Aya de León | Photo courtesy of Anna de León

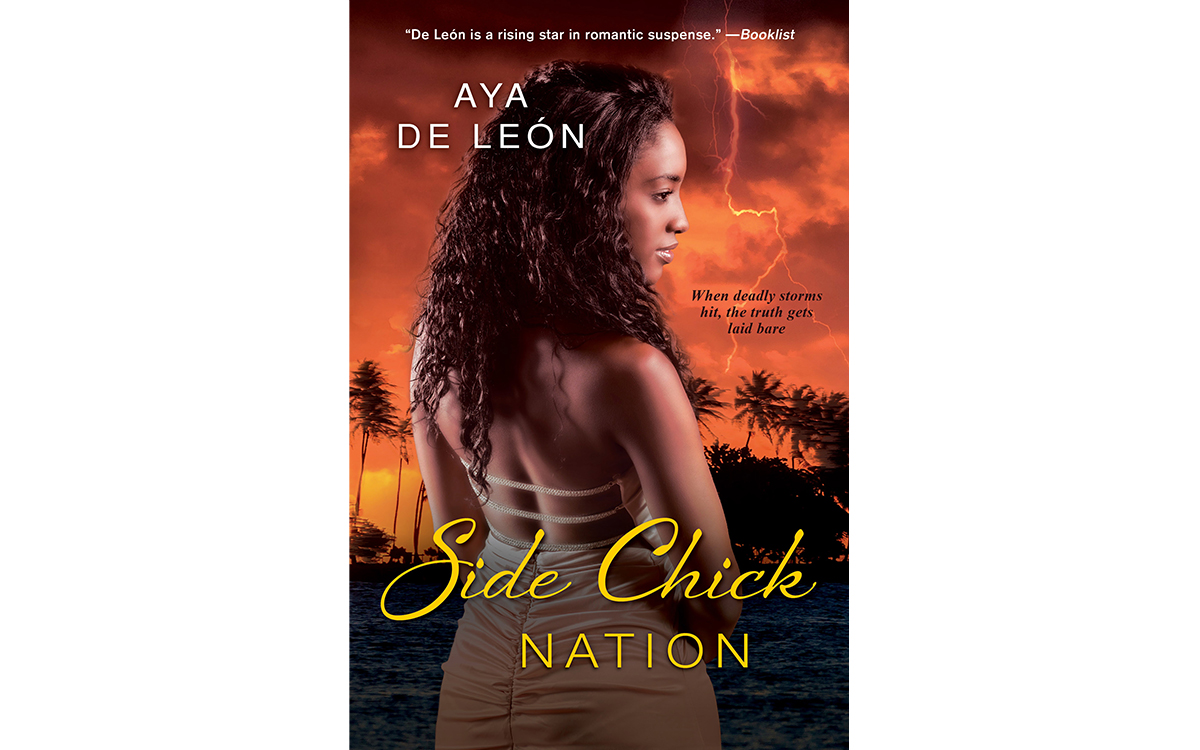

Side Chick Nation (Dafina/Kensington) is a romance novel about one of the worst climate disasters in US history. And what a novel it is. Bodices get ripped. Fancy clothes get bought. Luxury hotels get luxuriated in. Multiple men, in various degrees of hunky and rich, vie for the attention of the novel’s protagonist, a boy-crazy sex worker named Dulce Garcia.

Then Hurricane Maria hits the coast of Puerto Rico and things really get interesting, because the “side chick” in the title refers not just to Dulce, but to the 100+ years of history between Puerto Rico and the rest of the United States.

The author of Side Chick Nation, Aya de León, directs the Poetry for the People program at UC Berkeley, where she also teaches creative writing. We got the chance to talk recently about romance as a lens for viewing climate change, how to write about cultures you don’t completely understand, and how Naomi Klein got into that sex scene.

Sierra: So, you are an accomplished poet. How did you get into writing romantic heist novels?

Aya de León: My story is that I started out as a novelist in my early 20s. I'm extroverted, and I just didn't have the attention to write the kinds of novels that were in my head—so I started doing poetry and spoken word.

Then I matured, developed the capacity to sit down alone in a room and write for long periods of time, and started writing fiction. I had big ideas. I worked on a novel forever about black women in college fighting racism. I couldn't sell it. I still love that novel. One day that novel will see the light of day.

One day, an agent called me, and I said that I was also working on this sort of sex-worker heist novel. And the agent's assistant, she said, "Oh we'd really like to see that!"

I was like, "OK! I see this is more commercially viable." We know that sex sells. I became interested in how sex could also be really political. Sex work sits squarely at the intersection of gender, class, nationality, race, body, and commerce, so it has proven to be a great vehicle for me to take on lots and lots of different issues.

Did you get any pushback from your publisher about making your third book about Hurricane Maria? Were they like, "Doesn't sound very sexy!"

When the hurricane hit, I was working on a book that had already been sold. I said, "I want to write a book about the hurricane instead." My editor and publisher were fine with it. We knew that the news cycle of the hurricane would fade, and I really wanted the hurricane and its impact and aftermath and context to continue to be in people's faces long afterward.

Had you been to Puerto Rico?

My story is that my grandmother emigrated from Puerto Rico—I'm the second generation. My grandmother raised my mom as a widow for most of her life, and my mother raised me as a single mom. My parents divorced when I was really young. So even though my dad is African American and West Indian, culturally what I grew up with was mostly Puerto Rican, in terms of the underlying cultural content of my family.

So it's weird because on the one hand, I feel very Puerto Rican. But on the other, I didn't visit the island until I was in my early 20s. My mom didn't grow up speaking Spanish. I learned it in school. So it's this funny mix. I have the unspoken parts of the culture without having the obvious stuff like language and cooking.

I had lots of feelings about writing about the hurricane. I thought that maybe I'm not the right person to write it. But I was positioned such that I could. In that moment when all of us in the diaspora were like, "What can we do?," I thought, "Well, I'm a writer. What I do about things is I write about them.”

I did visit, eight months after the hurricane. I rented a car and drove around the interior of the island just to see what it looked like. There were still houses with trees that had crushed them. There were lots and lots of blue FEMA tarp roofs. The vegetation had come back in some places, but you could still see the absence of trees. I also read everything I could about the hurricane and worked with a sensitivity reader who had lived through the hurricane to vet my details.

What is a sensitivity reader?

Sensitivity readers are people who come from a particular community, whom writers can pay to read our work and tell us honestly, "I don't think this rings true."

People have been doing this for decades if not centuries—especially around gender. You hear all these stories of male writers who say, "My wife is my best editor.” And she's probably the one telling him, "Yeah women don't really think that. Women don't really act like that. That's unrealistic."

For each of my novels, I have a squad. I work with anywhere between three and five different sensitivity readers because I write about a really broad spectrum of things that are outside of my personal experience. I'm Puerto Rican. I'm also African American and West Indian. But my experience can be really different from my characters—I grew up on the West Coast, when my characters grew up on the East Coast.

I usually have someone in the sex work communities that I'm consulting with, to make sure that I'm representing them as realistically as possible because there's so much misinformation and distortion around their lives.

When I was working on my novel in the early 2000s, I was writing about male characters and convened some men to read it and said, "What do you guys think? Did I get it?" I was trying to do something about the emotional reality of this young black male character.

So what kind of feedback have you gotten about the book so far?

I got an initial Kirkus Review before the book came out that was positive, but then the romance reviewer for Kirkus read it and called it "must-read fiction." And she said something that I hadn't actually thought about, but it made perfect sense. She said there's something about the genre of romance with its promise of a happily-ever-after ending that allows people to look at things that are really hard—to look at tragedy and disaster.

I hadn't thought about it because I'm writing a series for a romance publisher where things are happily-ever-after. Those things were a given. But there's something about the contrast between this budding love between these two characters that creates this hopefulness within this horrible experience and allows the reader to stay with it.

It's not like that's all I write. Certainly, the book that I was working on with the women in college did not have a happily-ever-after romance ending. But that's part of this series, and I've committed to exploring the possibilities of that, particularly for people of color.

It's been interesting to think about, "Well what do I have to say about romance? Whose relationships do I want to work out?” People of color, particularly men and women, being able to love each other in spite of racism and all the patriarchal training that men have is good, you know? To be able to be kind to each other and have loving relationships—that's a positive thing.

Watching men triumph over choosing sexism and actually choose their partner is satisfying and something I like enough that I can write over and over again. And it’s something that I think readers like enough that they can read over and over again. It's triumph that we don't see enough of in the world, and that people have a pretty big appetite for.

I saw that Naomi Klein gave a positive review of the book, but I was wondering if she did that before or after she knew that there was a racy sex scene involving The Shock Doctrine?

I think she had read part of the book when she reviewed it. And then she read The Shock Doctrine scene and she thought, "Wow! Did not see that coming!"

Literally no one saw that coming.

It's the third sex scene between those two characters, and they are a couple that have been together a long time. So I'm always looking for something fun and interesting to play with in those sex scenes so that it's not just the same old thing. I read The Battle for Paradise when I was writing Side Chick Nation, and it was so important to me, but they couldn’t have been reading it in that scene because the book hadn’t come out yet.

Are there any other writers or journalists covering Puerto Rico right now that you would recommend to readers who want to learn more about what's happening now and what happened then?

Yes. Yarimar Bonilla. Rosa Clemente. Marisol Lebron. Rachel Richard. David Begnaud in the more mainstream realm. The Collectiva Feminista is really important in Puerto Rico. Latino Rebels is a great site.

These folks are talking about Puerto Rico in general. For me, it was critical to talk about it as a climate issue. I wanted to make sure that the words "climate change" were in the book and that it was also particularly about this one young woman—her journey from someone who was not thinking about it at all to someone who was then moving into activism around colonization and climate change and feminism.

Side Chick Nation has pushed me to respond to the climate emergency. My next book, which is actually going to be published next year, is about an FBI agent who infiltrates an African American eco-racial justice organization. The environment has always been on my radar, even though as a person of color there are challenges around racism in environmental movements. But this is the time to absolutely build a powerful coalition of our progressive movements. The solutions to racial and economic justice are also the solutions to climate change. It is critical right now for us to make working on climate solutions absolutely central.

I partly wrote this so that young women of color could begin to imagine themselves as part of a movement. They’re my core audience for this. And most writing about climate change is so post-apocalyptic. Those books need to happen too, but we also need, “Here’s how we fought and won.” We can’t indulge in despair.

Heather Smith is the former science editor at Sierra.

More articles by this author

- Keywords:

- books

- climate change