Could Las Vegas’s Grass Removal Policies Alter the Western US Drought-Scape?

Inside one of America’s most aggressive municipal water-conservation measures

Photo by Sean Pavone/iStock

The story of how Las Vegas became a leader in water conservation is driven, in part, by necessity. Not only is Nevada the driest state in the nation, but it also has a legal right to the smallest share of the Colorado River, a lifeline for much of the Southwest that supports about 40 million people.

That story starts in the 1990s. Developers were building. The population was about to spike—Las Vegas faced growing demands and a finite supply of water. The task of freeing up additional water fell to the Southern Nevada Water Authority, and the agency looked to expand its existing supply.

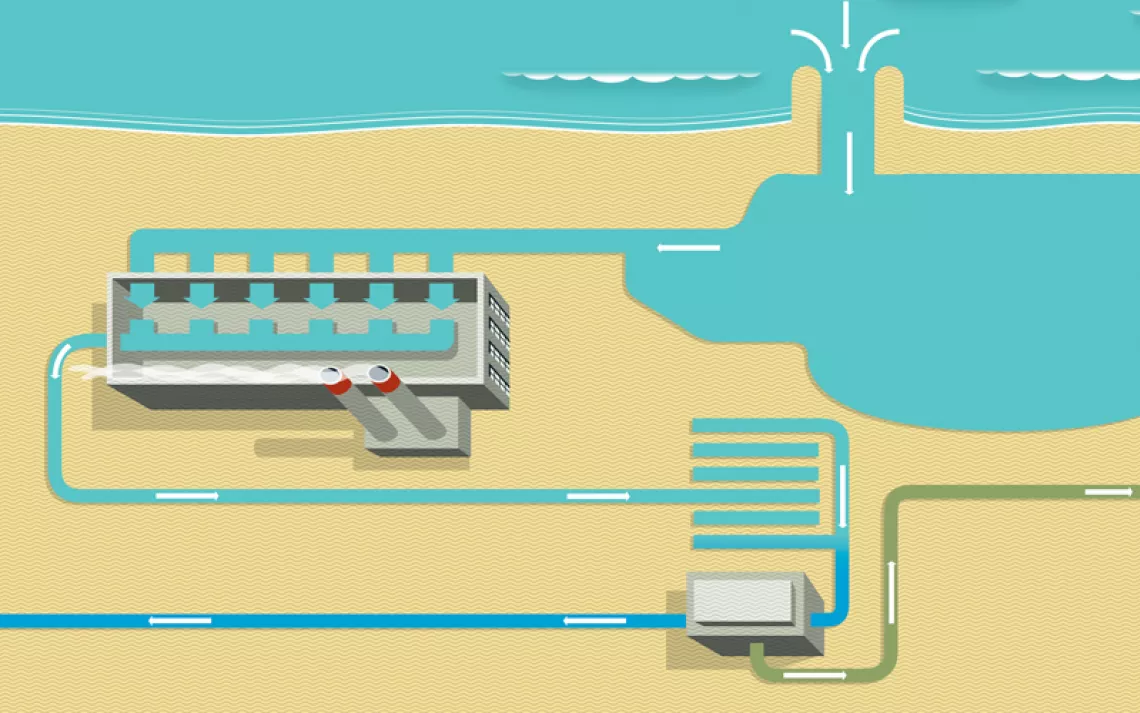

The water authority bought water on tributaries to the Colorado River, recycled indoor water to boost supplies, and pursued water rights across rural Nevada in a quest, eventually stymied by political fights, to pipe in new water. But eventually, and increasingly, it stretched its portfolio by simply using less.

The message to customers was clear: We need to reduce our per-capita water use.

With indoor water being recycled, the largest driver was outdoor use. Las Vegas set up a rebate program—“cash for grass”—to pay its customers to remove turf. The program has been wildly successful. Moreover, in a world where noncompulsory measures may no longer be enough, it was voluntary.

Earlier this year, the Nevada legislature made turf removal a requirement in cases where grass exists for purely aesthetic purposes. The legislation, pushed by the water authority and signed by Governor Steve Sisolak, requires the removal of all decorative, or “nonfunctional,” turf in Las Vegas by 2026. Under this law, residents can keep their lawns, and parks can keep their fields. But that turf decorating medians and buildings must be converted to less water-intensive vegetation.

Irrigating grass in the desert heat demands a lot of water. Ripping it out, on the other hand, will result in significant savings. The new law, according to water authority estimates, will save about 9.3 billion gallons annually, or nearly 10 percent of Nevada’s entire Colorado River allotment.

This makes the policy a significant marker for a Colorado River Basin facing prolonged drought and a drier future, fueled by the effects of warmer temperatures. John Entsminger, who leads the Southern Nevada Water Authority, recently described the new rule for Las Vegas as probably “the most aggressive municipal water conservation measure that's been taken in the western United States.”

Now, the question is whether other cities can do something similar. Because as climate change alters the water cycle for rivers across the West, many cities are facing population growth while looking at stable—or even shrinking—portfolios.

“An inevitable fact is we have to use less water,” said John Berggren, a policy analyst at the conservation group Western Resource Advocates. “For me, in the urban sector, nonfunctional turf is such a no-brainer for cities to reduce water use without making huge behavior changes.”

But when cities are looking at killing decorative grass, their methods might differ greatly. Some might send price signals, rather than rebates, to incentivize residents to rip out decorative grass. Others might focus on programs that encourage new developers, in search of water, to pay for the removal of grass.

The city of Phoenix, for instance, sends a price signal to customers by charging more for water in the summer. Kathryn Sorensen, a former director of Phoenix’s water utility, said that the rate structure has been “very effective” in getting customers to convert grass to desert landscaping. Sorensen said water use fell, at least in part, as more residents converted their lawns. According to the city, per-capita water use fell by 25 percent between 1994 and 2013, as Phoenix’s population grew.

“If you look at the municipal and private water provider context, the programs really vary, not just state to state, but literally water provider to water provider,” Sorensen said in an interview.

Drive across the Colorado River Basin, even from Las Vegas to Los Angeles, and this is evident just by observing what type of landscaping sits on the side of the freeway. But in some ways, Las Vegas has had structural advantages compared with other Southwestern states and water utilities.

The Southern Nevada Water Authority is a single entity, governed by local elected officials, that manages the state’s Colorado River supply and provides water to more than 70 percent of the state’s population. The water authority has been able to set aside funding to pursue a turf rebate program.

In other western states—like Arizona, California, Colorado, and Utah—decision-making is more diffuse. Even in Nevada, the turf removal requirement did not apply to Reno, where the local water provider says there is no funding for a turf rebate. Resources vary from water district to water district. Some have funds to provide turf rebates. Others might need to get more creative about how they pay for grass conversion.

Carol Ward, a deputy assistant director for water planning and permitting at the Arizona Department of Water Resources, has spent her career encouraging municipal conservation in Arizona. She said that today, most communities in the Phoenix metropolitan area have incentives to rip out existing grass. But there is another side to it: Education and community buy-in are needed to change the culture. “We've really focused on changing people's expectations—the cultural norms,” she said.

Ward previously worked with the Arizona Municipal Water Users Association. She said that back in the 1980s, the nonprofit recognized the need to showcase desert landscaping; specifically, how it could replace grass. The group published brochures and resources. Like Las Vegas, cities sought buy-in from business interests. So the group, along with Tucson Water and the University of Arizona Cooperative Extension, helped to launch a training program for landscaping experts.

The challenge today, as Ward said, is that “as you go, the harder it is to get that turf removed.” What she means is that, within western cities that have pushed for its removal, a lot of existing decorative turf covers ground in hard-to-reach places—at complexes and in neighborhoods where HOAs are reluctant to remove it, for instance, or on odd strips of land within commercial centers. Such limitations were drivers in why Las Vegas earlier this year pursued a requirement, rather than rely on more voluntary measures.

Although western water districts vary in structure, many providers face the same challenge: There are few sources of unclaimed water, and in many cases, the pie—the amount of water flowing downriver—is shrinking even as cities continue to expand. Some water managers will have to support more people with a fixed supply. Which makes grass a prime target for reducing use.

The predicament that caused Las Vegas to act early is now true of many cities. Yes, replacing turf can be expensive. But in a reality where communities need to do more with the same amount of water, Berggren said reducing demand should be a first priority.

This is especially true for water providers who are pursuing new supplies and diversions that could add more strain to the Colorado River and the Southwest’s water issues. Most notably, Utah officials have continued to pursue the permitting of a project that would divert significant amounts of Colorado River water about 140 miles, from Lake Powell to southern Utah.

More progressive conservation programs—such as one to convert turf in Utah—could eliminate the need for the so-called Lake Powell Pipeline, environmentalists have argued. Nevada officials made a similar suggestion in a comment letter last year, asking officials to consider additional conservation measures.

Berggren said it’s important to make the case that turf removal can pay for itself—at least in the long run. Because the cost of new diversions is high. And according to Berggren, this is starting to happen. He said cities are increasingly viewing grass conversion as an alternative to bolster water supplies. If cities can incorporate turf removal into capital investment plans, he said, it is “much cheaper than going out to secure new supplies.”

Berggren explained, “That’s the calculation that a lot of communities are making.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club