Fahrenheit > Celsius

Can we talk about global warming in a language Americans understand?

Photo by cvoogt/iStock

For the better part of 20 years, environmental policy wonks, activists, journalists, and academics have debated, sometimes acriminously, how best to communicate the existential danger of dismantling Earth’s once stable climate. Should we frame climate change as a hopeful opportunity to address other social ills, or are we best served speaking in fearsome language about how truly awful the changes to Earth could be? Maybe climate change should be couched in the language of past accomplishments—the wartime mobilization of World War II or the inspiring activism of the women’s suffrage and civil rights movements. Or maybe we should dwell on the dangers of the problem. Perhaps it’s just a matter of using stronger language; in May, The Guardian released a new style guide for its writers that encouraged using more urgent terms like “climate crisis” and “global heating.”

While I’ve got some opinions of my own, I mostly lean toward an all-of-the-above strategy: Use whatever global warming/global heating, climate change/climate crisis language you think will work best, depending upon whom you’re talking to. Call it “situational rhetoric.”

I do, however, have one modest proposal to make. We should stop talking about rising global temperatures in Celsius and use the measurement that Americans understand best: the Fahrenheit scale.

Since the vast majority of the world measures temperatures in Celsius, and since Celsius is the default measurement for scientists, most climate change communication takes place using the 1-to-100 scale. But for the 325 million people in the United States, Celsius is the equivalent of Latin. It means nothing to Americans.

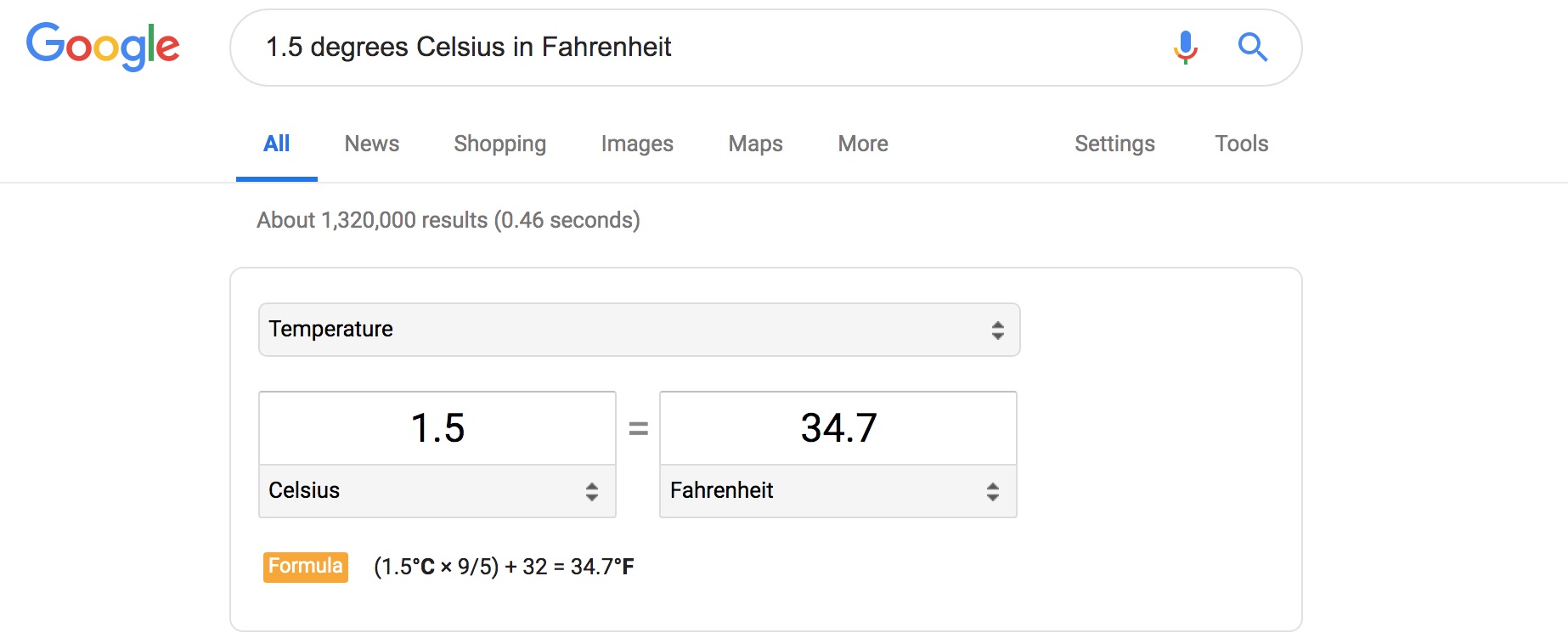

A quick Google search reveals the challenge of talking about climate change in Celsius. Imagine a climate science neophyte who wants to better understand the goals outlined in the Paris Agreement and who types “1.5 degrees Celsius in Fahrenheit” into the search engine. Here’s what they’d get:

Thirty-four degrees? Sounds cold. Even worse, seems confusing.

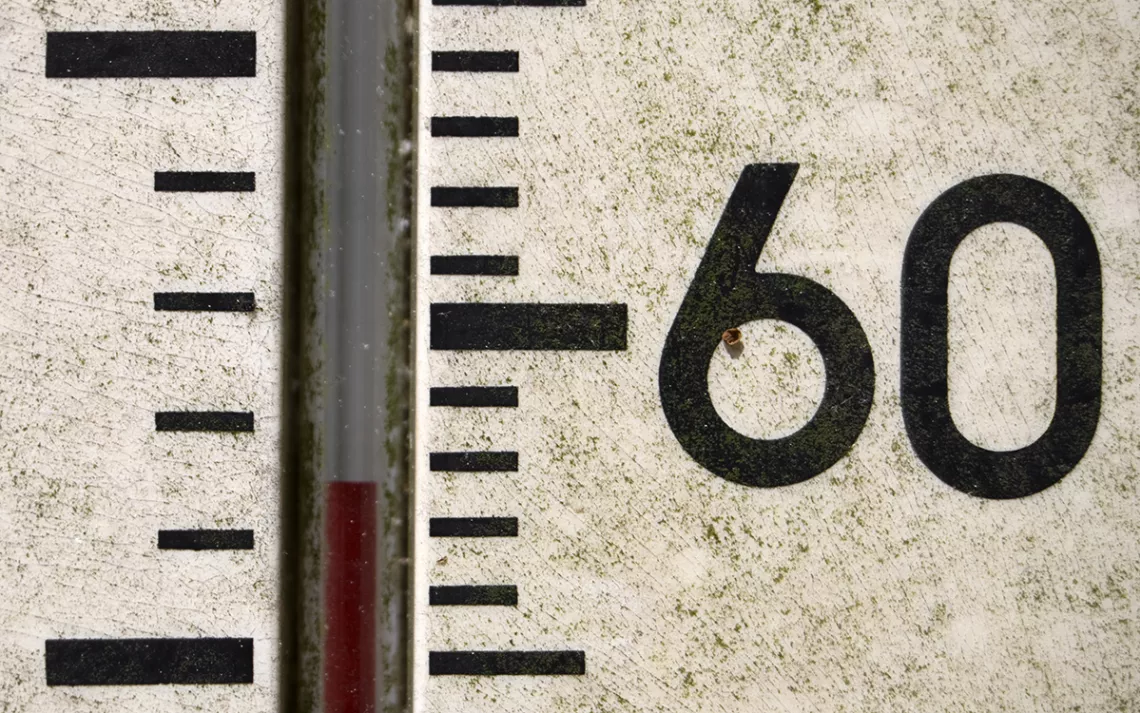

For most Americans, the metric system, and the Celsius scale in particular, is baffling. (I mean, why is a kilogram greater than a pound but a kilometer is shorter than a mile?) Temperature measurements in Celsius are meaningless. A 40°C day in Barcelona is sweltering; a 40°F day in Baltimore is frigid.

The problem with discussing climate change in Celsius is that it understates the scale and intensity of the climate threat. A 1.5° or 2°C increase in average global temperatures simply doesn’t sound like much to Americans.

Imagine if we were to consistently talk about climate change in Fahrenheit. One degree of Celsius is the equivalent to 1.8 degrees Fahrenheit. Do the math: 1.5°C becomes a 2.7°F rise in average global temperatures; a 2°C rise is the equivalent of a 3.6°F rise.

I suspect (and I admit this is little more than supposition) that numbers like 2.7 and 3.6 will still sound modest to many people. But I think the situation changes as the conversation turns to the most worrisome climate change scenarios.

Even if every country meets it obligations under the Paris Agreement, we’re on track to hit 3°C of global warming by the end of the century, according to the number crunchers at Climate Action Tracker. Now we’re talking about 5.4°F—the difference between a lovely spring day and a warm one. In the absence of meaningful action—a terrifying though realistic scenario given that greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise—we could be on track for as much as 4.4°C of warming by 2100. That’s nearly 8°F—the difference between a warm day and an uncomfortably hot one. Eight degrees is the spread between the average August high temperature in Kansas City and the average August high temperature in Minneapolis, more than 400 miles to the north. It’s a big deal.

In short, to talk about global warming in Fahrenheit doesn’t just make the climate conversation more intelligible to more people. It makes the conversation visceral. Discussing global warming—or global heating, if you prefer—in Fahrenheit converts abstract scientific measurements into actual lived experiences. Fahrenheit is how Americans know the weather, how they feel it on their skin. If we want people to really get the direness of the climate crisis, we need to hit them where they feel, not simply where they think.

Some climate communicators are already doing this. The good folks at InsideClimate News and Vox often (though not always) give readers figures in both Celsius and Fahrenheit. The only problem is that usually the more colloquial measurement of Fahrenheit is relegated to a parenthetical. The presumptions of understanding are backward. Fahrenheit should come first in order to connect with the greatest number of readers, and then Celsius second, to satisfy the science nerds and wonks among us.

So, all you journalists and activists and public-facing scientists, let’s get together and keep in mind this simple formula for mainstream climate change communication: F > C. It’s a small thing, but who knows—it might just have a large impact. If we can do a little bit better at speaking in plain English measurements, we’ve got a better chance at avoiding those worst-case scenarios.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club