Deb Haaland, A Living Testament

The path to becoming the nation's first Native interior secretary

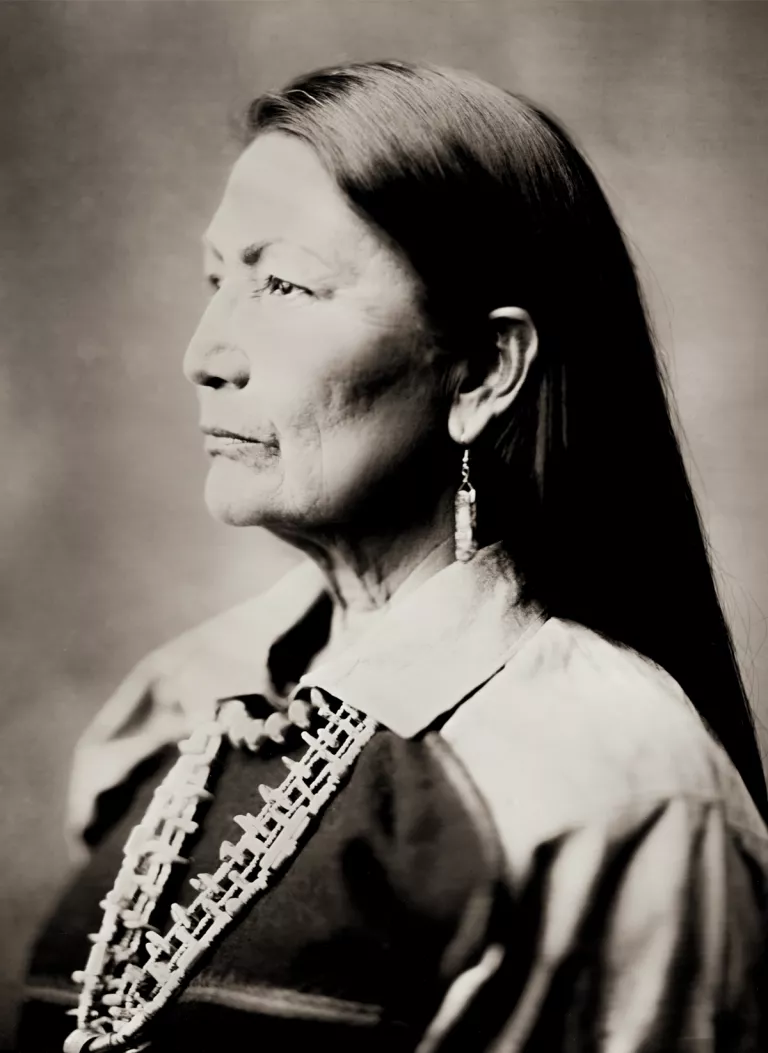

Photo by Shane Balkowitsc

SHAYAI LUCERO watched Deb Haaland's confirmation hearing from her flower shop on the Laguna Pueblo. She knows Haaland and her extended family. The floral business Lucero runs out of her converted garage used to belong to Haaland's sister.

These relationships are as typical as any across the reservation—a sprawling community about 50 miles west of Albuquerque, New Mexico, comprising six small villages, a colonial mission, and the now-parched lagoon that inspired the pueblo's Spanish name.

In the flower shop, a laptop played C-SPAN's livestream of the proceedings.

Haaland arrived at the Dirksen Senate Office Building with her arms fully loaded. On one side, she held a big white binder at her hip. On the other, she cradled an ornately painted Pueblo pottery bowl like a baby. The New Mexico representative wore a charcoal-gray pantsuit, a basic black top, and strands of chunky turquoise stones around her neck. Tacked to her lapel was a congressional pin. It was February 23, 2021—mere weeks into her second term.

Haaland gifted the pottery to Don Young, a House Republican from Alaska. He had agreed to give a rare endorsement at the start of Haaland's Senate hearing despite their disagreements over drilling for fossil fuels. Affectionately calling his colleague "Debbie," the senior statesman explained to the gathering of mostly white and male lawmakers how he and Haaland had become fast friends. "It's my job to try to convince her that she is not all right, and her job is to convince me I'm not right," he said. "She will listen to you."

John Barrasso, the ranking member of the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee, noted Haaland's epoch-making hour. "If confirmed, she would be the first Native cabinet secretary," he said. "For that reason, her nomination is historic and deserves to be recognized."

He nodded gentlemanly toward the cabinet nominee, flipping a page from his script. "At the same time," he said, sighing, "I am troubled by many of Representative Haaland's views—views that many in my home state of Wyoming would consider as radical."

At 60, Haaland has a face that reflects a lineage of Pueblo matriarchs. In 2018, she became one of the first two Native American women ever elected to Congress, along with Ho-Chunk Democratic representative Sharice Davids from Kansas. Her nomination for secretary of the interior largely came about because Indigenous activists had a wild idea, tested it, and lobbied President Joe Biden to follow along.

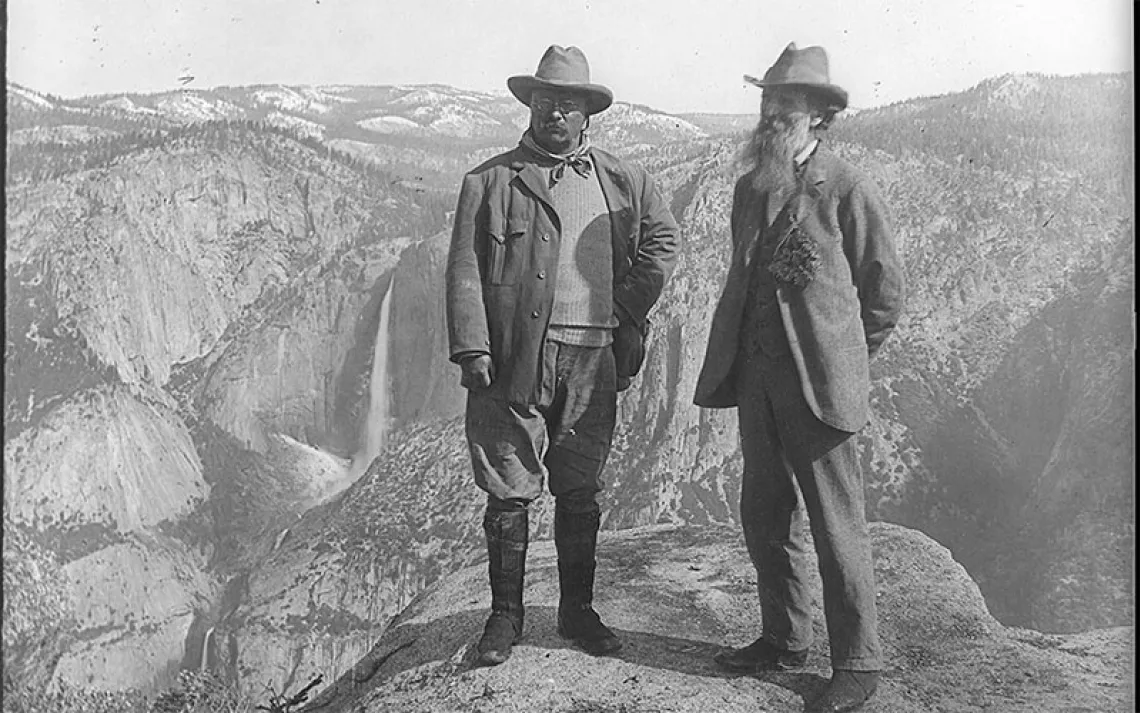

Deb Haaland is sworn in as the nation's first Native interior secretary. | Photo by Lawrence Jackson/White House

Haaland greeted lawmakers in Keres, the language of the Káwáigamé, or People From the Small Lake, Laguna. "Guwadzi hauba," she said, introducing herself by clan: Turquoise. Then she spoke of summers spent in Mesita village. "It was in the cornfields with my grandfather where I learned the importance of water and protecting our resources—where I gained a deep respect for the earth." She encouraged Republicans, Democrats, and independents in the committee to consider their shared love for the outdoors.

But Republican senators wanted none of that. Barrasso worked to set the tone: a grilling.

"I'm an orthopedic surgeon," he told Haaland. "And just a couple of months ago, you tweeted, 'Republicans don't believe in science,' a pretty broad statement."

"Senator, I . . ." Haaland gently waved her hand, searching for a response. "Yes, if you're a doctor, I would assume you believe in science," she said.

Science. The word came up frequently during the proceedings, revealing the cultural divide over whether to trust expert analyses on current issues like the coronavirus and climate change. For two days, oil-backed Republicans took turns expressing their frustrations. Senator James Risch of Idaho stirred tensions when he repeatedly pressed Haaland about the Keystone XL Pipeline—never mind that the energy project is determined by presidential permit and not by the Interior Department. Senator Steve Daines, the most vocal of Haaland's critics, raised concerns about energy-sector job losses for his Montana constituents. Barrasso, meanwhile, insinuated that the congresswoman was a drug peddler for proposing cannabis cultivation to offset oil and gas revenues. At every turn, Haaland responded with inscrutable poise.

On March 15, the Senate gathered to vote on whether she would become the first Native person to lead the Interior Department. It was a historic day.

Lucero was again at work, placing bright marigolds into a perfect ring, a wreath that would lie on the grave of a young tribal member. It had been one year since Laguna Pueblo had closed its reservation borders in response to the pandemic; the coronavirus had hit the community particularly hard. The grieving she'd seen as the only florist on the reservation weighed on her.

Lucero is a wife and a mother, a daughter and an entrepreneur. She's also a former Miss Indian World, a title she preserved in a collage of decorative pins, ticket stubs from memorable events, and photographs of her travels, hanging near her dining room. The year she reigned, in 1997, she journeyed to Japan, performed at Lincoln Center, and made stops across Indian Country, including an Iñupiat blanket toss in Alaska. Unlike other pageants, Miss Indian World is less about outward beauty and more about deep cultural ties. For the traditional talent competition, Lucero delivered a presentation about Pueblo plant medicines.

As the Senate vote got underway, Lucero's mother, Cecelia, gave an enthusiastic play-by-play. "Murkowski for Haaland," she said while her daughter focused on her sympathy wreath.

When the voting stopped, Lucero put down the marigolds and joined her mother at the laptop. The final vote was 51 to 40—confirmed—with most Republicans voting against Haaland. Lucero marked the moment by snapping a screenshot. She looked at her mother, expecting to see her beaming. Instead, she saw tears.

Laguna Pueblo, where Haaland grew up. | Photo by Christian Heeb/laif/Redux

"I just keep thinking about all those Indian leaders who trekked from their homes to try to get the government to listen to them," Cecelia told her daughter. "Centuries of chiefs and tribal leaders."

Lucero's mother might have been referencing any number of Native delegations who for over two centuries and during almost every presidential administration had visited the White House, and specifically the Interior Department, to advocate for themselves—their sovereignty, their land, their right to pray. So often these trips were futile. A rare exception came in 1922, when the All Indian Pueblo Council stopped a bill that would have seized some 60,000 acres of Pueblo land and disrupted their ceremonies.

"People in Indian Country, it just seems, we have this sense of relief," Lucero said. "We've been ignored for so long."

ALMOST EVERYONE CALLS Debra Anne Haaland "Deb." Native millennials go further—to them she is "Auntie Deb." Becoming "Madam Secretary" has catapulted her to the status of an Indigenous icon. She's a meme. She's a GIF. She's some artist's latest beadwork. Across social media, one of her most famous lines is now hashtagged on a regular basis: "Be fierce."

Her appointment as the first Native American to lead the Interior Department is more than riveting considering the department's legacy and documented abuse of Indigenous people. In 1851, two years after the department was created, President Millard Fillmore appointed Oliver M. Wozencraft as an Indian commissioner to form treaties with California tribes. Gold diggers had been scouring the Sierra Nevada foothills as militias carried out state-sponsored Indigenous genocide. There was a maniacal mood in what California's first governor called a "war of extermination." Wozencraft deceived tribes into signing 18 treaties—land negotiations that he knew Congress would never ratify. Interior Secretary Alexander H.H. Stuart helped break these pacts, writing a series of letters to Fillmore justifying the abrogation.

One hundred and seventy years later, Haaland quoted Stuart in a speech upon accepting her nomination. "This moment is profound when we consider that a former secretary of the interior once proclaimed his goal was to, quote, civilize or exterminate us," she said. "I am a living testament to the failure of that horrific ideology."

Haaland was sworn in on March 18 wearing a rainbow-striped ribbon skirt and tall calfskin moccasins, her initiation in joining the most diverse cabinet in US history. Only six of the president's 15 secretary picks are straight white men—the lowest number in any administration.

Indigenous people have inhabited the North American continent for millennia, since well before European explorers arrived in the late 1400s. Despite what followed—calculated land dispossession by way of massacre, removal, and ethnic cleansing—some 3 million people are citizens of today's 574 federally recognized Native nations. With barely 1 percent of the US population, Indian Country is one of the most overlooked and misunderstood communities in America. According to a 2015 report in Theory and Research in Social Education, 87 percent of state history standards do not mention Indigenous people after the year 1900. That could explain why many Americans' knowledge of Indigenous history is so limited or, in the case of former senator Rick Santorum, rife with ignorance. "We birthed a nation from nothing," Santorum said in an April 23 speech before the conservative Young America's Foundation. "I mean, yes, we have Native Americans, but there isn't much Native American culture in American culture."

Haaland hikes in Bears Ears National Monument with tribal leaders and Utah politicians. | Photo by Rick Bowmer/AP

For many, Haaland is the most visible reminder that Native people are still here. As the leader of the $12.6 billion Interior Department, she is a beacon of progressive policymaking, responsible for overseeing nearly a fifth of the nation's public lands across 11 agencies, including the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Secretary Haaland is now poised to prioritize, for the first time in this country's history, Indigenous affairs. Even before she came to Congress in 2019, the Pueblo politician had spoken out against fossil fuels. In 2016, she drove from Albuquerque to Standing Rock, North Dakota, to stand with water protectors protesting the Dakota Access Pipeline. At the beginning of her first term, Haaland joined other progressives—Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Ayanna Pressley, and Ilhan Omar—at a press conference introducing the Green New Deal.

By the end of Haaland's first term, five of her signature bills had become law, all but one of them related to Indian Country. The Not Invisible Act is now being implemented in the Interior Department. This law and its companion legislation, Savanna's Act, were signed by President Donald Trump last year. Together they call for enhanced policing to curb the dramatic rate at which Indigenous people are disappeared or found dead. A decades-long grassroots effort to address the "missing and murdered" was galvanized in 2017 after the horrific murder of Spirit Lake mother Savanna Lafontaine-Greywind. Investigators in Fargo, North Dakota, bungled the job, revealing the subtleties of police bias. In her second week at the Interior Department, Haaland established a Missing and Murdered Unit to help carry out these two laws.

"We're looking at systems as a whole to be fundamentally delegitimized, so it's a powerful moment," said Sam Torres, director and researcher for the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition. "In a way, we're starting to scratch the surface on correcting injustices that have been hundreds of years in the making."

Torres has been examining cycles of violence in Indian Country triggered by the 1819 Indian Civilization Act, a federal policy designed for the cultural genocide of Indigenous people through a network of Indian boarding schools. The most notorious of these forced-assimilation programs was the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania. Its stated mission: "Kill the Indian, and save the man."

In her 2018 campaign blog, Haaland wrote that her Laguna Pueblo great-grandfather had been sent by train to attend Carlisle in 1881. In a 1995 essay for New Mexico Magazine, she said that her grandparents had been similarly separated from their families when they met as children at a boarding school in Santa Fe.

In June, before hundreds of tribal leaders attending the online National Congress of American Indians mid-year conference, she announced the first-ever investigation into the US boarding school policy, the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative. Haaland confided to them that her role as Madam Secretary was one of the most important challenges of her professional life.

"I come from ancestors who endured the horrors of Indian boarding school assimilation policies carried out by the same department that I now lead, the same agency that tried to eradicate our culture, our language, our spiritual practices, and our people," Haaland said. "We must shed light on the unspoken traumas of the past, no matter how hard it will be."

BEFORE THE RAILROAD arrived in the 1880s, men in the village of Old Laguna would travel five or so miles to a jutting mesa where cornfields and fruit trees flourished in the summer. The farmers lived in makeshift camps until it made sense to permanently settle there. Today, Mesita village is a patchwork of roughly 40 homes, a Catholic church, a plaza, and a meeting hall. The occasional train passes along a northern sandstone bluff. To the south, a steady stream of 18-wheelers, RVs, and cars roll by on Interstate 40.

Helen Steele, Haaland's grandmother, was raised in Mesita. At age 18, she married Tony Toya, a young man from the nearby Jemez Pueblo. He was courting her the day railway recruiters offered him a job some 200 miles west in Winslow, Arizona. The young couple moved there and settled behind a roundhouse, where a colony of Laguna workers had formed. They lived in homes converted from castaway boxcars. They spoke Keres and baked bread in handcrafted hornos, or mud ovens, just as they did back home. The Toyas, who were determined to maintain a connection to Mesita, took advantage of free train rides and returned to the reservation often, especially to tend to summer crops. Haaland was born in Winslow, and these experiences of her grandparents became a defining part of her upbringing.

In 1974, Haaland was a freshman at Albuquerque's Highland High. Before then, she had bounced among more than a dozen schools, the sheltered daughter of two military parents. John David "Dutch" Haaland, a marine officer, had saved six lives during his two-year tour in Vietnam, for which he was awarded the Silver Star. Mary Toya, Haaland's mother, served in the US Navy and kept a home with floors so clean you'd slip on them. As the war played out on TV, Haaland said, some days the news reports would bring her father to tears.

After graduating high school in 1978, Haaland packed her bags and moved with a friend to Los Angeles. Her ambitions were straightforward: "Just to meet some movie stars," Haaland told me. Beyond that, they didn't have much of a plan. Going broke brought her back to the popular Albuquerque bakery where she'd been working since age 14.

For Haaland, understanding her Indigeneity began in adulthood when she entered the University of New Mexico (UNM). She was 28, and her guides were Native authors and poets exploding onto the national scene. Today's US poet laureate, Joy Harjo, who is Muscogee, was on her roster of instructors. Haaland read books with plotlines about characters returning to the reservation with "feet in two worlds." Back then, Indigenous studies programs hardly fit the rubric for higher education, but Native literature and poetry laid that foundation. And it spoke to Haaland, who had been dancing on ceremonial feast days and Christmases since she was a young girl. "Sometimes I'd be the only one out of my family dancing," she said. "Nobody else would dance."

On graduation day in spring 1994, a very pregnant Haaland wore UNM's red cap and gown. Four days later, at 33, she gave birth to a child she named Somàh. Single motherhood would alter the trajectory of their lives. "It was a choice I made to be a single mom," Haaland said in a campaign video in 2018.

When Somàh turned two, Haaland started her own company, Pueblo Salsa, as a way to spend more time with her child. She worked out of a commercial kitchen and sourced some of the most sought-after red chilies in northern New Mexico. She sold jars that were stocked at local grocery stores and other small businesses statewide. But she struggled. When not making salsa, she was delivering it to her customers. In between, she traded preschool duties for Somàh's free tuition while filing the occasional magazine essay as a freelance writer.

By 2002, Haaland had become drawn to political organizing. That year, South Dakota senator Tim Johnson eked out a narrow reelection victory, by 528 ballots, largely credited to Lakota voters. "When I saw what the Indian vote had done in South Dakota, I said, I bet we can do that here," Haaland recalled.

She applied to law school, sold her company, and returned to UNM in 2003. But these ambitions threw her finances into tumult. Living away from New Mexico for a short stint had made her ineligible for in-state tuition. Haaland describes those years as lean—a diet of pinto beans and tortillas. Yet, when she sought emergency food stamps for the first time, she was denied. She had "too many assets," she was told. She walked away feeling too poor to feed her tiny family but not poor enough in the eyes of the government. It took a brush with homelessness—essentially, couch surfing among friends—for her to become eligible.

Years later, Haaland's efforts began to pay off: She was hired by President Barack Obama's campaign to secure the Native vote. She became the state Democratic Party's Native American caucus chair. She ran for lieutenant governor of New Mexico in 2014, lost, then circled back to the state Democratic Party as its first Native chairperson.

When Haaland was scoping out locations to kick off her For Congress, For Us campaign in 2017, a former professor at UNM Law School, John Feldman, offered up his juke joint. Two years later, he hosted the launch of her reelection campaign. "She's a team builder," Feldman said. "And not just everybody has that. That's what I've seen all along."

SHAYAI LUCERO REMEMBERS the day in 2004 when Haaland the canvasser came knocking on her door. Haaland had studied the data and noticed that Lucero rarely missed an election. Haaland asked her if she would mind driving Lagunas to the polls. "That was her grassroots effort, to get people to realize the importance of our vote," Lucero said. "And the history of Miguel Trujillo."

After World War II, Native veterans like Trujillo returned as heroes, but to a country that disenfranchised them. Across New Mexico, Native Americans did not secure the right to vote until 1948, through a lawsuit that Trujillo filed and won. But it took time for Natives in New Mexico to trust the electoral process, even in the 2000s, when Haaland canvassed area pueblos. Trujillo's legacy was mostly suppressed in obscure history books until Haaland kept mentioning his name. She'd reserve Pueblo recreation halls, bring pots of green chile and a stack of tortillas, and register Native voters.

The night Haaland became one of the first two Native women elected to Congress, she acknowledged—who else?—Miguel Trujillo. "Seventy years ago, Native Americans right here in New Mexico couldn't vote," she said to her supporters. "Today we all came together, and we said we still believe in the American dream, and American democracy, and in hope."

The room roared.

Across the 19 Pueblo governments in New Mexico, top leadership roles are mostly reserved for men. For Lucero, that fact has deep personal roots. "As a young woman, I always told my dad, 'Oh, I would love to be governor,'" she said. "And he would always have to burst my bubble: 'You're never going to be governor.'"

Many Pueblo women see Haaland's interior secretary appointment as a turning point.

"We need to be giving her our support," Lucero's mom said. "She's going to be protector of our Mother. We need to support the woman who's going to protect Her."

HAALAND'S ENTOURAGE ZIGZAGGED up the Moki Dugway on a morning so clear and golden you could see why tourists love Bears Ears. The tawny earth and sandstone bluffs were only the beginning of a seemingly unbroken landscape.

Less than a month after being confirmed as interior secretary, Haaland was ascending a snakelike road up to Muley Point that was chiseled into Cedar Mesa for the Happy Jack uranium mine 70 years ago. She passed a few guardrails that don't hide the fact that the occasional vehicle has gone over the edge. Eventually the silhouettes of two buttes, Bears Ears, came into sight.

It was quiet on the mesa during a prayer. As the top administrator of the nation's public lands, Secretary Haaland had come to Utah to update President Biden on an American controversy: the making and breaking of a monument. For more than a century, the state's southeast corner has been a resplendent backdrop for the racism that provoked the dispute over protections for the area. The mostly white, mostly Republican majority in Utah favors the loosest federal restrictions over the region, while many others—Natives, scientists, and environmentalists—say it is deserving of so much more.

Looting by locals has been a key catalyst for such contention. The decades-long pilfering of Indigenous holy objects got so bad that it led to unprecedented crackdowns by the Bureau of Land Management. One sophisticated sting in 2009 exposed looters' houses stuffed with artifacts, including an unearthed cradleboard with an umbilical cord.

"They call it pot hunting, but it was grave robbery, really," former interior secretary Sally Jewell told The Washington Post in 2019. Jewell was the head of the Interior Department when President Obama created the 1.35-million-acre Bears Ears National Monument in 2016. For conservatives across Utah, the designation felt like federal "overreach." And they let President Trump know it after he succeeded Obama in the White House.

In the three years since Trump shrank Bears Ears, the threats to this treasured ecosystem have mounted, according to stakeholders who demand that the monument be restored. The hazards, aside from prolonged plunder, range from vandalism and over-visitation to unmonitored off-roading. More politically charged issues are linked to uranium mining and oil and gas drilling—all on a site considered a sanctuary to Native Americans.

"It is much like the Mormon temple up in Salt Lake City," Clark Tenakhongva said at a press conference during Haaland's visit. The vice-chairman of the Hopi Tribe is also co-chair of the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition. "If you desecrate, destroy our shrines, our temples down here, basically you're destroying our culture, our religion, our lifeline."

The land here is sacred to many of the region's Native Americans, including a Pueblo diaspora who lived among these sunburned mesas about 1,200 years ago, before a megadrought forced their migration to the banks of the Rio Grande. It's because of this that Haaland describes herself as a "35th generation New Mexican." And it's why her first act as a representative was drafting legislation to restore the protections to Bears Ears undone by Trump. That bill failed, making it unfinished business in her first official tour as interior secretary.

In the afternoon, Haaland hiked Butler Wash with Tenakhongva and other tribal leaders, along with Utah Republicans and the state's governor, Spencer Cox. Conspicuously missing was senior senator Mike Lee, who had pestered Haaland about Bears Ears on both days of her confirmation hearing. Lee had invited Haaland to Utah, but now that she was there, he wasn't.

If such treatment bothered Haaland, she appeared to have brushed it off. At one point, she stood in the center of a selfie snapped by Governor Cox; his long right arm stretched far enough to frame the shot with Senator Mitt Romney, who leaned in, off to the side. They smiled behind their masks. Romney and other Republicans want Haaland to tell Biden to back off, to let Congress decide the future of the monument.

"I think this is an opportunity to find common ground," Romney said. "No pun intended." And he promoted a "working together" approach, though the lawmaker, along with Lee, had been among the 40 senators who had voted against Haaland's confirmation.

In a report sent to the White House in early June, the interior secretary advised Biden to reinstate the original boundaries at Bears Ears as well as Grand Staircase–Escalante National Monument. Utah is now poised to sue.

"Sister," Tenakhongva said to Haaland from the podium during the press conference. He then addressed his opponents' gripes about government "overreach": "Wait until you become a brown-skinned person and a Native American," he said, his tone filled with frustration. "That's when you will talk about overreach of the American government."

Tenakhongva was crestfallen when Trump reduced Bears Ears. In December 2017, on his first day in office as the Hopi vice-chairman, he sued the president. The lawsuit is on hold pending Biden's review. Tenakhongva explained to Haaland what it meant to have Obama designate a monument that, for the first time ever, honors traditional knowledge rooted in the land—the plants, the water, and the spirits of their kin. "It took years of hard work for us to get to that point," he said. "It's never been fair."

While lobbying by at least one uranium company bolstered Trump's decision to shrink the monument, the sense industry-wide is that mining the mineral is too expensive. Meanwhile, the Utah Geological Survey reported in March that all 255 oil and gas wells situated within Bears Ears have been abandoned since 1992.

Still, a recent uranium reserve included in the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan raises speculation. Last year the same uranium company that lobbied Trump, Energy Fuels, coordinated campaign contributions for members of Congress who supported the creation of a $75 million federal uranium stockpile for its conventional mill near Bears Ears, the only one operating in the United States. In its press release, Energy Fuels applauded the reserve. And it thanked a single senator by name: John Barrasso.

On her hike to Butler Wash, Haaland found herself at the edge of a rare perennial spring, a lifeline to the arid mesa. It glinted at her. Tenakhongva and other Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition members burned earth medicines and offered them to the water. For the second time that day, in the home of her ancestors, Haaland acknowledged the land with gratitude and prayed. "The earth holds so much power," she said as the desert light started to wane.

Hands shoved in pockets, a medicine bundle dangling around her neck, Madam Secretary stood in the Valley of the Gods as sundown gave shadow to the land.

This article appeared in the Fall quarterly edition with the headline "A Living Testament."

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club