Reading the Quran Connects Me to Nature

Beside a cool stream, I unwrap the sacred text from my mother's scarf

Before I take the sacred text out of my backpack, I dip my hands in the cool rush of the creek that runs into the city below. Doing so, I connect myself to the inhabitants of the valley and all beings on this planet that this water may have cycled through. I'm in Big Cottonwood Canyon, a watershed that supplies drinking water to Utah's Wasatch Front. Two hydroelectric plants are nestled among the conifers. I push my hands into the water to feel the slipperiness of rocks soft as the underbellies of fish. I am connected to the sea by the perfume of algae and brought closer to the scent of whales.

I've brought the Quran with me. Precious care is given to the Quran as the most sacred of texts. Tradition forbids the book to touch the ground, and it must always be held with clean hands. I unfurl the book from my mother's scarf, in which I'd wrapped it for safekeeping, and take a seat amid a landscape brushed by dark greens and the gray of oncoming winter.

I carry my traditions with me in a backpack, into wide-open spaces, to tie the threads of sacred goodness and common divinity. My family is Muslim but culturally connected to Hinduism, and through the landscapes of Utah, I am blazing my own spiritual trails. Being an American who is part of the Indian and Pakistani diaspora, I often feel that I do not belong to either human-designated pole, so the more-than-human world is my refuge. Among these spaces—the wide, black-eyed communities of aspen and the cool seats in amphitheaters of redrock—my identity is planetary citizen. I am a citizen of Earth in the silence and soil of the canyon, in the shadow of oblong hoodoos. I am an earthling today, sitting, trying to read the Quran in English, to cast my net further into the waters of past and present.

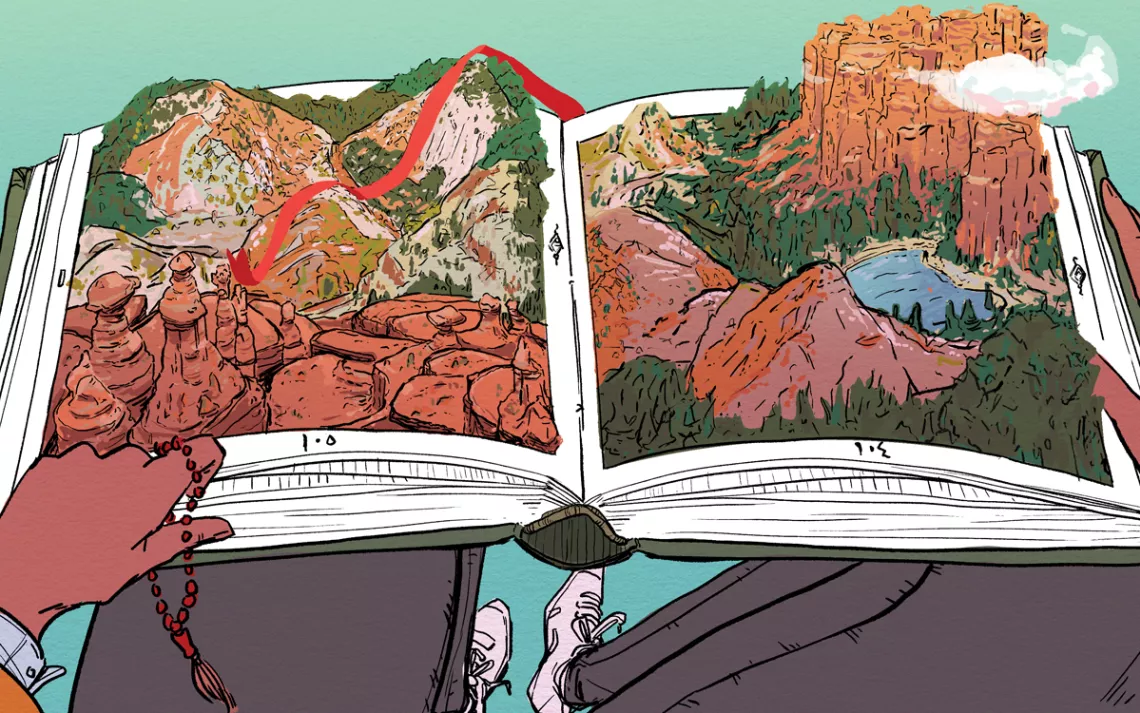

Illustration by Sara Alfageeh

After the Prophet was born, he was sent to live with a Bedouin family, because culture and custom held that the desert landscape, away from the noise and pollution of civilization, nourished growing bodies and minds. The young Prophet spent his childhood in a land of rippling and coiling sand, similar to this redrock country. He talked to camels in markets, holding their oblong faces that dip down due to the gravity of their heavy necks, soothing them and instructing people not to idle on their backs.

Once, when I was in Big Cottonwood Canyon, I saw a moose. Her stance paralleled mine, and our eyes met in a shared moment of mammalian intimacy. I realized that our eyes were the same color. In that moment, in my distance and respect, I considered how both our bodies and our lands are mistreated. We held each other in one another's gaze, the same color as the soil and sand that has shaped the world.

The sun sets, and I curl up with a blanket stitched by my grandmother, my Nani, and sleep for an hour under the Dog Star. I dream not of Utah's January smog but of clean air wafting through my lungs like a long, cold drink of water, rivers without end that transform into vibrant oceans. I hold my ear to the shell of the past and present and listen to the voices that come through. In my galaxy of private epiphanies in Utah's mountains and deserts, I have found a way to create an interconnected mesh of my heritage and my fierce love of this planet, grounding and consolidating all my various identities into one based in empathy, kindness, and connectedness—teachings I have found time and time again in the Quran. I tuck away the book and find sleep under a gnarled lattice of pines that goes on and on among the unknown reefs of eternity.

This article appeared in the May/June 2018 edition with the headline "The Quran in My Backpack."

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club