The Photo Ark Charts a Course Across Airwaves

Photographer Joel Sartore talks about tomorrow’s PBS premiere of RARE

Sartore is surrounded by his images from the Photo Ark at the National Geographic Museum in Washington, D.C. | Photo courtesy of National Geographic

Veteran National Geographic photographer Joel Sartore may well have perfected the art of appealing to people’s inner conservationist. Since 2005, the real-life Noah has been on a quest to get each of the world’s 12,000 captive species, especially those at risk of extinction, on board his Photo Ark—a digital photo collection and one of the most comprehensive records of the world’s biodiversity. Each member of the Ark undergoes a formal studio shoot, set against plain white or black backgrounds. This up-close approach not only renders mole rats and mice every bit as magnificent as pangolins and pandas, but also gets people to look animals in the eye, to identify with the creatures, and to think harder about the ways in which our actions help or hurt them.

Sartore’s photos have prompted South American governments to protect their parrots and Australians to aid their koalas. In the United States, the Photo Ark has helped restore populations of Florida grasshopper sparrows and Salt Creek tiger beetles. But of course, saving the world’s wildlife from the deluge of climate change, deforestation, habitat loss, invasive species, pollution, and human development is going to take longer than 40 days and 40 nights. Already, Sartore has traveled to 40 countries and to date netted about 6,400 species—including 576 amphibians, 1,839 birds, 716 fish, 1,123 invertebrates, 896 mammals, and 1,245 reptiles. He estimates he has at least 15 years to go, noting that “now we have to travel further to get fewer animals.”

Sartore’s photos have prompted South American governments to protect their parrots and Australians to aid their koalas. In the United States, the Photo Ark has helped restore populations of Florida grasshopper sparrows and Salt Creek tiger beetles. But of course, saving the world’s wildlife from the deluge of climate change, deforestation, habitat loss, invasive species, pollution, and human development is going to take longer than 40 days and 40 nights. Already, Sartore has traveled to 40 countries and to date netted about 6,400 species—including 576 amphibians, 1,839 birds, 716 fish, 1,123 invertebrates, 896 mammals, and 1,245 reptiles. He estimates he has at least 15 years to go, noting that “now we have to travel further to get fewer animals.”

Starting tomorrow, viewers can tag along with him. Premiering on July 18 at 9/8c on PBS is RARE—Creatures of the Photo Ark. The three-part series, 18 months in the making, follows Sartore across the globe—to the zoos and nature preserves of Africa, Asia, Europe, North America, and Oceania—as he documents threatened species and explains surprising and important information about why ensuring their survival is so critical.

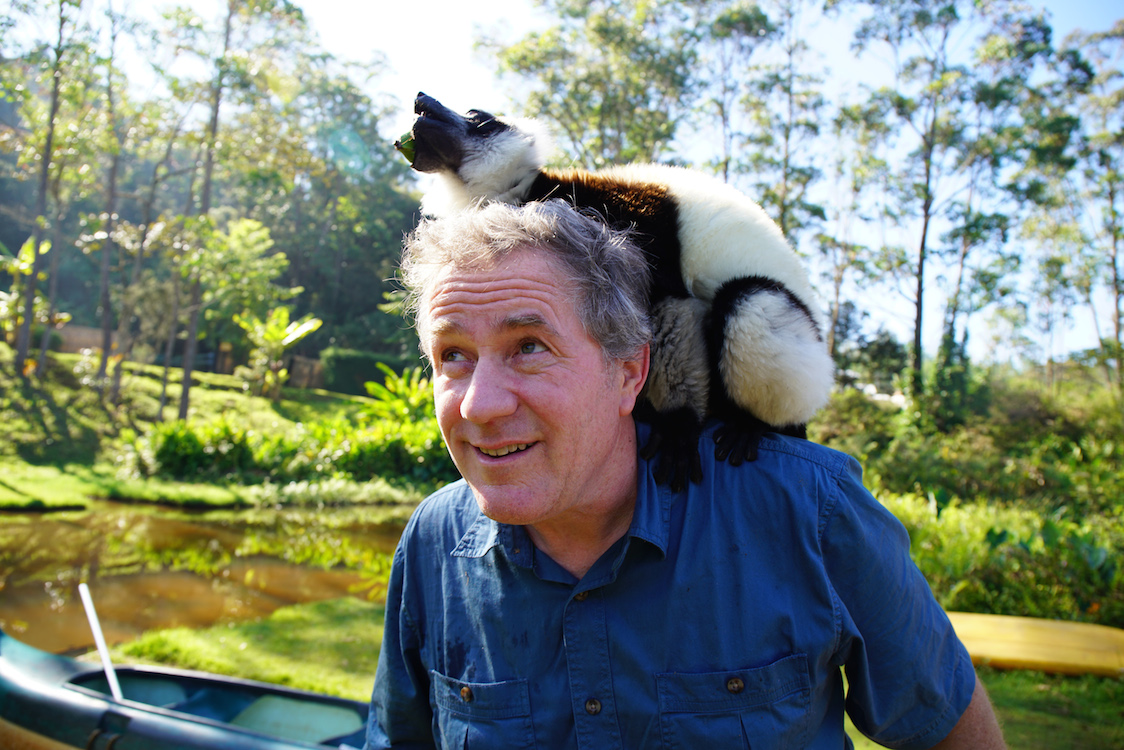

Viewers are made privy to the logistical and emotional efforts required to capture at-risk species. The race against time is rendered palpable as the intrepid yet folksy, quick-with-a-joke Sartore struggles to persuade a 500-pound tortoise to smile for the camera, plays with prankish, semihabituated lemurs, and heads into the mountainous rainforests of Cameroon alongside scientists working to save the rarest gorilla on Earth: the Cross River gorilla.

The show is unscripted and features Sartore, a natural storyteller, doing his work—setting up his backdrop and other equipment and crossing his fingers that his subjects will play along—in a seemingly natural state. Once back in the production studio, Sartore recorded voice-over lines, making him RARE’s plucky star as well as its knowledgeable narrator. “Fifty percent of all animals are threatened with extinction, and it’s folly to think we can drive half of everything else to extinction but that people will be just fine,” he cautions.

After vicariously traveling with Sartore to China to capture the Yangtze giant softshell turtle, to Spain for the Iberian lynx, and to New Zealand for the rowi kiwi (among many other places), Sierra tracked the ambitious photographer down by phone at his Lincoln, Nebraska, home. Sartore revealed what it was like to be on both sides of the camera, how he gets people to care about even the strangest and ugliest of creatures, and why zoos are in a position to save the animal kingdom.

After vicariously traveling with Sartore to China to capture the Yangtze giant softshell turtle, to Spain for the Iberian lynx, and to New Zealand for the rowi kiwi (among many other places), Sierra tracked the ambitious photographer down by phone at his Lincoln, Nebraska, home. Sartore revealed what it was like to be on both sides of the camera, how he gets people to care about even the strangest and ugliest of creatures, and why zoos are in a position to save the animal kingdom.

Sierra: There have been two Photo Ark books (2010’s Rare: Portraits of America’s Endangered Species and 2017’s The Photo Ark: One Man’s Quest to Document the World’s Animals), with a third, the tentatively titled Birds of the Photo Ark, slated to come out next year. Your project has also been featured extensively in National Geographic, Audubon, Sierra, and other national publications. Why a TV show, and why now?

Joel Sartore: Not only is the TV show a good way to let more people know about the Ark and get the public to care about extinction, but frankly it was also a good opportunity to get some extremely rare creatures aboard—ones that I normally wouldn’t have the funding for. The show allowed us to get to Madagascar, the Czech Republic, and to China—places I normally couldn’t even imagine visiting.

A critically endangered lemur (Decken's sifaka) in Madagascar | Photo by Joel Sartore

You spend a lot of time shooting in zoos, which can be controversial places among conservationists. What type of zoo environment is most beneficial, in your opinion, not only for the animals but in terms of educating visitors?

My feeling on zoos and captive breeders is that they’re really the keepers of the animal kingdom—often, they keep species going until their habitats can be restored. Many of the species I photograph exist only in captivity—they live in institutions where they receive abundant attention and care, and where they’re used to and love people. Well-run zoos are conservation centers—the focus is on habitat restoration, captive breeding, and poaching patrol. And they’re often the only places where urban people can see and touch and smell and see wildlife. I’m afraid we’re moving toward a world where we don’t have a connection to the wild, and won’t want to save it. Ours might be the last generation that’s connected to and cares about the animal kingdom—and zoos can help us save that. It’s really a matter of making sure the public understands that many zoos nowadays are places devoted to breeding and maintaining threatened animals.

A female Colombian red howler monkey | Photo by Joel Sartore

Many parts of the show are funny and upbeat, but the series kicks off with your visit to Dvur Kralove Zoo near Prague, where you record an elderly northern white rhino, who died shortly after your shoot, leaving only three of her kind in the world. How did RARE manage to strike that balance as a fun, yet also moving and at times sad, viewing experience?

I didn’t cut the film myself, but I know that a big mission was to show that [the Photo Ark] is about life and death—that it’s serious—but to also give people hope and inspire them with proof that we can all make a difference, and also to teach them about biodiversity. We introduce people to animals they’ve never seen before—they may have seen mountain gorillas and elephants, but probably not a Lower Keys marsh rabbit or a kakapo, the world’s only flightless parrot, which lives in New Zealand. We wanted to create a compelling story that wouldn’t be too depressing, and that would make people actually want to get up off the couch and save.

A monk saki at Cafam Zoo in Colombia | Photo by Joel Sartore

What’s your advice for getting people to care about a creature that’s important to ecosystems and perhaps even public health, but that isn’t photogenic or conventionally cute, like the blind, buck-toothed, hairless, and mysteriously cancer-resistant naked mole rat you recorded at the Saint Louis Zoo?

I ask myself this question all the time. Because getting someone to care about a mussel without eyes, or anemones or sea urchins—it’s a really tall order. I think the secret is to get them engaged in the tent of conversation by drawing them in with other species, or else with interesting facts about the not-so-cute animals, or the ones that may not have faces or eyes. Once you grab people with something interesting, they tend to realize that all wildlife is affected by how we live our lives—that pollinating insects drive ecosystems and bring us one-third of every bite we eat, and that healthy, intact rainforests also help regulate rainfall in places like Nebraska, where I live. That wildlife connection drives home the point that we have to have a healthy Earth to live—that we could go extinct, too—and that food doesn’t come from the grocery store. Sometimes the sea urchin or the naked mole rat can lead to discussions about big issues we need to think about.

A channel-billed toucan | Photo by Joel Sartore

What are you most proud of? Do you have a favorite conservation success story?

I don’t ever feel like anything is completely out of the woods, but with many species, the pictures helped. For instance, a few years ago the Florida grasshopper sparrow was slated to go extinct—there was no real attention or funding in place—and then an Ark photo ran on the cover of Audubon and the government ending up allocating real funds to start a captive-breeding program. But in terms of conservation wins, it’s not quite as easy as giving Photo Ark coverage and then seeing the animal saved. We certainly raise the profile for folks doing great work, but the fight is never really over—we’re cautious about victory.

A great Indian civet, shot at Taiping Zoo | Photo by Joel Sartore

What was the most rewarding experience of filming RARE?

Getting to the northern white rhino—the last one that was in an environment where we could light it—on her very last week. She was such a sweet animal, and clearly near the end of her life. She had a lot of cysts, and she’d been sleeping all the time. Because I’d wanted to get that species for many years, she was the most satisfying. But I’m just as excited about getting a sparrow as I am a tiger, because they all count. And the Photo Ark really lets everyone shine. It’s why animals are the same size on these black-and-white backgrounds—so even a mouse can look incredible.

What was the most difficult-to-photograph creature featured in RARE?

The South China tiger wasn’t terribly easy to shoot, and in terms of access, the Yangtze giant softshell turtle was difficult. But once we explain our project to zoos and institutions, they typically get on board. They get free pictures, and then we promote their story.

Sartore and some baby tigers | Photo courtesy of National Geographic

What would you suggest concerned viewers do to help protect endangered animals?

To get involved in conservation, you don’t need to reinvent the wheel. I’d start at your local zoo, most of which are really conservation centers nowadays—they can tell you what’s needed, whether it’s your money, or your volunteer time, or your efforts on social media. National Geographic and the Audubon Society, and the Nature Conservancy, and of course the Sierra Club have all been at this for a long time—they’re great resources for people wanting to learn how to do more. Just one visit to a local zoo or aquarium can result in huge efforts. People can always contact me through my website, too.

Do you have a favorite among the animals you’ve photographed?

My favorite one is always the next one. On Thursday, I’m going to a wildlife rehab center in Oklahoma, Wild Care, and then to the Oklahoma Zoo. This week I shot 18 varieties of wolf spiders in my living room. There’s a spider lady at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln studying wolf spiders, and she just brought them over.

Do you have any animals at home?

We have a goldendoodle and a rescue shih tzu. The dogs seemed pretty oblivious to the spiders.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club