How Is the Netherlands Preparing for Sea Level Rise?

Floodable parks, salty lettuce, and other tools for a soggy planet

As sea levels rise, people with expertise in keeping water at bay are going to become very popular. Many of them will likely be Dutch. The Netherlands has been constructing flood barriers for centuries and added a massive network of dams and levees after a 1953 flood killed 1,835 people. Twenty-six percent of the country is below sea level. Schoolchildren are taught how to swim with their clothes and shoes on to prepare them for floods.

Hundreds of years of trial and error, plus a nationwide acknowledgment that climate change is a very real thing, have put the Dutch ahead of the curve when it comes to planning for encroaching waters. Here are a few of their innovations.

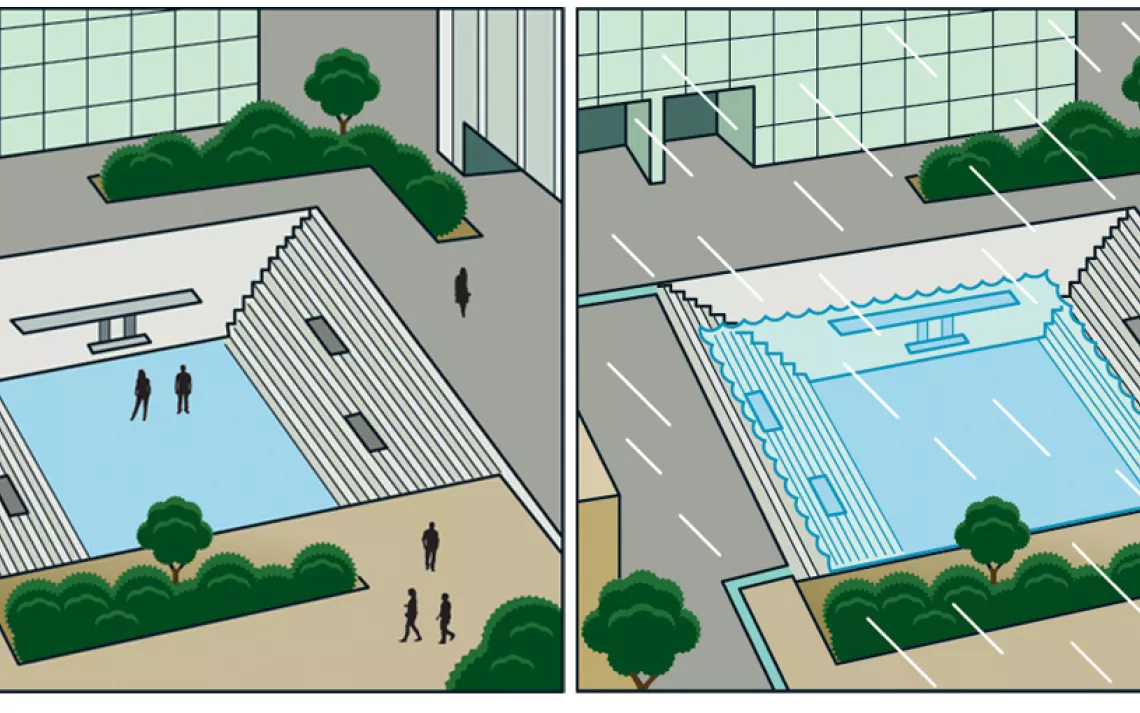

The Water Square

Imagine a standard European plaza where people meet to chat, drink coffee, read the paper, play chess—all your classic plaza activities. Now imagine it nestled snugly in a giant concrete soup bowl. Water Square Benthemplein in Rotterdam was built with floodable amenities like stone benches. When rains come, gutters set into the sidewalks carry water away from nearby buildings and into the plaza, turning it into a temporary reservoir.

Salt-Tolerant Crops

Dutch farmland is already experiencing saltwater intrusion—and as seas rise, more saltwater will seep into coastal farmland around the world. Some farmers are switching to crops like samphire, a now-trendy sea vegetable once known as "the poor man's asparagus." On Texel Island, scientists and farmers are breeding crops that can grow in salty conditions with relatively low loss of yield. Their greatest success so far is a potato four times more salt tolerant than standard varieties. One customer for this technology is Pakistan, which is planting test plots where the rising Arabian Sea is changing the ecology of the Indus River Delta.

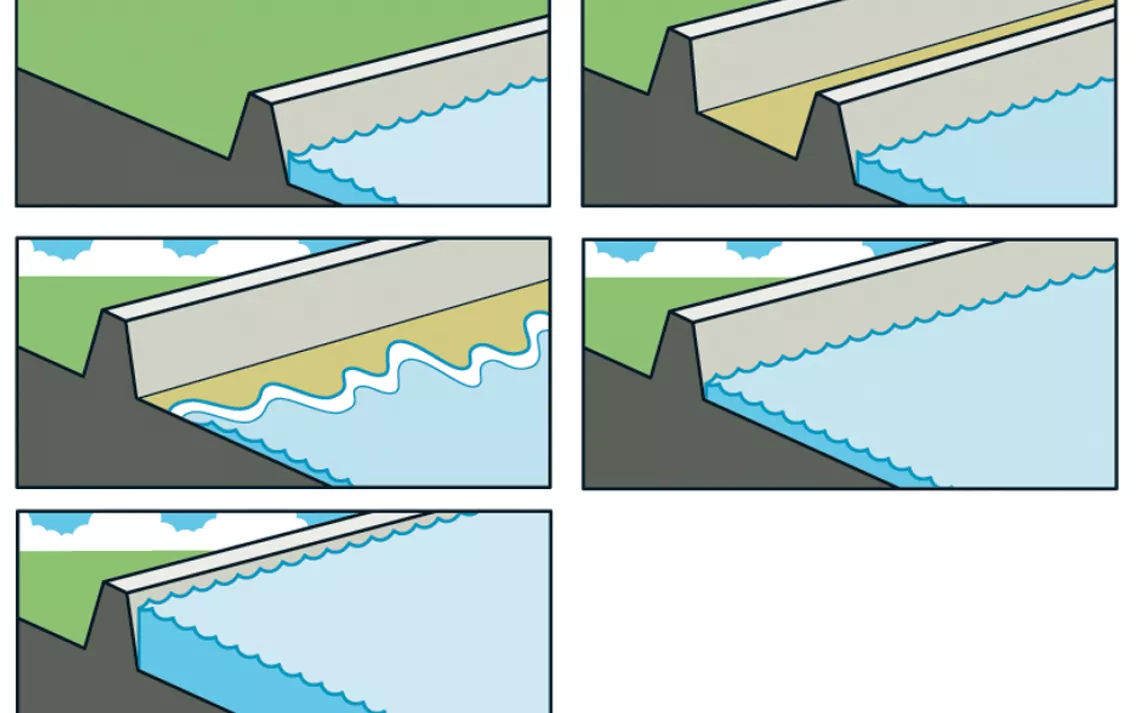

The Sand Engine

The Dutch were dredging sand off the Delfland coast every five years to replenish beaches that were protecting the area from storm surges. Then a professor at Delft University of Technology thought, Why not use dredged sand to create a giant sandbar in a location that would let wind and waves gradually redistribute the sand along the shoreline? The coastline could be protected for 20 years, and less-frequent dredging might mean less harm to local wildlife. Seven years in, sandbars are in the works along the Netherlands coast and in the United Kingdom.

Letting the Water In

Hundreds of years' worth of flood infrastructure in the Netherlands held back the water but also dried out the peatlands near the coast, causing them to compress and sink below sea level. In the 1990s, the government began removing and lowering dikes (a process known as "depoldering") and relocating farmers to higher ground so that the land around them could safely flood again. The Netherlands still has no shortage of high-tech flood barriers, but this approach is a reminder that sometimes adaptation means retreat.

This article appeared in the January/February 2019 edition with the headline "Water World."

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club