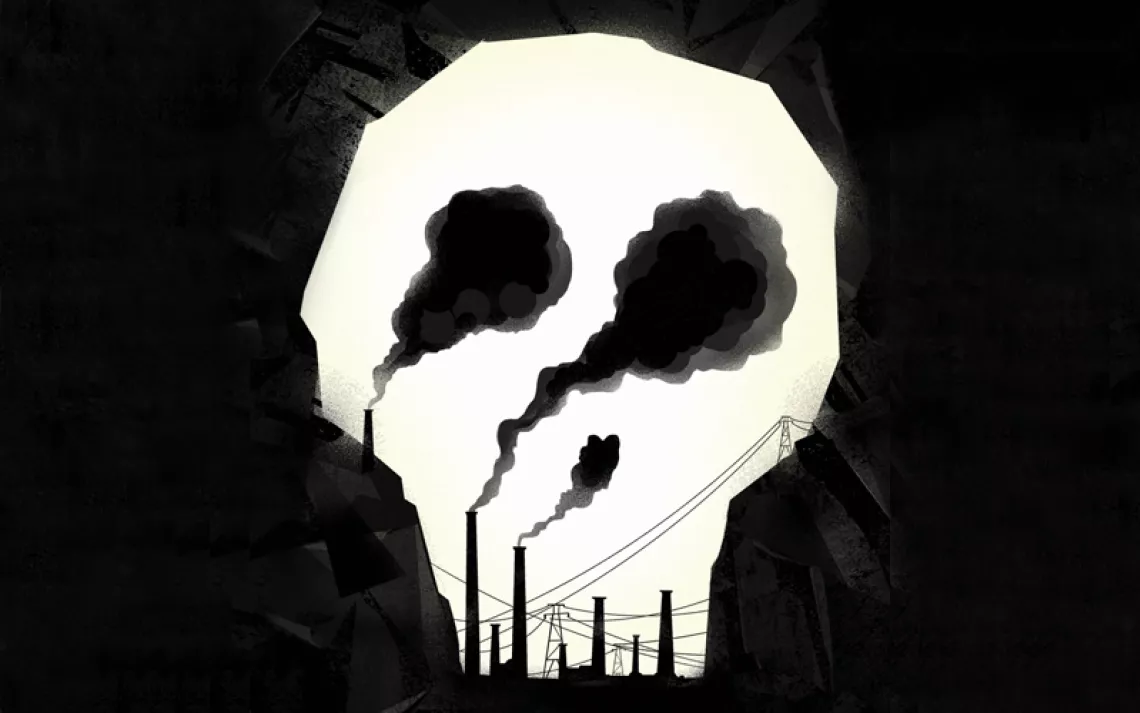

Coal-Country Scam

Coal companies devastate landscapes, go bankrupt, and stick taxpayers with the cleanup

Alpha Natural Resources promises to clean up its Edwight Mine in West Virginia—if it doesn't go bankrupt (again). | Photo by Vivian Stockman/OhVEC/Flyover courtesy of SouthWings

Viewed from a satellite, West Virginia's mountaintop-removal mines are ash-gray scabs surrounded by the deep green of Appalachia's hardwood forests. At ground level, the vast mining sites exhale clouds of asthma-inducing coal dust and poison watersheds with selenium, arsenic, and sulfate. Cindy Rank, who chairs the mining committee for the West Virginia Highlands Conservancy, has spent decades fighting the practice. Now, as the U.S. coal industry slouches toward extinction, she has a new concern.

"If [the coal companies] leave and don't have any money to take care of the problems that they're leaving behind, then everybody's in trouble," she explains. "Those of us who are citizens of Appalachia and West Virginia will be paying one way or another—with our money or with our health."

Currently, half of U.S. coal is mined by companies that either are in bankruptcy or have recently emerged from Chapter 11. These include Alpha Natural Resources, Arch Coal, and Peabody Energy, three of the top four coal companies. Concerned about what that might mean for taxpayers in January, the federal Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement (OSMRE) asked regulators in Wyoming, Colorado, New Mexico, Indiana, and Illinois to clarify whether these companies have the resources to do the promised cleanup of their mining sites.

"Even at a time of financial distress, it is still the responsibilities of these companies to do the reclamation that they signed up for," Interior Secretary Sally Jewell said in February. "We need to make sure that those companies are held accountable."

Under the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977, mine operators are obliged to reclaim the land they're mining and provide financial assurance that the reclamation process will be completed even if the company goes under. That assurance is supposed to come in the form of a third-party bond, but Congress built in a huge loophole: The largest mining companies are allowed to "self-bond," telling regulators, in essence, "We're such a large, stable, and solvent company that you don't have to worry about us going out of business."

Today, with coal in steep decline, no company's future is guaranteed. Nationwide, more than $3.86 billion worth of reclamation obligations are self-bonded—$2.4 billion of which are held by companies that are in, or have recently emerged from, bankruptcy.

The state with the most self-bonding is Wyoming, largely because its surface mines are so enormous. But coal from its vast Powder River Basin is relatively inexpensive to produce, so these mines are more likely to survive than those in Appalachia. Neither Tennessee nor Kentucky allows self-bonding, but West Virginia is rife with it. Should a company there go belly-up before starting the reclamation process for one of its vast mountaintop-removal mines, the toxic lunar landscape could persist for decades, with poison leaching into waterways and coal dust blowing into homes and schools.

Peter Morgan, a staff attorney for the Sierra Club, calls this "the nightmare scenario," but notes that thus far no bankrupt company has defaulted or liquidated. If one does, however, all its self-bonding obligations will fall to the state. That puts regulators in a pickle when coal companies reorganize. On the one hand, states don't want to be left holding the bag. On the other, they don't want to push too hard for companies to assume more responsibility for reclamation, fearing that the extra up-front costs could cause further bankruptcies.

Jeremy J. Nichols, the climate and energy director for WildEarth Guardians, calls such concerns shortsighted. "States need to make reclamation as much of a priority as coal extraction," he says. "In theory, for every acre of land you dig, there's another acre you should be filling in, but that's not happening. So it's not a matter of keeping them in business; it's getting them to understand that reclamation is part of their business. They're good hole diggers, but they're not so good at filling in those holes."

In July, a court approved a plan allowing Alpha Natural Resources to emerge from bankruptcy. Some of the company's more lucrative mines will be spun off to a new company, Contura Energy Inc. Under pressure from federal regulators, Contura will replace its self-bonded reclamation obligations in Wyoming, estimated at $411 million, with collateral bonds that are backed by assets and third-party banks. But Alpha will continue self-bonding at its riskier, less-valuable West Virginia mines—an arrangement that makes little sense, considering that the company just emerged from bankruptcy. "It's hard for me to find a way to read the law that actually allows something like that," Morgan says. In August, OSMRE strongly suggested that states not allow self-bonding in the future, and that they conduct "a thorough inquiry" into whether companies currently doing so meet the financial requirements.

Peabody Energy, for example, is now going through bankruptcy. WildEarth Guardians is concerned that its $1.4 billion in self-bonded reclamation obligations exceeds its net worth. Were those costs factored into Peabody's balance sheet, Nichols argues, even Powder River Basin coal would be unprofitable.

"Filling in these pits that are thousands of acres in size is a challenge," he says. "We're talking about billions of dollars of cleanup liabilities."

This article was funded by the Sierra Club's Beyond Coal campaign (beyondcoal.org).

WHAT YOU CAN DO

Tell the Department of the Interior to put a complete stop to the self-bonding of coal mines. Sign the petition at sc.org/bonding.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club