Slash and Burn

Why is the BLM clearing vast swaths of piñon-juniper forests across the West?

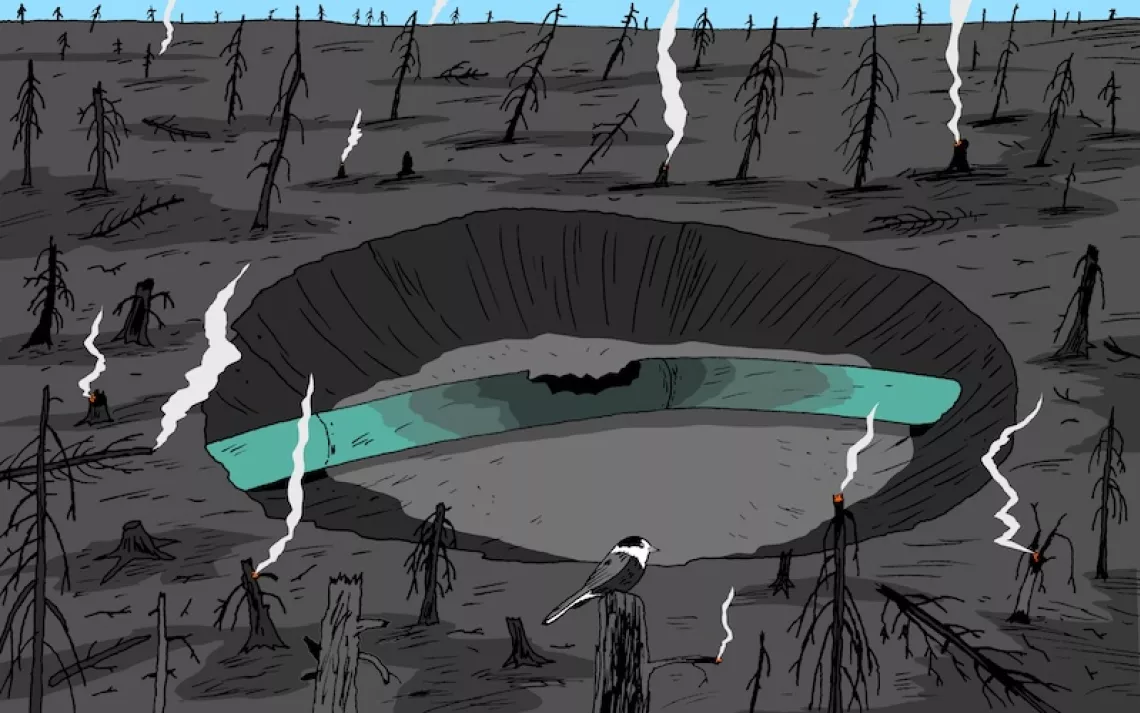

A logged and burned former piñon-juniper forest in Idaho, the result of a government tree-clearing policy. | Photo by Chad Case

ON A RAINY FALL DAY, Katie Fite climbed over fallen timber in a small ravine in the remote Stinkingwater Range, an escarpment rising to around 6,000 feet in Oregon's vast, flat Harney Basin. Her dogs, Bell and Zeke, zigzagged in front of her, tracing a faint trail into the deepening rift. This little defile is beautiful if unremarkable, one of thousands of small canyons that from overhead look like branching limbs inscribed into the lonely plateau country of east-central Oregon.

Fite reached out to touch a patch of neon-yellow moss stippling the bark of a towering juniper. The tree bore little resemblance to the stunted shrubs that adorn suburban front yards. This specimen was easily 60 feet tall, its limbs covered with a profusion of bluish berries. "Junipers grow only a few inches per year," she said. "This tree is hundreds of years old."

Then, the sylvan scenery abruptly shifted. We emerged from the forest onto a clearcut hillside. All the way to the valley floor, the ground was littered with downed logs and charred stumps. Twenty years ago, the Bureau of Land Management cut down many of the juniper trees on this 1,300-acre parcel. The junipers were not harvested for timber but left to rot where they fell. In 2007, the trees were burned, leaving piles of blackened limbs. Other trees were engulfed in flames while still standing. Their remains took on human-like forms: one a dancer in a bent-back pose, another a set of knotted arms with hands raised to the sky. Underfoot, mats of invasive medusahead and cheatgrass grew in an unbroken beige carpet.

Fite is the public lands director of the Idaho-based WildLands Defense. For three decades, the diminutive 65-year-old has been a gadfly in the arid lands of the West, documenting the destruction of their remote and largely uncelebrated native forests. She gestured to the hundreds of hoofprints in the wet ground. Though we saw no cows (presumably they'd been moved to a lower elevation in anticipation of snow), evidence of their presence was everywhere. The hillside had been pounded into a morass of weeds, mud, and char, and there was no shortage of dung on the ground. A half mile or so ahead, according to the map, flowed Crane Creek. But when we arrived, what we found was not a creek but a stinking mire, its banks littered with cow shit. Green pom-poms of algae swayed in the current. This rivulet, Fite explained, was once broad and deep enough to sustain a population of threatened Columbia River redband trout. No more. Grazing cattle had smashed the bed of the creek and reduced the waterway to a trickle.

Katie Fite of WildLands Defense has spent years documenting the destruction of piñon-juniper forests across the West. | Photo by Chad Chase

Overhead, a flock of drab gray Townsend's solitaires flitted past and landed in a towering juniper surrounded by stumps and piles of slash. These birds, like dozens of other species, depend on the late-season bounty of juniper berries. Under the tree's sprawling canopy, the ground was trampled and covered with manure. The juniper's low-hanging branches were chewed to woody ribbons. "The range managers hate these trees, but the cows clearly like them," Fite said. "Do you see any other place around here for shade?"

She summed up the damage: "Junipers can live for more than a thousand years, but the BLM says they are suddenly advancing. It's nonsense. The real reason for this deforestation is simple. It's to make room for cows."

THE SCENE ON CRANE CREEK has been repeated time and again across the American West. For decades, using terms such as "invasion" and "encroachment," federal and state land-management agencies have painted a picture of juniper and piñon pine as kudzu-like weeds devouring vast tracts of the West. One 2008 report by a researcher from the US Forest Service stated that "rapid expansion of piñon and juniper is well known to those who observe the land" and that "juniper has increased over tenfold since the mid to late 1800s, occupying roughly 7.5 million acres." The supposed Ent-like march of the trees has fostered, in some land managers, an outlook verging on disdain. "There isn't a natural resource professional in Baker County who doesn't want to get juniper out of sagebrush habitat," declared a 2011 newsletter from the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. "It degrades wildlife habitat, hogs water, and creates a wildfire hazard."

In response to this alleged ecological threat, federal agencies have undertaken a vast deforestation campaign across the West. Between 1940 and 1964, more than 3 million acres of piñon and juniper forests were cut down and converted to pasturelands, according to one estimate. (The totals are almost surely higher; before the passage of the National Environmental Policy Act in 1970, record keeping on such tree clearances was scant.) The BLM reports that nearly 600,000 acres of coniferous forests were eliminated between 2009 and 2015. The destruction is set to continue: The agency is considering removing another 7.4 million acres of piñon-juniper woodland across the Great Basin.

Over the years, I have often seen the evidence of this mass deforestation: in geometric clearcuts along the ranges of Catron County, New Mexico; in old-growth piñon forest reduced to pulp on the remote Tavaputs Plateau in Utah; in vast fields of stumps on rugged mountainsides in the basin and range country of Nevada. "Treated" is the term preferred by range managers to describe the undertaking. But this is little more than a bureaucratic euphemism: The trees are felled with saws, poisoned with herbicides, ripped from the ground with massive chains dragged by bulldozers, chewed to bits by machines called "bull hogs" and "giant masticators," and burned with hand torches and incendiary "ping pong balls" filled with potassium permanganate and dropped from helicopters.

Federal land managers once declared openly—even proudly—that this clearcutting was for a single purpose: to increase the land available for livestock grazing. "For as long as most of us have been aware of the piñon-juniper woodland type, we have looked upon the aggressive juniper and the scrubby piñon as weeds in need of eradication," wrote David Tidwell, a special assistant to the director of the BLM, in 1986. "That's not a goal to be ashamed of. Hundreds of thousands of acres of underproducing rangeland have been transformed into highly productive grazing land."

Today, the deforestation (or "conifer removal" in the clinical patois of the land managers) is couched in the buzzwords of ecological stewardship. The trees are being cut down to increase the "resilience" of woodland ecosystems or to reduce the "fuel load" in the nation's forests or, most often, to protect sagebrush-steppe habitat for the threatened sage grouse. "Removing encroaching juniper will improve conditions for greater sage grouse and many other species that depend on a healthy sagebrush-steppe ecosystem," reads a 2018 BLM press release calling for the elimination of more than half a million acres of juniper forest in the remote Owyhee Mountains, straddling Idaho, Oregon, and Nevada.

Juniper trees can live for centuries and, along with their cousins the piñons, represent the largest drought-adapted forest biome. | Photo by Robert Harding Picture Library

Many environmental activists and forest researchers dispute the ecological value of these projects. They argue that the assertion that slow-growing native forests are suddenly expanding out of control is oversimplified at best—and is, at worst, an ecologically devastating fantasy. University of Nevada ecologist Peter Weisberg said that any talk of expansion must be tempered by growing evidence of a climate-change-driven retreat. From 2005 to 2015, he and his colleagues surveyed 98 piñon-juniper sites across 11 mountain ranges in northern Nevada. In the canopies of drought-stricken forests, they found large numbers of bark beetles and other defoliating insects; in the understory, a profusion of invasive annual grasses. "We found an order of magnitude increase in mortality," he said.

Laura Cunningham, the California director at the Western Watersheds Project, says that the value of razing forestlands as a means to protect sage grouse is overstated and that razing imperils dozens of other species that depend on piñon and juniper forests for survival. "We've had decades of these piñon-juniper treatments, and yet every year the sage grouse populations go down," she told me. "The piñon-juniper treatments don't seem to be working."

Other environmental watchdog groups have fought the piñon-juniper clearings on the grounds that the supposed benefits aren't worth the ecological damage. "Fragile biological soil crust is the backbone of all life [on the Colorado Plateau]," said Kya Marienfeld, an attorney with the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance, which, along with the Western Watersheds Project, has successfully challenged the proposed chaining of 30,000 acres of piñon and juniper forests in a remote region of Utah's Grand Staircase–Escalante National Monument. "Dragging heavy anchor chains, driving bulldozers, and ripping out native vegetation as is done in these large-scale 'treatments' is absolutely devastating to this area."

Ron Lanner, a retired forestry professor and the author of The Piñon Pine: A Natural and Cultural History, has a broader complaint: He says that the government-sponsored deforestation campaign is founded on a kind of biological amnesia. According to Lanner, the tree clearing fails to consider historical evidence that piñon and juniper forests were widespread before white men arrived with their pickaxes and cattle. Using historical documents, Lanner has determined that close to 750,000 acres of piñon-juniper forest across Nevada were cut down between the late 1800s and early 1900s and that many of the trees were burned in massive, beehive-shaped kilns to create charcoal, which in turn was used as fuel to smelt silver. Thus, the advance often cited by range managers is, Lanner argues, merely the return of the forests to places where they once flourished.

"The BLM always talks about invasion," he said. "They never call it what it really is—regeneration."

LIKE A TERRESTRIAL TIDE IN A SEA OF GREEN, piñon and juniper forests have ebbed and flowed across the Great Basin and the Colorado Plateau for millennia as the climate has oscillated between wet and dry periods. Both trees are highly adaptable, inhabiting one of the largest elevation ranges of any conifer species; they can be found as low as 4,000 feet in the canyon country and sky islands of Arizona and as high as 9,000 feet in central Colorado. The two trees grow in mixed stands, with junipers dominating lower elevations and piñons proliferating higher up. The trees often take on different forms in their quest to survive. In exposed, windblown areas, they're squat and stout, almost shrublike. In sheltered sites where water is plentiful, the trees grow tall and slender, resembling Christmas tree firs.

After a 19th-century trip through the mosaic of sagebrush and piñon and juniper forests in Nevada, John Muir wrote:

Nearly every mountain in the State is planted with [piñon]. . . . Indeed, the entire State seems to be pretty evenly divided into mountain ranges covered with nut pines and plains covered with sage—now a swath of pines stretching from north to south, now a swath of sage; the one black, the other gray; one severely level, the other sweeping on complacently over ridge and valley and lofty crowning dome.

Old junipers have a strange tendency to go hollow in their midsections, so determining the age of the trees by counting their rings can be difficult, if not impossible. Other techniques, however, have revealed that piñons can survive for close to 1,000 years and western junipers more than 1,500 years. According to Lanner, piñons and junipers constitute the planet's largest drought-adapted forest biome. They also provide critical habitat for numerous bird species, including black-chinned hummingbirds, Clark's nutcrackers, ash-throated flycatchers, western bluebirds, juniper titmice, and Scott's orioles. The piñon jay is wholly dependent on the pine for food and nesting sites. In mature stands, the twinned tree species cast shade on the forest floor, providing a niche for native grasses, including Idaho fescue, Indian ricegrass, and bluebunch wheatgrass. These plants, in turn, provide forage for mule deer, elk, and antelope, which themselves are prey for mountain lions and, in the Greater Gila region of New Mexico and Arizona, scattered packs of Mexican gray wolves.

Some human cultures rely on the trees as well. For millennia, piñon and juniper have been critical sources of food and raw materials for the Indigenous peoples of the Great Basin and the Colorado Plateau, such as the Paiute and the Shoshone. Every September, the Walker River Paiute Tribe in Schurz, Nevada, celebrates its Pinenut Festival and Powwow. The gathering features arm wrestling and dancing as festivalgoers feast on breads and soups made from piñon nuts. Festivities culminate with the pine nut blessing, during which traditional songs and dances are performed in hopes of a bountiful crop of seeds the following year.

Paiute filmmaker and educator Myron Dewey says that he sees the effort to eradicate juniper and piñon as part of the centuries-old campaign to sever Indigenous people from their traditional food supplies and erase their culture. "When I go out to gather, it feels like I'm a trespasser on my own land," he said. Johnnie Bobb, chief of the national council of the Western Shoshone, told me that the cutting and burning of piñon trees often occurs without warning and without any consultation with the tribes. "The [BLM] is very sneaky about it," Bobb said. "One day you'll go out and the forest is just gone."

THE BLM'S LONG-RUNNING WAR on piñon and juniper began after World War II, as the United States looked for ways to feed a rapidly growing population. In order to ensure that beef remained cheap and a central part of the American diet, the livestock industry and public lands managers turned to the arid West. "The idea was that the public lands ought to shoulder their share of the burden of producing red meat," Lanner told me. The problem is that much of the land in the BLM's inventory was—and is—covered in piñon and juniper forests. "The trees were regarded as being an impediment to producing as much beef as they could."

Since the passage of the Taylor Grazing Act in 1934, ranchers in the West have been allowed to graze cattle on federal lands for a monthly fee of less than $1.50 per calf-cow pair. Today, according to the Public Lands Council, a pro-grazing group, the livestock industry holds leases on 250 million acres of public lands across the West. The bulk of these public lands grazing permits are administered by the BLM, which oversees an area comprising roughly one-tenth of the land area of the entire country. From its very inception, the BLM's pro-grazing mission has been tied to the removal of piñon and juniper forests.

Determining the exact scope and scale of deforestation is difficult, Lanner said. Projects are often staged over many years, and district offices are given wide latitude over when and where to conduct their tree-removal projects. "It's as if each ranger district is on its own program," Lanner said. The costs are also notoriously difficult to tally. According to a BLM resource manager in Ely, Nevada, the cost of removing trees is typically between $50 and $300 per acre, depending on the method of removal and the tree density. Fite told me that her research suggests that the costs are often far higher. She points to a project in central Oregon, where the BLM has estimated that clearing 26,000 acres of juniper will cost $13 million—a per-acre cost of $500. "It is very hard to get a full accounting," she wrote in an email.

In response to written questions, Derrick Henry, a BLM spokesperson in Washington, DC, stated that conifer encroachment is one of four "data layers" used for making land-management decisions in the Great Basin region (the others are "annual herbaceous, wildfire risk, and anthropogenic disturbance"). But the data the agency is using to guide the deforestation projects is severely limited. Michelle Jeffries, an ecologist and data specialist with the US Geological Survey, used a comprehensive Interior Department database called the Land Treatment Digital Library to tally all the acres of piñon-juniper treatment projects between 1957 and 2015. She found that there were records for only 230,000 acres of clearances—a tiny fraction of the total.

The dearth of data is emblematic of the BLM's lack of a cohesive plan for the management of these woodlands throughout the West. "Regarding a BLM P-J [piñon-juniper] strategy," BLM spokesperson Henry stated, "the BLM doesn't have one currently."

Critics, however, insist that at the district level, livestock interests continue to drive the BLM's actions. They also say that the BLM's cow-centric model of land stewardship is largely attributable to the fact that rangeland scientists, rather than foresters and ecologists, have come to dominate the ranks of the agency. "To a forester, a forest is a particular physical thing, a natural aggregation of trees, an ecosystem," Lanner said. "To a range scientist, however, 'range' is land that is used for forage by cattle. It says nothing about the land itself. If, for example, you release animals into a forest, that forest is now 'rangeland.' Put a cow in Central Park and it becomes rangeland."

TO SEE THE BLM'S LATEST and most ambitious deforestation project, I traveled an hour and a half southwest of Boise to where, last September, the BLM had burned a 13,000-acre parcel on Juniper Mountain, a rugged escarpment boasting old-growth forest. On a warm fall day, I met with Lance Okeson, the fuels manager for the Boise BLM district and the "burn boss" of the Trout Springs Prescribed Fire. We met in a parking lot beside the rodeo grounds in the small ranching community of Jordan Valley, Oregon, and climbed into Okeson's elephantine Ford F-250.

Soon we were bouncing up the washboard ruts of Mud Flat Road toward the scorched summit of Juniper Mountain. The road snaked back and forth between Idaho and Oregon, passing through ranchlands and pastures full of invasive cheatgrass and thistle. Okeson, who holds a degree in rangeland science from Oregon State University, explained that the Trout Springs burn was part of the much larger Bruneau-Owyhee Sage-Grouse Habitat Project, which calls for the removal, over the next 15 years, of 617,000 acres of juniper in southern Idaho, ostensibly to counteract decades of fire suppression. "We're hitting the reset button," Okeson said, by which he meant setting huge swaths of juniper forest ablaze and transforming them into sagebrush and grasslands—the preferred milieu of the sage grouse and the cattle rancher. The burn carried a price tag of $1.5 million, which he insisted was a bargain in terms of its ecological benefits.

As we pressed deeper into the public lands of the Owyhees, the invasive grasses began to thin. Idaho fescue, needle and thread, and penstemon sprouted between clumps of sagebrush and rabbitbrush, which bloomed in a riot of yellow flowers. Higher up on the hillsides, gnarled old junipers took the form of mature oaks, with stout trunks and wide canopies. Okeson kept telling me that such rocky uplands—sites conspicuously unsuited to grazing—are where junipers are supposed to live.

Okeson pulled over, and we stepped into a field scattered with sagebrush and medusahead. The usual bovine effluvia littered the dry soil. Okeson's eye was trained on the low ridge. In 2007, he said, the trees had been cut by hand. "You can see some old skeletons sticking up in there," he said, tracing a hand along the rise. Then he pointed to a smattering of small junipers growing among them. Areas like these, he said, are of particular concern and illustrate just how quickly, without intensive management, junipers can overtake an area. "I call it the 'Christmas tree farm effect.' You go through and cut it, and then about eight to 10 years later, you've got all these young trees that have responded from the first treatment."

Before ascending to the summit of Juniper Mountain (the irony of the name seemed lost on Okeson) to see the aftermath of the Trout Springs burn, Okeson showed me a valley that had been burned by the BLM two years earlier. Charred trees dotted the hillsides, but the valley floor was covered in a proliferation of native and introduced grasses. Before the burning, Okeson said, the valley had been badly overgrazed, reduced to a jumble of invasive weeds and scraggly junipers. "This is just pretty darn cool," Okeson said, running his hand through the thigh-high grasses.

We proceeded on, throttling up a steep, switchbacking grade toward the summit. We passed a set of rustic cabins and cattle pens—a backcountry cow camp—and eventually arrived at the outer margin of the Trout Springs prescribed burn. The grasses and sagebrush receded, and we entered an area of old junipers. This was the realm Okeson most feared, what he called the "phase three" forest. "Up here, we're on the verge of crossing a threshold," he said. Between the tall conifers, green shoots of native grasses and vivid hedges of ceanothus sprouted among bonsai-like mountain mahogany, a slow-growing species that provides important winter forage for deer and elk. But Okeson saw only the shadow of encroachment. "It's just a matter of years before we lose all of the sagebrush, so we need to reset the system."

Almost as soon as we entered the older forest, we began to see what that reset entailed. Scorched junipers, some easily over 50 feet tall, stood where they had died, and the forest floor had been transformed into a blackened hardpan. In places, the fire was still smoldering, and a small plume of smoke rose from a distant ridge.

We were now atop a high, rocky ridge, in the very zone where Okeson had stated, earlier in the day, junipers belonged—and where they would not be burned. I asked Okeson why the BLM had decided to intervene atop this remote plateau. This wasn't sage grouse habitat, after all. The slopes were far too steep and rugged, the forest too dense—too filled with raptors, surely—for the choosy birds to take up residence here. Other than the rough dirt road we were on, there was no infrastructure here to protect. Why not simply let nature take its course?

"People want assurances," Okeson replied. Evidently, he was referring to cattle ranchers, as they are among the few people who routinely use the area.

Rick Miller, a professor of rangeland science at Oregon State University, offered another reason for large burns like the one on Juniper Mountain. In the 1970s and '80s, burning was used on a very limited basis to clear trees, he said, and primarily to increase available grazing lands and to augment deer and elk habitat. Since then, the budget for conservation and maintenance on federal lands has plummeted, while appropriations for fire suppression and prevention more than tripled between 1995 and 2015. "With fire, it also comes down to acres and funding," Miller said. "If you want to sustain your program, you have to justify your existence." In other words, big burns may not always be ecologically prudent, but they are often economically expedient.

AFTER WANDERING CLEARCUTS and burn zones, I wanted to see a healthy, ungrazed tract of forest. Katie Fite said she knew just the place. We drove south from the Stinkingwater Range, past the shores of Malheur Lake, where in January 2016, a ragtag group of ranchers and militia members staged an armed takeover of US Fish and Wildlife buildings. The armed protest was a response to the conviction of two local ranchers who were found guilty of arson after they ignited wildfires to burn juniper trees on public lands where they grazed cattle.

At the foot of Steens Mountain, the evidence of BLM juniper deforestation was unmistakable, and in many places we saw dead junipers lying in massive slash piles. But Fite assured me that there remained places in the deep gorges nearby where old trees still stood.

The next morning, we hiked past an abandoned antique car riddled with bullet holes to the precipice of a steep gorge. In the recess, the blue vein of the Donner und Blitzen River flowed between dark volcanic walls. We picked our way along game trails, over boulders, through cliff bands. The forest quickly engulfed us, and the smell of soil and resin was rich and loamy. Birdsong resounded. "This is how a juniper forest is supposed to sound and smell!" Fite hollered.

Within 15 minutes, we arrived at the river's edge, its current cool and swift. In deep eddies along the grass-covered banks, Great Basin redband trout rose to the surface. A great blue heron landed just downriver from us and surveyed the canyon. We spotted deer and coyote scat. Sheltered under the canyon rim, this sliver of old-growth forest was alive and thriving—safe, for now, from hoof, chain, saw, and flame.

"Don't be fooled," Fite said as she took a sip from her water bottle. "If the BLM could figure out how to drag a chain down here, they would. Nothing out here in juniper country is ever safe. Nothing."

Take a Sierra Club trip to Oregon, Nevada, or Idaho. For details, see sc.org/adventure-travel.

This article appeared in the March/April 2020 edition with the headline "Slash and Burn."

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club