beach faced a seven-mile open crossing. The weather remained windy and wavy, with whitecapped water and biting gusts. There was no way we could head into open water in such conditions, so we waited again.

We knew exactly how much food we had left: two rolls of coconut cookies, two packets of saltine crackers, a bag of oatmeal, a bag of pasta, a few pieces of stale bread, and three bags of dried milk. The five of us shared half a bag of pasta for dinner.

The next day, the rains fell so heavily and continuously that Lisa and Tyler never took off their dry suits. The rest of us shivered in soaked-through rain gear, holding our pruney hands over a fire, taking turns gathering wood. At one point, Lisa and I walked to a nearby beach and heaved large rocks onto pieces of driftwood, trying to split them, joking that we'd become cavewomen.

None of us mentioned our hunger. We had chosen to give up control, and there was nothing we could do now but wait out the wind. We were all elated that night when Roberto caught a small fish. I ate the head—including the eyes. Tyler, who doesn't smoke, asked for one of the cigarettes we had brought as gifts for gauchos. He thought it would lighten the mood.

In the beginning of the trip, when optimism and awe had reigned, we'd fondly nicknamed each snacking and sleeping spot. Tranquilo Bay. Love Beach. We dubbed this waiting spot Desolation Cove.

The next morning, hope displaced our desolation. Smaller waves passed by, free of whitecaps. We packed up our gear and readied our boats in silence, pointing our bows toward the lanky waterfalls and forested mountains that we could see across the open water. New snow dusted the peaks.

We crossed the previously treacherous passage with ridiculous ease, aiming toward a gap between the continent and an island. The seven miles passed quickly. We soon entered a protected channel, drifting by misty cascades and a curving coastline, enjoying Roberto's secret stash of lollipops and opening up the two emergency rolls of coconut cookies. We were giddy with proximity. There were no more open crossings between us and Tortel. We guessed that we would make it to town that evening.

Midmorning, we spotted a gray wooden boat in a cove. Since reaching the mouth of the Pascua, we'd seen some detritus left from human activity on a few beaches—two deserted and collapsing cabins, empty gas canisters in the sand, rusty nails in pieces of beached wood—but this boat seemed to signal that someone was close by. A tin roof caught light between the trees. We could see chickens and dogs moving about, laundry swinging from a line, and smoke puffing from a chimney.

A couple stood outside the house, both wearing black rubber boots and baggy pants. We landed and walked up to their cabin. The man had a mustache, a hat, and a tentative posture. The woman had a wide smile and thick hair that fell around her ears. She exuded enthusiasm as soon as we introduced ourselves, ushering us into her house for mate, the ubiquitous South American tea sipped through a metal straw, and apologizing for the mess. They didn't get many visitors, she said.

It was a simple one-room cabin with a wood-burning cookstove in the corner. In another corner, clothes were piled on top of a mattress. Newspaper, pieces of cardboard, and a poster of the Virgin Mary covered the walls. A flattened cat food box was pressed against the door and often flapped, letting the wind enter. We sat shivering around the stove, swallowing mate, then bread, then rice, then fish. I was awed by the intense abundance; even the plate was warm. I went back for more.

We described our trip to the couple. The woman nodded. She told us that she'd grown up on the unoccupied ranch near the Jorge Montt Glacier—the ranch where we'd camped next to icebergs. She'd had to cross from there to Tortel many times as a child. It was the route her family had taken to get to town.

When we described Desolation Cove, she nodded again, adding that the wind always blew hard there. Once, she said, she had waited at that spot for seven days before she could cross the channel. Often, gauchos would wait together on that beach, all on their way to Tortel and all stopped by the wild winds of the open channel. Many would bring lambs in their boats for beachside asados. They would make tortas in the sand.

What many in Cochrane had warned us would be a lethal journey was, for the gauchos, just part of their routine. Our rugged play had once been someone's commute.

In the following days, after we reached Caleta Tortel, forces other than wind, weather, and water would take control. I'd hitchhike hundreds of miles to the nearest airport, try to weasel my way onto an interhemispheric flight, and apologize to my professors for being late to a new semester. I'd be quickly jolted back into a life of papers and pens, screens and keyboards, showers and email and a bed.

But those gauchos, of course, would stay, and often I would think of them: still there, watching the water, waiting out the weather, intertwining their lives with the land and paying close attention to its details. I was only a visitor to that place the gauchos call home, but paddling was my way of weaving the land and sea into my life. Beyond the picture of a place, the postcard version of it, was the possibility of participation.

Salvation for the Pascua

When my friends and I kayaked the lower reaches of the Pascua River in early 2014, we thought we were undertaking a kind of farewell adventure. For eight years, Chilean environmentalists and their international allies had been fighting to prevent the construction of five dams on the Pascua and Baker Rivers. Many people feared that the dams were a done deal and that these wild rivers—gems of rugged Patagonia—would become reservoirs.

Then a massive citizens' movement overturned the political conventional wisdom. Anti-dam protests in Chile's south and marches in the capital, Santiago, made the dams a major issue in the 2014 presidential campaign. Not long after President Michelle Bachelet came into office, her cabinet voted to cancel the dams.

The decision was a landmark victory for Chile's environmental movement. Today, the Pascua and Baker Rivers continue to flow freely.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club