For an Antidote to Climate Despair, Look to the Impact of Rachel Carson’s "Silent Spring"

Here's what the storied writer has to teach us

A field of marsh marigolds and blue toadflax in a rural area on the eastern shore of Maryland on a brilliant May morning. | Photo by Joesboy/iStock

Did you hear the birds singing outside this morning? A lot of us take that common sound of nature for granted. Most people these days do not realize how close we came to living in a much quieter world, to the widespread destruction of entire ecosystems and some of our most iconic species.

That our springtime is not silent today is thanks to one of the original victories of the modern environmental movement—and the book that many credit for starting that movement. It is a story of hope. One that should inspire faith in those of us who care deeply about stopping the climate crisis and saving our planet.

The synthetic pesticide dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane—commonly known as DDT— came into heavy use in the 1940s. It was used in crop and livestock production, in people’s home gardens, and to combat some insect-borne illnesses. Within a couple decades, it became clear that DDT made people and animals sick. It also sent certain species, like North America’s great birds of prey, spiraling toward extinction.

Then in 1962, the book Silent Spring by author and marine biologist Rachel Carson used science to expose the “shadow of death” cast by DDT. More than 40 years before former vice president Al Gore sounded the alarm about global warming with his film An Inconvenient Truth, Rachel Carson focused the world’s attention on the vast harm caused by humans’ indiscriminate use of chemicals to tame nature.

The New Yorker magazine first ran excerpts of Silent Spring in June of 1962. When the full book was released the following September, it took only three months to sell 100,000 hardcover copies and two years to sell more than a million. It ignited a movement. Within a decade, Congress passed the landmark National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was created. In 1972, DDT was banned, and one year later, Congress passed the Endangered Species Act.

That is just the beginning of the success story.

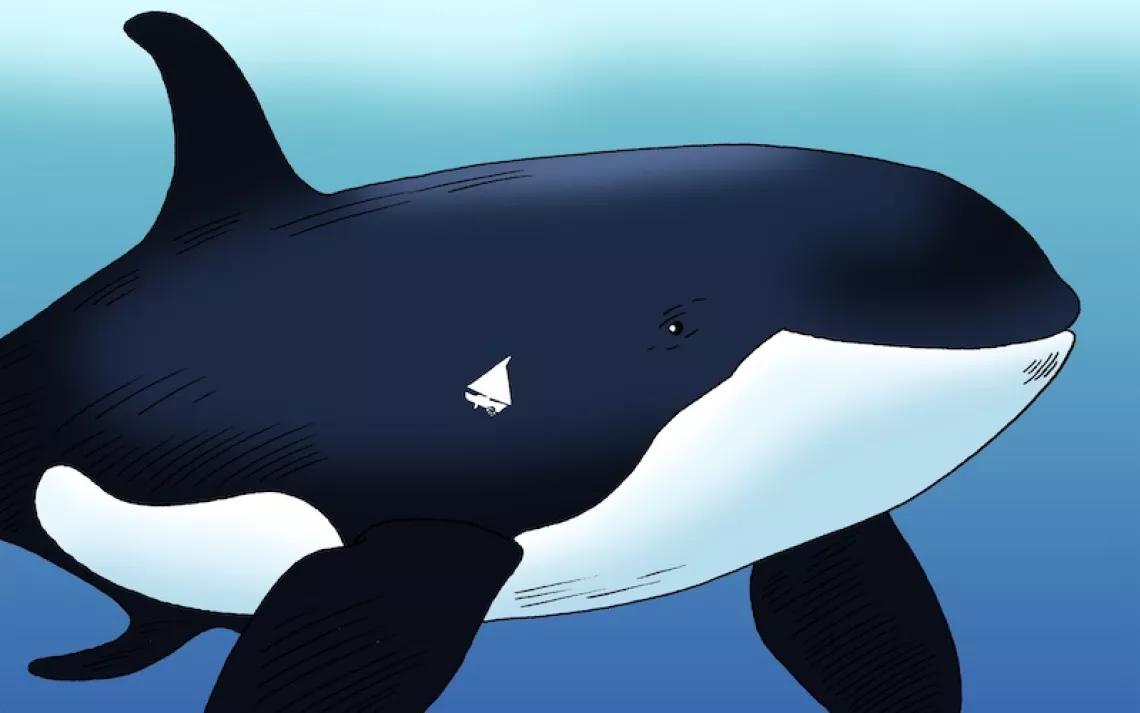

DDT did not just kill crop-killing bugs. It clung strongly to soil and ended up in the water. It remained toxic as it was passed from animal to animal all the way up the food chain. It became heavily present in the fish, rodents, and smaller birds eaten by eagles, hawks, osprey, condors, and the other great raptors. Then the raptors started to disappear. DDT poisoning caused the shells of the birds’ eggs to become so thin they broke under the weight of birds sitting on them in the nest. Between ending the use of DDT and the efforts to protect habitats and reintroduce animal populations, America’s great raptors came back from the brink.

The peregrine falcon, which has the distinction of being the world’s fastest animal, was close to being completely wiped out. By 1951, the last breeding pair of peregrines was documented in Illinois. Today, they are plentiful in the state, including its biggest city, Chicago, where the skyscrapers mimic the peregrines’ natural habitat among high cliffs. In fact, this year marks 25 years since Chicagoans voted the peregrine falcon the official city bird of Chicago. The Chicago Ornithological Society celebrated by declaring 2024 "The Year of the Peregrine Falcon."

Our national symbol itself, the bald eagle, was down to only 417 nesting pairs in known existence by 1963. Now, where I live in Maryland, I see at least one bald eagle almost every day.

Also in Maryland, in the same town where I am raising my kids, is the house where Rachel Carson wrote Silent Spring. The Rachel Carson House is nestled in a wooded neighborhood. It was designed by Carson along with a local builder, with large picture windows perfect for letting in light and observing the area’s wildlife. It is also the headquarters of the Rachel Carson Landmark Alliance.

The president of the alliance, Dr. Diana Post, says, “Protecting wild spaces, that was Rachel’s dream.” That dream is in action on Carson’s former property. And Dr. Post points out there are many examples of how people today continue to reach for that same dream, like the Biden administration’s “America the Beautiful: 30 by 30” initiative. That initiative aims to “connect and conserve” at least 30 percent of lands and waters by the year 2030.

In addition to Carson’s mark on protecting nature and public health, we must also recognize a lesson from Silent Spring’s impact: that, in the fight to save our planet, we can—and, I believe, we will—win. That is an important lesson for these times.

According to a study last year by the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication, around 7 percent of Americans are experiencing psychological distress over climate change. For the younger generations—Gen Zers and millennials—that number goes up to 10 percent.

Climate anxiety and despair are understandable. But while last year was the hottest year on record and severe weather events are increasing, cause of hope is all around us. Solar and wind power are now less expensive than dirty fossil fuels and getting more affordable by the day. And a new green manufacturing sector is taking root that is creating good jobs and will help the lives of working people, in addition to protecting our health and our environment. The movement launched by Silent Spring and our success in bringing back species that were all but extinct prove we are capable of great things. So, as we celebrate what would be Rachel Carson’s 117th birthday, let the fact that today our spring is not silent be a reminder that we can be our own salvation.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club