Planned Obsolescence: What Is It and How to Overcome It

Planned obsolescence is why we see software mysteriously slow down, furniture designed with hollow legs and cheap staples, and clothing burned because it can't sell fast enough.

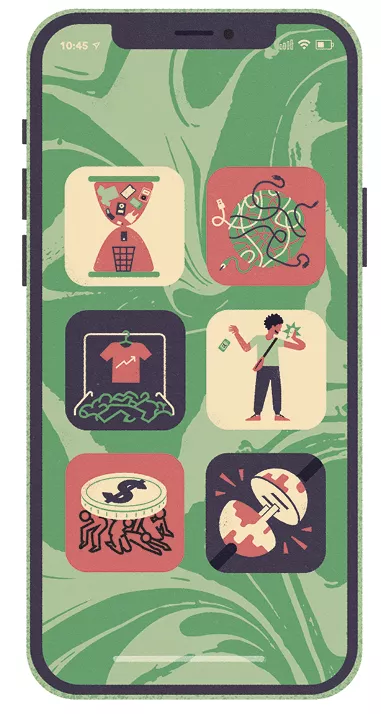

Illustrations by Mike Ellis

In 2020, people worldwide bought some 24 billion pairs of shoes, 64 million cars, and 1.4 billion smartphones—200 million of them from Apple. More than 80 percent of iPhones sold last year went to "upgraders," not first-time buyers. It's all part of business as usual.

Since the 1920s, when lightbulb manufacturers teamed up to purposefully limit the life spans of their products, companies have been locked into a business model rooted in the concept of planned obsolescence. To "grow," at least the way economists define it, corporations have to sell us more stuff every year—which is why there are ever-cheaper products made from low-quality or even toxic materials by people working in unjust conditions.

Planned obsolescence is why we see software mysteriously slow down, furniture designed with hollow legs and cheap staples, and clothing burned because it can't sell fast enough. As repair shops close, landfills expand. How did we get here? How can we change course?

The Components of Planned Obsolescence

Design

Planned obsolescence is determined largely by the materials a manufacturer chooses to use and how they're put together (think phones with screens glued in place). If a company's main source of revenue is selling more stuff every year, there's little incentive to design for durability, longevity, and repair.

Linear Growth Models

Our reigning economic model's limited definition of growth means that businesses don't invest in alternative revenue streams, like repair, service, and resale. "Negative externalities" like pollution aren't factored into the bottom line, and shareholder profit trumps all.

Low wages

The economic model that demands nonstop growth rests on a foundation of wage inequality and human rights abuses. Without international labor standards, it is easier to make new, cheap items than to service old ones.

Product Logistics

In addition to basic design, a host of secondary characteristics and logistical quagmires make it hard to keep an object in use—for example, accessories that aren't interchangeable, parts or manuals that aren't readily available, and warranties and service policies that prioritize replacement over repair.

Marketing

Advertising reinforces the notion that we should run out and get shiny new models. Cultural messages teach us to devalue our attachment to the things we already have.

Disconnection

As globalization increasingly separates end users from the making of products, our sense of value becomes distorted, creating both physical and psychological distance between the manufacture and the use of our stuff.

A History of Planned Obsolescence

1924

An international group of lightbulb manufacturers called the Phoebus Cartel agrees to limit the life span of bulbs to around 1,000 hours—significantly shorter than the previous standard.

1927

General Motors head Alfred P. Sloan introduces "dynamic obsolescence" to maintain sales as the automobile market begins to reach a saturation point. GM unveils the industry's first design studio to foster demand for updated car styles and colors.

1929

Christine Frederick publishes Selling Mrs. Consumer, which champions "progressive obsolescence," a plan to stoke consumption by tapping people's love of changing fashions: "The same thrill that women have always had over new clothes, women are now also obtaining over replacement, changes, reconstruction, new colors and forms in all types of merchandise."

1932

Bernard London publishes a series of essays that call for ending the Depression through "planned obsolescence," a scheme similar to Frederick's but centrally managed. After a predetermined amount of time, manufactured objects would be "legally 'dead'" and recalled. People would then buy new goods, "and the wheels of industry would be kept going."

1954

Brooks Stevens popularizes the notion of planned obsolescence through advertising, "instilling in the buyer the desire to own something a little newer, a little better, a little sooner than is necessary."

1989

The New York Times coins the term "fast fashion" upon the opening of a flagship Zara store in New York.

1996

IKEA launches the Chuck Out Your Chintz campaign, encouraging British women to dispose of their stodgy old furniture and embrace the "freedom" of regularly replacing living room sets.

2001

Apple's newly introduced iPod has an unreplaceable battery that lasts only about 18 months, sparking outrage.

The (Circular) Path Away From Obsolescence

Individuals

Send signals to the marketplace, demonstrate demand for durability, and live in a way that aligns with your values.

- Have good stuff.

- Buying new stuff should be rare. Seek out new goods that are durable, repairable, sustainably sourced, and ethically produced.

- Don't have too much.

- Stuff is just like food—too much of a good thing causes problems. Reduce empty "stuff calories" by buying less and choosing carefully.

- Look for mostly reclaimed stuff.

- Rebalance your stuff diet by making used goods your first choice whenever possible.

- Care for it.

- Make repair and maintenance part of your routine and your budget by spending time and money on taking care of what you already have.

- Pass it on.

- When an item has reached the end of its useful life, or its use in your life, pass it on to someone who can use it.

Manufacturers

Companies can meet the growing demand for sustainability by building goods and services that make it possible for people to change their habits. Circular business models are nothing new but are taking off in new ways. In apparel, resale has grown more than 21 times faster than traditional retail in recent years.

- Develop multiple revenue streams—not only from selling new stuff but also from resale, repair, upgrade, rental, and service models.

- Move away from the "race to the bottom" on pricing. Sell fewer items, but make money from the same item multiple times by offering resale and repair.

- Create stronger relationships with customers based on quality, transparency, and service.

Policymakers

Help create the incentives (positive and negative) that will accelerate and scale positive changes. The following are a few models, from local to global:

- "Pay as you throw" waste services have been shown to reduce waste sent to landfill and help incentivize individuals to "pass it on."

- Extended-producer-responsibility laws make sure manufacturers and retailers consider the full life cycle of a product.

- Right-to-repair legislation is on the agenda in at least 25 states; it would help protect farmers, small-business owners, and individuals who want to be able to fix their own tools and equipment.

- International fair-labor standards are the holy grail of healthier patterns of consumption; our present system is built on low wages in manufacturing countries around the world. A truly circular, ethical model hinges on people being paid fairly for their work.

This article appeared in the Fall quarterly edition with the headline "Built Not to Last."

Overcoming Planned Obsolescence

2012

Massachusetts passes the landmark Motor Vehicle Owners' Right to Repair Act, targeting the automotive industry. In 2020, an amendment is added to close loopholes in the original law.

2013

Dutch company Fairphone releases a smartphone that is sustainable and ethically produced, modular, repairable, and upgradable.

2017

Patagonia introduces Worn Wear, offering used clothes for sale online.

2017

Sweden introduces a tax break for repairs of big-ticket items such as refrigerators. Consumers get half the labor cost back in their income tax rebate.

2020

IKEA commits to going 100 percent circular by 2030. Soon after, Target commits to becoming a circular business by 2040.

2021

France's repairability index—which scores products according to ease of fixability—comes into effect; the aim is to achieve a 60 percent repair rate for electronics within five years. Policymakers plan to incorporate a durability index by 2024 to measure product longevity.

2021

The New York Senate passes right-to-repair legislation with overwhelming bipartisan support.

2021

President Joe Biden issues a right-to-repair executive order, calling on the Federal Trade Commission to enforce rules for manufacturers that will enable consumers to repair their own goods.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club