The (Poi) Power of Hawaiian Food Sovereignty

For some Hawaiians, reclaiming traditional food systems is a path to independence.

Daniel Anthony scoops a handful of soil from his backyard farm in Kahalu'u, Oahu.

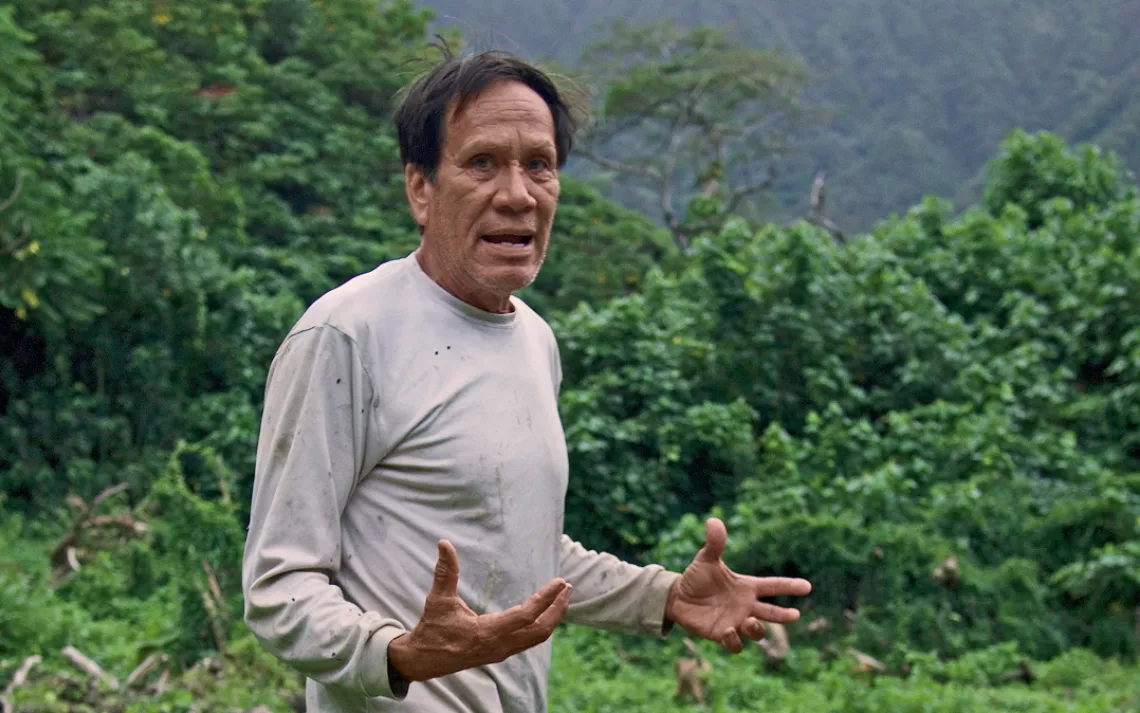

Daniel Bishop—"Uncle Danny" to the locals—is waiting for me beside his dented red pickup when I pull up to a locked gate in the town of Punalu'u, on Oahu's northeastern shore. A rugged tropical valley opens up behind him, the tops of the shark-toothed peaks streaked with clouds. A sinewy 62-year-old in a mud-smeared shirt, Bishop extends a hand the texture of coarse sandpaper. He looks down at my new flip-flops and offers a wry smile. "Brah, you don't know what you've gotten yourself into."

Bishop is one of a growing number of farmers looking to revitalize Native Hawaiian agriculture and reorient the islands' economy and food system around local, traditional, organic produce. A respected elder, he's been a member for two decades of 'Onipa'a Na Hui Kalo (roughly "steadfast are the taro farmers"), a consortium working to restore ancient farming practices.

Danny Bishop stands atop the remnants of ancient taro complexes in Punalu'u, Oahu.

For decades, Native Hawaiians have sought greater independence and a semiautonomous, sovereign government. Farming in the old way, for some, is a deeply political act.

Bishop, his son Hanale, and his partner, Chance Tom, have been farming taro on 12 acres in the nearby Waiahole Valley for a decade. He wants to show me his latest project in Punalu'u: a parcel he's been leasing for the last two years from Kamehameha Schools, Hawaii's largest private landholder.

As we bounce along the road toward the farm, Bishop explains the cultural significance of taro through the Hawaiian creation narrative: It began with the gods of sky and earth and their stillborn child. From the body of the child, called Haloa, grew a taro root—a crop that for centuries islanders have pounded into poi, the islands' porridge-like staple. Hawaiians believe that taro is inseparable from the land, or 'aina, on which it is grown. To eat poi is thus to commune with the ancestral history of the islands themselves.

The story takes on new dimensions as we enter the valley, a mere hour from Honolulu's sprawl of asphalt. Red blooms of hibiscus punctuate an impenetrable wall of greenery. Scattered among the native flora are breadfruit, banana, and Malacca apple, feral progeny of plants that were cultivated for centuries on the Hawaiian Islands and once supplied roughly enough food to feed the islands' entire population.

"Five hundred years ago, we were eating 10 pounds of poi a day," Bishop says, gesturing to the irrigation ditches and rock walls covered in vegetation, remnants of ancient taro complexes, or l'oi, that once filled this valley. "Our ancestors were poi-powered."

Unlike the corporate pineapple, sugarcane, and macadamia farms that have blanketed large swaths of the islands since colonization, the farms of ancient Hawaii were guided by a sense of shared responsibility, known as kuleana. "The chiefs had a reciprocal responsibility to the people and the environment," Bishop says. "And the people had that same reciprocal responsibility to the environment and the chief."

When Captain James Cook arrived on Kauai in 1778, there were about a million people living on the Hawaiian Islands. Then smallpox and other European diseases ravaged the native population. Within a century, around 50,000 Hawaiians remained. The islands' traditional food system was destroyed.

As a result, Bishop says, native foods, including poi, lost their central place in the Hawaiian diet, leading to major health problems. Today, obesity is epidemic; the rate of diabetes is more than twice as high among Native Hawaiians as among the white population in the United States. The rate of coronary heart disease is three times as high.

Bishop sees the restoration of this small farm—and, by extension, the effort to inspire new taro farmers across the islands—as an obligation to future generations. "This might seem like looking at the past, but it is all about the future."

New taro farmers face substantial obstacles: limited access to water, low market values for taro, and Hawaii's increasingly expensive and scarce agricultural land. Yet their ranks continue to grow, according to Penny Levin, a restoration ecologist and longtime taro farmer in Maui. "The number of people who could pound poi with a board and stone has gone from a small handful of kupuna [elders] in the 1980s to thousands of youth and makua [parents] today."

Rebuilding Hawaii's ancient food systems means regaining lost knowledge—and the complexity of those systems is just beginning to be understood. One key finding is that intensive agriculture was practiced not only in well-watered valleys on the rainy windward sides of the islands (as on Bishop's farm in Punalu'u), but also on the arid leeward slopes. "Adaptability is a hallmark of traditional Hawaiian agriculture," says Noa Lincoln, an assistant professor of tropical plant and soil sciences at the University of Hawaii at Manoa. On the arid western side of Kohala Volcano, for example, an intricate latticework of ancient stone-and-earth walls was likely planted with sugarcane, which acted as a windbreak and helped draw moisture from the air.

Contrast that with the industrial monocrops that now dominate Hawaii. Today, around 80 percent of the food grown on the islands is exported. In this land of tropical bounty, the behemoth of Midwestern agriculture, corn, has become the state's largest cash crop.

Daniel Anthony is a renowned poi-maker and a strong believer in the connection between traditional food and Hawaiian identity. I visit him at his farm, located behind his home in a nondescript suburban neighborhood in the East Shore town of Kahalu'u. He and his wife, Alohi, harvest almost enough food to feed themselves year-round.

Anthony is challenging the prevailing model of how Native Hawaiians feed themselves. In 2009, after perfecting his knowledge of the poi-making trade, he started a poi business, donning a traditional Hawaiian loincloth and pounding poi by hand with simple stone tools. The seemingly virtuous act drew the ire of the state health department, which issued a cease and desist order.

But Anthony's poi was so tasty, he also drew the attention of Ed Kenney, a rising Honolulu chef, who put Anthony's contraband fermented pa'i'ai (a concentrated form of poi) on the menu of his noted restaurant, Town, in Kaimuki. That same year, Anthony ran a popular community taro-pounding night attended by thousands. "From September to May, 3,000 people had come through our weekly poi-making night," he says. "We realized we couldn't sell you pa'i'ai, but we could teach you how to make it."

Eating is a powerful declaration of sovereignty, Anthony says—and the means by which Native Hawaiians will regain their independence.

"This is how we build an army, brah."

This article appeared in the March/April 2017 edition with the headline "Poi Power."

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club