How Blue Is Your Valley? Your Voice, Your Future: A Community Conference on Water in the San Joaquin Valley

held at Fresno City College on April 24, 2015 — a brief report by Robert Turner

Diverse water issues in the San Joaquin Valley were the subjects of a community conference held at Fresno City College by the Environmental Law Section of the State Bar of California on April 24, 2015. "How Blue Is Your Valley? Your Voice, Your Future" was highlighted with a lunchtime keynote address by California author and journalist Mark Arax, who is currently writing a nonfiction book on the tangle of water rights and other issues in the Central Valley. His discussion of the difficulty of researching water policy and its impact on the private lives of the various water stakeholders (who include us all) was both instructive and evocative, as he told tales of meeting farmers and fishermen, oilmen and dairy operators, rural homeowners and government managers, all with their own personal perspective on the current drought and how to manage this most precious of natural resources.

In one story, he fielded an angry complaint on a call-in radio program from a Los Angeles resident who resented having to cut short his showering time to allow a Central Valley farmer to grow "trail mix," by reminding the Los Angelean of how his city initially mismanaged their own local Los Angeles River before striking outward to prospect first the Owens River, then the Colorado, and eventually the waters of California's northern basins, while the almond farmer is merely trying to use his own local water resource. Arax dared to question whether certain regions in the Valley should ever have become farmland in the first place, as well as the absurdity of allowing water sales and trades in order to build new residential communities. His expansive vision — both outward and inward, as well as back to the beginning of colonization in California — added a needed breadth of perspective to the numerous politically complex and thorny regulatory issues surrounding the use and management of water in the Central Valley.

Panel Discussions

The four panel discussions during the daylong event were illustrated by slides and PowerPoint notes that are available here as viewable and downloadable .pdf files. Click on the titles below to access these presentation files.

Valley Fever: Drought Resilience in a Warmer San Joaquin Region

I Feel the Earth Move Under My Feet: Subsidence, Sustainable Management, and California's New Groundwater Law

The Human Right to Water: Providing Safe Drinking Water for Disadvantaged Communities

Fracking in the San Joaquin Valley: What Does It Mean to You and Your Water Supply?

A Dam at Temperance Flat Will Be Costly in Taxpayer Funds and Environmental Consequences

by Robert Turner [This article first appeared in the January-March 2015 issue of Tehipite Topics] posted on March 13, 2015

How Proposition 1 Funds Will Be Spent

The passage of Proposition 1 (The Water Quality, Supply, and Infrastructure Improvement Act of 2014) in the November election allocated 7.12 billion dollars to state water supply infrastructure projects, such as public water system improvements, surface and groundwater storage, drinking water protection, water recycling and advanced water treatment technology, water supply management and conveyance, wastewater treatment, drought relief, emergency water supplies, and ecosystem and watershed protection and restoration. Of this total a half billion will be used to improve water quality (including drinking water in disadvantaged communities), 1.5 billion will be granted for ecosystem and watershed protection and restoration projects, 0.8 billion to the creation of integrated regional water management plans, 0.7 billion for water recycling and developing advanced water treatment technologies, 0.9 billion to cleaning up groundwater contamination, 0.4 billion for flood management projects, and by far the largest slice of the pie, 2.7 billion dollars toward new water storage facilities across the state, i.e., new dams and reservoirs.

The state budget process will be used to determine how funds in a particular category are allocated. The exception to this is with that last chunk of money benefitting water storage facilities, which will be put into a competitive process. The Legislature will not oversee them or impose conditions through the budget process. Instead, these funds will be allocated directly by the California Water Commission (CWC), which is inviting public participation in developing the regulations to define and guide the process of deciding where these funds will go. None of the funding from Proposition 1 can be used to build a canal or tunnel to move water around the Delta.

Three New Dam Projects Proposed

The CWC has been in existence for several decades but without much power to do anything in recent years. Suddenly invested with new duties and control over massive funds, the Commission will be hit with competing proposals to accomplish the goals of the new law. At least three dam projects are under consideration: the raising of Shasta Dam to enlarge the reservoir’s capacity, the construction of the Sites Offstream Storage Reservoir north of Sacramento, and the construction of Temperance Flat Dam in the upper reaches of Millerton Lake inside the San Joaquin River Gorge. Any project that is accepted for Proposition 1 funding must meet the requirement that these funds be dedicated toward “public benefits,” which include restoring habitats, improving water quality, reducing damage from floods, responding to emergencies, and improving recreation. Remaining project costs must be met by local governments and other entities.

The proposed Temperance Flat Dam is estimated to cost 2.5 billion dollars by the Bureau of Reclamation (BoR), while other estimates range as high as 3.3 billion. The Bureau is claiming that half of the dam’s cost will be to the public benefit in the form of increased salmon production downstream of the dam, so those funds can be requested from state taxpayers through the bond. Friends of the River, however, states that the BoR’s own estimates of salmon population improvements are a paltry 0.4 to 2.8%, depending on how the dam is operated. Two of the dam’s five operation scenarios actually reduce salmon populations by upwards of 13%. Whether the CWC considers that of adequate public benefit is by no means certain. Should any funds at all be allocated by the CWC toward the Temperance Flat Dam project, clearly whatever the CWC provides will have to be more than matched with funding from other sources.

Factoring in the river’s average annual yield, it turns out that building a dam at Temperance Flat will double the debt of the Central Valley Project, while increasing available water by merely one percent of current levels. Water from Temperance Flat will be the most expensive in the state, its cost ultimately borne by the public in one form or another through debt, fees, and taxation.

Reservoir Capacity versus Annual Yield

To many of us the building of Temperance Flat Dam is not a done deal. Proponents tell the media and public the dam will increase storage capacity in the state by over 1.2 million acre-feet (a net increase due to an overlap with the upper reaches of existing Millerton Lake), generating confusion that this amount will soon be available for use. The key figure to keep in mind is not reservoir capacity but average yield on the river. Based on known San Joaquin River hydrology, 70,000 acre-feet is the modeled average new yield of water per year. At that rate it would take decades to fill the reservoir even if the water were only stored and never used. Dam proponents have given the wrong numbers to the public, confusing storage with yield, so that people are expecting large quantities of water to be available with this new dam. Once these physical and financial realities set in during the oncoming debate, a discerning public may turn against construction of the Temperance Flat Dam.

Where’s the Water to Fill Temperance Flat?

Most of the water brought down from the mountains by the San Joaquin is already being held in Millerton Lake. Temperance Flat Dam would be 665 in height, making it the second-highest dam in California (and fifth in the nation). If it ever could be filled, it would drown miles of wild river within a BLM Conservation Area that includes a long stretch of whitewater, beautiful flood erosional features, a rare granite cave of extraordinary aesthetic value, and a site deemed sacred to local tribes by the Native American Heritage Commission.

The proposed reservoir that would be formed behind the dam is large enough to hold the entire amount of water gathered in a year within the San Joaquin River basin. But it is unreasonable to think the reservoir could be filled anytime soon, if ever. The dam would do little to increase the annual yield from the river basin. Less than 100,000 acre-feet of water per year would be added in storage, and with looming mega-droughts on the horizon, that number may be reduced to zero in the coming decades.

It should be remembered that most of the water that enters the smaller Millerton Lake today does not stay stored there for long. It is quickly dispensed into canals and downstream for agricultural use across the San Joaquin Valley. With San Joaquin River water rights today over-allocated by eight times the river’s average annual yield, one wonders whether the Bureau of Reclamation has the right to capture any water at all behind the Temperance Flat Dam.

Bad News for Millerton as a Recreational Park

Some say that the Temperance Flat reservoir will become the main storage facility to the detriment of Millerton, requiring recreational boaters, swimmers, and fishermen to transfer their activities to more remote parking areas farther away from the city, increasing travel time and adding more gasoline-burning pollution to our valley air. While it seems counterproductive not to keep Millerton Lake full during flush summers, while the upper reservoir is allowed to rise and fall, perhaps the reverse is necessary in order for proposed electrical generating tunnels to function effectively. With two reservoirs at different elevations so close together, they could function like Wishon and Courtright Reservoirs as an enormous rechargeable hydroelectric battery, generating electricity during peak times when it is more valuable, then buying it back more cheaply off the grid in the off hours to pump water back uphill to the upper lake. Finally, the construction of Temperance Flat Dam would do nothing to mitigate the collapse of groundwater aquifers in the southern Central Valley. Better than capturing flood waters in a wild and scenic gorge would be to channel the water into shallow filtration basins to allow for groundwater recharge. Building another large storage facility in the mountains would increase water loss by evaporation.

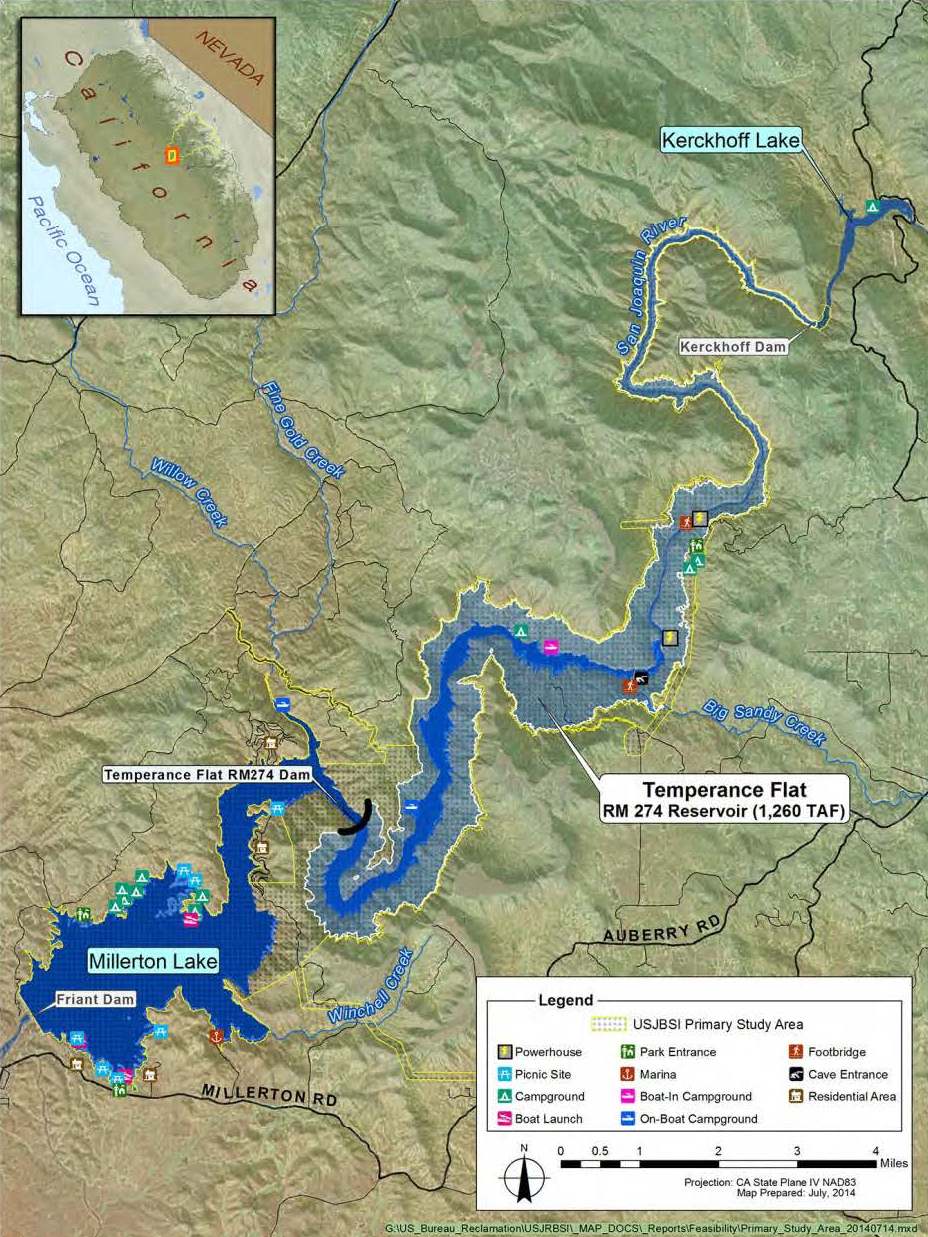

Map of the Proposed Temperance Flat Dam and Reservoir

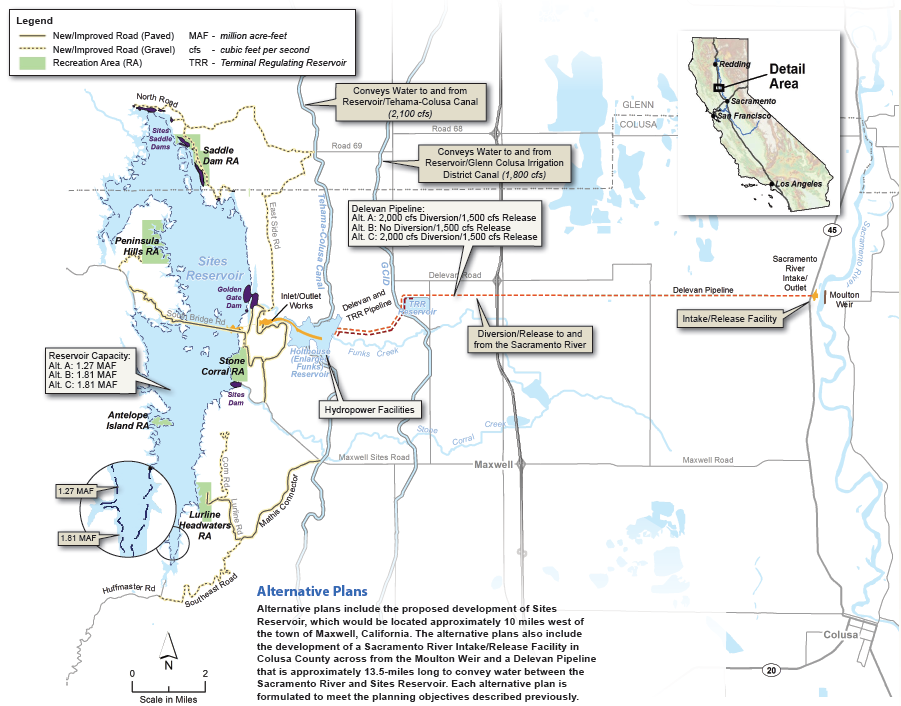

Map of the Proposed Sites Reservoir Project

Historic New Laws Finally Establish Groundwater Regulation in California

by Robert Turner [This article first appeared in the January-March 2015 issue of Tehipite Topics] posted on March 13, 2015

Groundwater Management Will Be Local, Not Statewide

“We have to learn to manage wisely water, energy, land, and our investments,” stated Governor Brown as he signed three bills last September that create the framework for sustainable, local groundwater management for the first time in California history. The legislation, comprising AB 1739, SB 1168, and SB 1319, requires the establishment of local agencies to create sustainable groundwater plans tailored to their regional economic and environmental needs.

With the new groundwater regulations, governing authority will be local and regional rather than statewide. Groundwater basins will be defined as those described in the latest (2003) incarnation of the Bulletin 118 series from the California Department of Water Resources (DWR), a report to the Legislature that has been updated several times since the original assessment of groundwater basins authored in 1952. Fresno lies at the boundary between two of California’s ten hydrological regions, the San Joaquin River region north of the river and the Tulare Lake region to the south.

The “San Joaquin River Basin” is subdivided (from north to south) into Cosumnes, Eastern San Joaquin, Modesto, Turlock, Merced, Chowchilla, and Madera sub-basins on the east side and Tracy and Delta-Mendota sub-basins on the west side. South of the San Joaquin River, in the Tulare Lake Hydrologic Region, the “San Joaquin Valley Basin” is divided into seven significant valley floor sub-basins: Kings, Kaweah, Tule, and Kern County on the east side, and Westside, Pleasant Valley, and Tulare Lake on the west side.

Overdrafted Basins Must Develop a Plan by 2020

The geographical delineation of each basin or sub-basin will be the legal boundary for that basin’s groundwater authority, known as a groundwater sustainability agency. These agencies will be created and composed according to representation by all government water authorities who share area designation within a basin’s geographical extent as defined by the latest Report 118 (including future amendments subsequent to the current 2003 update). A groundwater sustainability agency has two years to constitute itself and, if the basin is seriously overdrafted, five years in which to write a plan for sustainable use and allotment of groundwater within the basin. Every San Joaquin Valley basin from Chowchilla south to Kern County is on the critical overdraft list. Other high and medium priority basins have until 2022 to begin management of groundwater resources. By 2040, all of these critical basins must achieve sustainability.

In developing a plan, the agency must consider the interests of all beneficial uses and users, including agricultural users, public water systems (large and small), municipal well operators, domestic well owners, local land use planning agencies, environmental users, disadvantaged communities, Native American tribes, and managers of military and other federal lands. Non-governmental groups can have a seat at the table as interested parties, but they will have no vote in the development of rules and allocations. However, a regular attendance by groups like the San Joaquin River Trust, Friends of the River, the Sierra Club, and the Audubon Society, may guarantee that their representatives have seats on committees that report to the main boards, and so it behooves each interested party to get and stay involved in these new agencies that are about to be formed.

GSAs Will Have Considerable Management Powers

The new groundwater sustainability agencies will be vested with considerable powers. They are authorized by law to adopt rules, regulations, ordinances, and resolutions, to conduct investigations of water rights, to require well operators to register wells and to measure and report extractions, to regulate extractions (including limiting or prohibiting groundwater production), to impose fees and assessments, to impose well spacing requirements, to undertake enforcement actions for noncompliance, and to acquire property and water rights. Counties will maintain their well permitting authority, although the GSAs can request that the counties provide well construction applications for their consideration and comment.

The new groundwater laws do not require metering or regulating anyone drawing out less than 2½ acre-feet per year, which covers most homeowners currently getting their household or landscaping water from wells. Also exempt are several areas of Southern California that are being adjudicated and have a water master appointed by the court. Basins that are fairly flush with water will be completely free of oversight.

However, over the long term, it may be prudent to have all the districts develop plans, so that hard data on groundwater usage can be collected everywhere for accurate statewide planning, as well as to prevent these non-priority basins degrading and getting added to the critical list. The DWR needs local input from every part of the state. The National Forest Service can be of assistance in assessing the overall state of water in California, since they are required to do a water budget for the areas under their jurisdiction.

The aim of the new management process is to attain sustainability, which means no chronic lowering of groundwater levels or unreasonable reduction of storage, no significant seawater intrusion, no continued degradation of water quality, including migration of contaminant plumes that impair water supplies, no significant land subsidence interfering with surface activity, and no surface water depletions that have adverse impacts on their beneficial use. To this end, local land use planning agencies must refer any proposed adoption of, or amendment to, a general plan to the local GSA for review. The GSA will then provide local planning agencies with the anticipated effects on the groundwater resources.

All Users Will Likely Be Losers

The new laws will have no direct effect on a landowner’s surface water rights, and with regard to allocation of groundwater resources, there will be priority for senior water rights holders, who will not be required to incur a significant expense for the benefit of lower-priority rights holders. No water users will get to increase their current use levels. Instead there will be losers, worse losers, and really big losers, as there just isn’t enough subsurface water to go around while still allowing for groundwater aquifer replenishment. Many users will have to accept drastic reductions in their current levels of use.