Can Long Beach Achieve Climate Resiliency As Sea Levels Rise?

With the clock ticking, city leaders and climate experts work to educate the public

Photo by MattGush/iStock

For Henry Nagano, summers in the coastal city of Long Beach, California, have long meant swimming laps up and down Alamitos Bay. Originally from Japan, Nagano came to the United States on a scholarship to attend MIT. After graduating with a degree in space systems and engineering, he decided to live and work permanently in the US. He settled in Long Beach, in the island community of Naples—a Venetian-style neighborhood of three low-lying contiguous islands, where Tudor- and Victorian-style homes mingle with surfer bungalows joined by a lattice of bridges and boat slips for gondolas and canoes.

“Living in Long Beach is like living in heaven,” Nagano, who has lived there for nearly 50 years, told Sierra. “I’ve traveled all over the world doing consulting for the US government. No place will ever beat Long Beach for me. But there used to be a lot more beach area than there is today. It will be very sad if we lose this scenery because the city and the state would not prevent the submersion of these beautiful islands.”

As it does for many cities along the Pacific coast, climate change poses a serious, some say existential, threat to residents of Long Beach, both from the impacts of sea level rise on low-lying neighborhoods like Naples and from extreme heat. Long Beach—a port city of nearly 500,000, where the serpentine Los Angeles River bottoms out into the sea—is not as large as its sprawling neighbor, L.A., just a 25-mile drive up the 710 freeway, but large enough to represent a test case for how coastal cities throughout California and around the country manage and mitigate the impacts of climate change.

Low-lying neighborhoods throughout the Long Beach Peninsula, Naples, and Belmont Shore—where the median price of a home costs nearly $900,000—will become increasingly inundated by chronic flooding as sea levels rise. Warming temperatures will make air pollution worse as heat triggers photochemical reactions along its smoggy lower atmosphere in a city that already ranks as the number one most polluted city (along with Los Angeles) in the United States, due in part to the trucks that come into and out of the ports. An estimated 15 percent of residents suffer from asthma. Long Beach has seen record-high temperatures in the past decade; in February, a heat wave led to record-breaking temperatures at Long Beach and Los Angeles International Airports.

The impact on coastal habitats could be just as severe. Much of the habitat not just in Long Beach but up and down the California coast could be lost if temperatures continue to warm and seas continue to rise, according to a 2018 study from the Nature Conservancy and the California State Coastal Conservancy, Conserving California’s Coastal Habitat: A Legacy and a Future With Sea Level Rise. Up to 55 percent of California’s coastal habitats could be lost, according to the study, including beaches, marshes, and tide pools.

“That could have cascading impacts,” Alyssa Mann, coastal project director at the Nature Conservancy, told Sierra. “There are a number of species that are only found on the coast. When you have 55 percent of loss, that cascades down to about 39 rare, threatened, and endangered species that are highly vulnerable.”

The study also projected that 41,000 acres of already conserved land throughout the state could be drowned by subtidal waters.

Local climate experts hope that Long Beach can serve as a model for how city leaders, scientists, engineers, and residents think about and try to solve the challenge of coastal living in a time of climate change, whether it’s an increase in heat waves, drought, or sea level rise. When sea level goes up a foot, what are the options? When it goes up two or three or four feet, how do the options change over time? At what point does a community run out of options and have to consider the ultimate form of climate adaption: strategic relocation, also known as managed retreat? Such measures will require considerable financing, most likely from some kind of joint public and private partnership. Who should pay?

These are just some of the questions that Dr. Jerry Schubel, president and CEO of the Aquarium of the Pacific, puzzled over during a recent public workshop the aquarium hosted on sea level rise in partnership with the Nature Conservancy. While turnout for the March 9 workshop was light due to the coronavirus crisis, a dynamic discussion got underway between attendees and workshop presenters, which, in addition to Schubel, included Dr. Reinhard Flick, a coastal oceanographer, and Walter Crampton, a professional coastal engineer.

“This is not fake news,” Flick stated as he methodically reviewed the realities of global warming and sea level rise during his presentation. “This is long-established science.” He showed a picture of John Tyndall, a 19th-century chemist who in the mid-1800s was one of the first to describe the physics of the greenhouse effect. “Sea level rise is sharpening and making more acute the challenges and the trade-offs that we have faced in the California coast and most other coasts all along, ever since development started in California 150 years ago.”

The workshop was just one in a series that the aquarium and the Nature Conservancy have held to try to engage the public in a discussion of both the realities of climate change and the solutions; in this case, presenters focused more on short-term engineering options. One could involve the L.A.–Long Beach outer breakwater, which the Army Corps of Engineers constructed in collaboration with the city in the 1940s in an effort to protect US Navy ships docked there. The breakwater shelters most of Long Beach from the waves of the Pacific Ocean. Extending the breakwater could protect the city from offshore storms and storm surges, according to Crampton, who also advocated for stabilizing beaches through sand and dune replenishment.

For the past five years, Schubel has been collaborating with city managers and Mayor Robert Garcia, who, in his January 2015 State of the City address, announced a push to make Long Beach a climate-resilient city. Garcia followed up on that address by asking the aquarium to assess the city’s primary climate risks while the city embarked on its own process of organizing town halls and community workshops and gathering input from scientific, academic, and business experts. The aquarium later issued a City of Long Beach Climate Resiliency Assessment Report in December of that year.

“No coastal community that I’m aware of is well prepared to deal with climate change,” Schubel, lead author of the climate resiliency assessment report, told Sierra. He estimates that by the end of the century, sea level rise could reach anywhere between three and six feet along much of the California coast. “We know it’s coming. We make a mistake when we look to 2100 and think that in the short-term we’ll be fine. We won’t. Every new report that comes out indicates it will rise more and more rapidly than the previous report.”

Among other findings, the aquarium’s assessment found that roughly 22,492 people in Long Beach are at risk from flooding during a 100-year storm, with that number increasing as sea levels rise. The assessment also made clear that extreme heat poses a significant risk to the city, a concern that Mayor Garcia considers particularly exigent.

“Sea level rise is obviously a concern, but it’s not the most immediate concern for us. The most immediate concern for us is rising temperatures,” Garcia told Sierra, “and just making sure that low-income folks and seniors and other members of our community that may not have access to a cooling center or air conditioning get the support they need.”

Last year the city unveiled a draft of its first-ever Climate Action and Adaptation Plan and is looking to release the final version sometime this summer. Some of the solutions under review involve addressing the city’s urban heat islands, where there is little natural protection from extreme temperatures in areas that lack landscaping or park space with tree canopies, and making sure schools and community centers have energy-efficient and low-to-zero technology. For sea level rise, the city is looking at permanent berms and other forms of ecosystem restoration work.

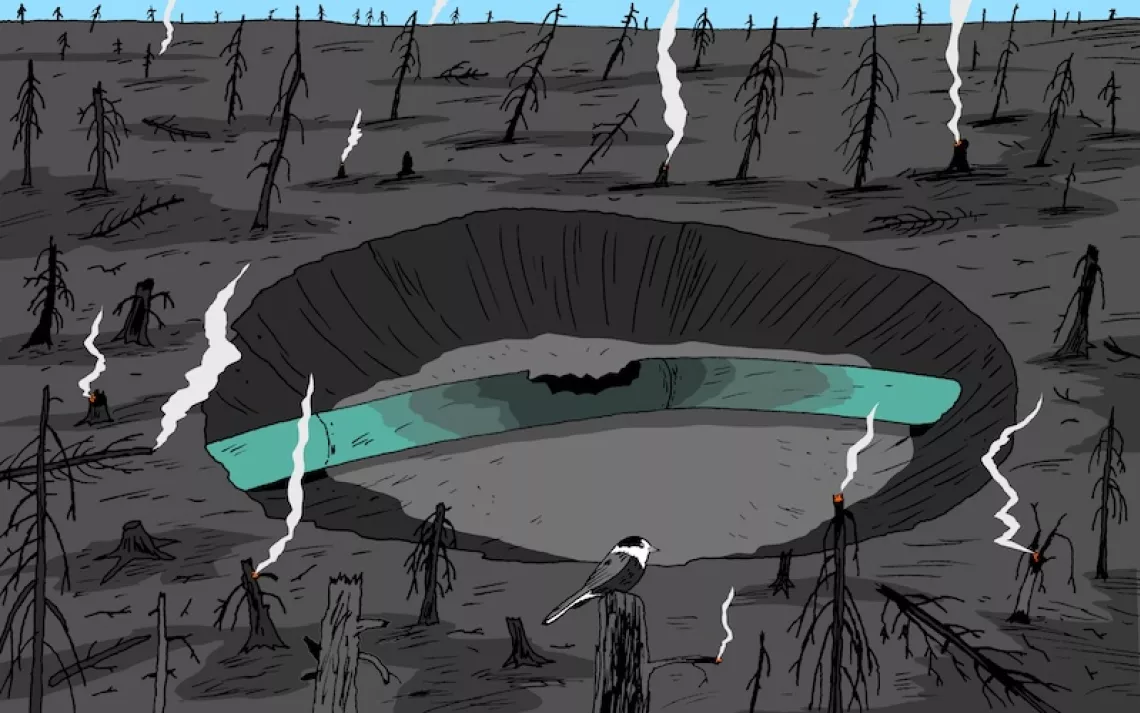

Residents at the March 9 workshop had the opportunity to engage with their city’s challenges through more than just statistical models and at times grim-looking charts. Dr. Juliano Calil, adjunct professor at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies in Monterey and cofounder of the climate virtual reality start-up Virtual Planet Technologies, has spent the past two years developing simulations of climate change impacts with a focus on sea level rise—the first for city managers in Santa Cruz, followed by another for the city of Long Beach. He made a handful of VR goggles available to attendees and this reporter at the workshop.

A rendering of the Santa Cruz virtual reality simulation, in which users can experience the progressive impact of sea level rise over time on the Santa Cruz Beach Boardwalk. | Courtesy of Virtual Planet Technologies

The simulation is a radically different way to experience climate change firsthand. After putting on the VR goggles, the user is dropped into an eerily real kind of library reading room, or den. With the touch of a button, one is transported onto a deck with a railing, beyond which the entire Long Beach coast extends for miles. With another click of a button, users can witness, in real time, coastal flooding and inundation along its contiguous neighborhoods.

The advantage of the experience, Calil said, is that people get more engaged, they tend to ask more questions, and it hits them in a completely more visceral way.

“2.3 billion people play video games of some sort,” he said, pointing out that he is a long-term gamer himself. “Creating a virtual reality experience can help people understand these issues. The bottom line is climate impacts are going to get worse. We have very limited resources, so we need to be really smart about how we make decisions and how we use those resources in a way that results in multiple benefits. Can you protect your wetlands that is going to protect a buffer to the neighborhood but also increase fisheries and habitation restoration? We’re just starting to explore how to display some of those ideas in virtual reality.”

Calil is now working with city managers in Paradise, California—the town in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada almost entirely destroyed by wildfires in November 2019—to do the same for their city, with a simulation that re-creates wildfire and also gives users an opportunity to explore mitigation and adaptation solutions for the future. “We don’t want to scare people,” he said. “That just does not work. We want to inspire them to get engaged.”

An afternoon breakout session gave residents the opportunity to pose their own solutions for sea level rise. Peter Hogensen, a retired aerospace engineer who moved to Long Beach in 1953, pressed his case for an extension to the breakwater that would enclose all of Long Beach harbor, similar to structures in the Netherlands.

Hogensen says part of the problem Long Beach faces is that residents aren’t accepting the gravity of their situation. “People are more focused on things in the immediate future, not the long term,” he said.

For residents in other coastal cities such as Del Mar, Pacifica, and Imperial Beach, conversations about sea level rise have collapsed before they could even get started at the mere mention of “managed retreat.” When residents in those communities were asked to evaluate managed retreat as among a suite of options they may have to face, opposition has been swift. Last year, Del Mar’s city council unanimously rejected 25 modifications that the California Coastal Commission proposed to its sea level adaptation plan. “We have managed retreat lurking between these words,” Councilwoman Terry Gaasterland stated of the commission's modifications.

How can coastal communities have a meaningful discussion about the situation they face, and the trade-offs of the various solutions available to them, without devolving into polarized either/or positions? Alyssa Mann says that the workshops and seminars they’ve hosted with the aquarium are designed to bring residents into the conversation and immerse them in the art of the possible, not just with engineering possibilities but through design and architecture and virtual reality. They’ve even organized a team of MBA students at CSU Long Beach to examine the financial implications of different proposals.

“In Long Beach we were seeing some of these same conversations happening, and so we wanted to come here and talk about this in a constructive way and bring a whole lot of perspectives in,” she says. “A lot of these decisions are going to be made at local levels. The state has a big role in directing guidance and funding. But ultimately, it’s local communities and the decisions they make that are going to be the difference here.”

“The purpose is not to scare people,” Mann said of the different educational tools on offer to residents at the workshops, such as Calil’s virtual reality simulations. “We’re trying to create a more realistic understanding of the issue and show the solutions of what might be possible. What we’re doing isn’t about the technology itself but highlighting how this immersive experience can be a powerful tool for engagement to lead to action on resilience, for both people and nature.”

Jerry Schubel hopes that these different ways of engaging the public with the problems of, and possible solutions to, climate change—everything from town halls and public workshops to virtual reality—will provide multiple lenses, both big and small, through which anyone can understand these issues more clearly and help the community move toward a sustainable path forward.

“We’re facing a crisis. But it’s different from other crises we’ve experienced,” he says. “It’s a crisis that has this enormous inertia built into it. Climate change is not an event. It sneaks up on you. This is going to play itself out over many decades and several centuries. We’ve never as a nation been very good with dealing with a crisis that comes out at you over a long period of time. Think about it: If I’m an elected official, it’s not going to happen while I’m in office. So it’s easy to kick the can down the road. Now, we’re beginning to see actions being taken, and we need all of those that we can."

“Managed retreat may very well be necessary at some point, but we have a number of decades to try to avoid that,” Schubel continued. “We don’t have to threaten people by saying that we have to retreat from the coast and begin to make those plans now. We need to be thinking creatively about ways we can keep people in their homes and businesses for a number of decades while we figure out what we’re going to do. In some areas of the state, retreating from the coast after you have major flooding makes sense if there are places to move to. But in much of California—Long Beach is one of those places—there isn’t any place to move. So we need to buy some time while we think our way through this.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club