Island in the Storm

A letter from St. Vincent National Wildlife Refuge on the eve of Hurricane Michael

Damaged homes are seen along the water's edge in the aftermath of Hurricane Michael in Mexico Beach, Florida, on October 12, 2018. | Photo by AP Photo/David Goldman

It is noon on Wednesday, October 10. The eye-wall of Hurricane Michael has neared the Florida coast, with an estimated wind speed of 150 miles per hour, a Class 4 hurricane. At our home in Tallahassee, my husband, Jeff, has filled the freezer with extra ice and readied a small generator in the carport. While we still have power, I make sandwiches for our lunch and dinner and carefully wash the breakfast dishes.

I’ve got little middens of storm prep materials scattered about the house, should we decide to bolt. On my dresser, a small toiletry bag with toothbrush and Ambien, a pocket flashlight, and Anne Hillerman’s new novel. On my desk, a laptop, my journal, and Blue Nights by Joan Didion. By the front door, we’ve collected a sheaf of insurance documents, three solar lanterns, and a carrier for our cat.

As we always do in the hours before a tropical weather event, we have walked from one neighbor’s house to the next, checking in and discussing which interior rooms might be best to sit in and shelter from the storm, as the winds shift over the course of the day from east to southeast to southwest.

*

Four days earlier, we did the same kind of safety check on the island we love above all other places on Earth—St. Vincent, a 12,000-acre island protected as a national wildlife refuge since 1968, which sits atop the trailing margin of northwest Florida’s gulf coast. It is 100 miles west of Tallahassee and 25 miles from where the eye of Michael would eventually come ashore. We are faithful to this island, have loved it and cared for it for more than two decades. Used to be, we’d come just to camp and kayak, but more and more often, we pitch in with trash cleanups, raise money for the refuge, and help with sea turtle patrol. I participate in Christmas and Breeding Shorebird counts and have even written a book about the island. My husband and I lead nature walks and mark eagle-nesting territories; Jeff is measuring the erosion of the island’s coastline with simple posts and complicated survey equipment.

So when we got word of the storm, we touched in by boat and on foot with what we know to be the most vulnerable of the island’s geographies.

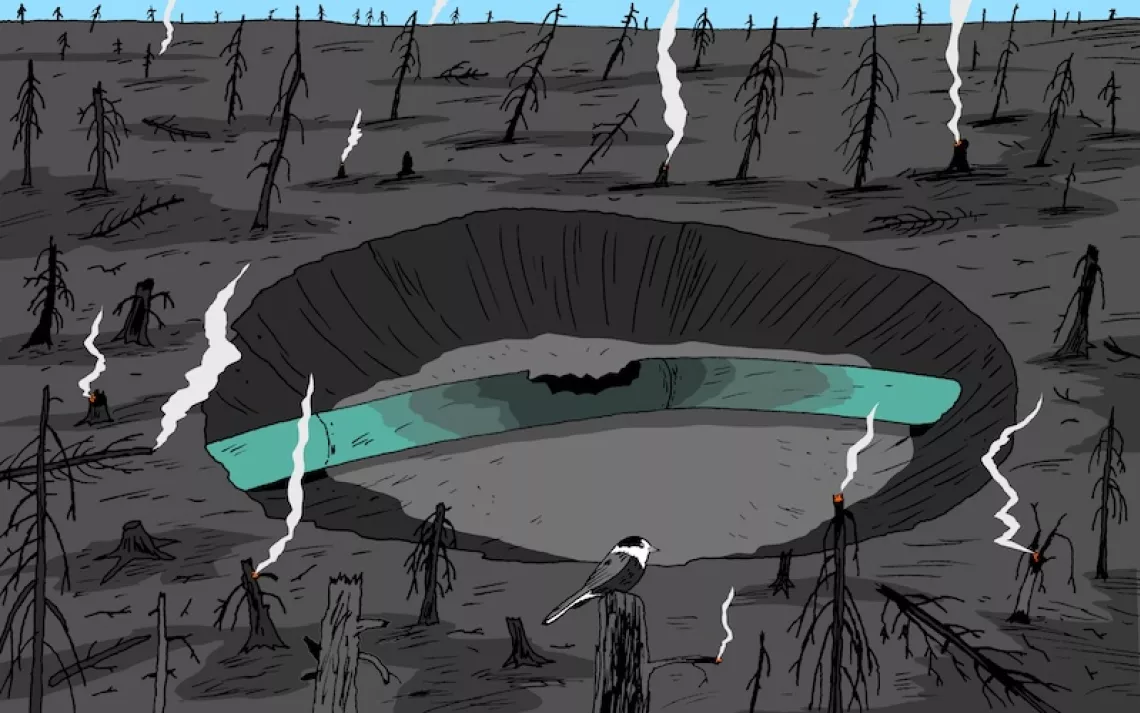

What we found: the island is doing its level best to survive in our warming, rising-sea world. Still, out on the gulf front, near the beach-nesting bald eagles, 800-year-old foredunes are retreating at an alarming pace. You can see how the waves are biting into sand layers that haven’t been exposed since the sea first laid them down, how they slump and collapse on the narrowing strand. Yet the roots of the palms and pines are still working as leashes, cords, and powerful nets and fingers; for now, at least, they continue to hold the sand in place. If they succeed, the rest of life on the island may live. At the peak of the eroding dune, migrating butterflies (Gulf fritillary, sulfur, and long-tailed skipper) take nectar from the small flowers of sandspur and purple blazing star. Like the sea oats and the sandspurs and the pines and the palms and the butterflies, I cling to the island with all my being, offering it my fullest attention. It is an urgent and curiously satisfying pursuit, to witness in this way. On the island, I am so very present that I cannot dwell on what may come, including all that the Trump administration is dismantling and poisoning.

At Cabbage Top, the oldest beach ridge on the island’s north-facing side, few living palms still remain, and I think I found the very last of the beautiful Christmas berry shrubs, giving way to tide.

There’s better news at St. Vincent Point: Brown pelicans have had a robust nesting season this summer in Apalachicola Bay. I tallied more than 600 resting there, three days in a row.

At Sheepshead spit, we anchored our boat on the lee side of the wind. It was two days before the new moon tide, what we call “king” because of its power to raise the sea. We were astounded to see how that sand-over-oystershell ridge had lost ground, well in advance of this one storm.

The spit extends half a mile from Dry Bar to a small drumstick of sand where a pair of oystercatchers lives. That narrow berm offers a trail for every kind of mammal that resides on the island. I have seen their footsteps, single file, how they press the black needle rush and bits of plastic and ancient pottery shards into a path. Tracks of sambar deer, footprints of red wolf, raccoon, river otter, and feral hog. Tail drags of alligator, slipping from salt marsh to gulf and back again, perpendicular to the linear trail of the mammals. There used to be the tire marks of the refuge staff’s ATV, too, when the spit was still wide enough to drive on. This is the end of the road, and everyone likes to visit.

Last May, at the end of that spit, I found a staggering 60 nesting pairs of least terns, along with two wary American oystercatchers. The terns divebombed me, threatened to puncture my scalp with their sharp beaks, to keep me back from their eggs. But I wasn’t their problem. It was my species, my carbon-spewing, human species that was warming and rising the waters. Just days after my visit, Tropical Storm Alberto swept every one of those nests to sea. From Cape San Blas to Indian Pass, tourists retrieved those drowned beautiful eggs along many miles of mainland wrack and dune.

Now, two days before high tide and Hurricane Michael’s landfall, the water is already sloshing over the pink feet and fleshy shins of the oystercatchers. They remain faithful to Sheepshead, but where will they go when it washes away?

Photo courtesy of Susan Cerulean

*

“We’ve never had a Cat 4 hit the panhandle coast before!” The weather forecasters on our television screen burst with facts and flourish. “An October hurricane is something our coast hasn’t seen since the 1950s!”

But it isn’t their coast. The water streaming over their boots is not their water, the Apalachicola River and the gulf are not water bodies they know. I am angry watching them stand in front of national cameras on Apalachicola’s Water Street, tide running over their feet. They don’t know, as we do, the context of this place so at risk, even as they exhort messages of doom. The TV reporters from far away don’t know where the trawlers and oyster boats missing from camera view have sheltered from the storm. They don’t know that right behind them is Café con Leche, the beating heart of Apalachicola, and the office of the Apalachicola Riverkeepers, and the Grady Market. They don’t know how our islands are eroding into the sea.

The weather people seem to me like temporary coyotes descended upon our town, cavorting and courting danger, while real people’s lives and livelihoods hang in the balance.

And the forecasters almost never connect the dots for their viewers: that this storm, with all its superlatives, is itself fed by the rapid human-induced warming of our globe.

But I am far angrier at our senator, Marco Rubio, the Florida Republican, who also comes on the screen, urging us to “be safe” and “find shelter.”

He whines. He just can’t understand. Why won’t people listen when he tells them to evacuate?

“What about the irony of your posturings don’t you understand, Marco?” I yell at the TV.

I say, “We can’t understand why you won’t listen when we tell you what is really happening.”

His bland smile tells me he doesn’t understand me, and never will.

Before the power blows, though, I have the last word: “Oh yeah, Marco, I forgot. You and your ilk are getting rich off all this.”

*

We watch the progress of the storm on television until electrical transformers begin to pop like guns and the lights flicker and go out for good. Then we turn to the real nature channel, the one just outside, and spend the rest of the storm on our front screen porch.

A pair of cardinals scud from the cabbage palm to the satsuma orange at the edge of the yard. The tops of the trees are crazy immersion blenders, stirred by the invisible wind. Rain intensifies. The cardinals, of course, are staying. They have no other choice. I guess we are, too, although Jeff says we should put on our socks and shoes in case we need to run. This strikes me funny, because I can’t imagine where we would go. The trees are bending for their lives, and my heart beats hard for them and for me.

By mid-afternoon, the winds are clocking up to 70 mph right on our little street, blowing south to north. They knock the top out of an ash tree 20 feet from where we sit and hurl it into the grass. The air (this carbon-laden atmosphere) is steamy and condenses on our skin.

The eye of the hurricane moves to the north of us, and the winds shift west-south-west. Gusts still rage high and scary, and we can tell the wind direction by the sheets of leaves and sweet gum balls, forced tree to ground, tree to ground.

Photo courtesy of Susan Cerulean

*

I like to tell people, as they sit on St. Vincent’s gulf beach, that when you dig your fingers into that sand, you hold the bodies of mountains in your hands. I like to see their eyes unfocus as they feel how those peaks tumbled into granules of quartz and feldspar, and know that their minds are expanding to take in geological time.

Geological time is what we must begin to understand. Sixteen days ago, Jeff, a professor at Florida State University, gave an invited talk called “Climate and Sea Level: 50 Million Years of Climate History.” The theater at the Challenger Center in Tallahassee was nearly filled with local scientists and activists, and we’d also invited friends who hadn’t before heard Jeff’s rap. Between us, Jeff and I have given hundreds of readings and talks, PowerPoints, classes and scientific presentations on the subject of climate change in Florida. In the summer of 2014, Jeff and a cadre of four other scientists wangled 30 minutes of face time with Governor “Red Tide” Rick Scott, hoping to open his mind about the effects of rapid impending climate change and sea level rise in Florida. Scott, a Republican, is the governor who had previously prohibited the use of the phrase “climate change” by state employees.

Our next-door neighbors, a retired highway patrol officer and his wife, were here for this talk, and so was my best friend’s new girlfriend. I watched my dear friend Rosi climb high up the auditorium steps with her 23-year-old son. Rosi is a full-time lawyer, a single mom, and many evenings, we sing together in a trio for patients in hospice. Our massage therapist, Sarah, sat beside me. Sarah has auburn, shoulder-length hair and an unbounded can-do optimism. She supports three children, a grandson, a small dog, and, intermittently, backyard chickens on her small healer’s income.

Why place this burden of knowledge on Sarah and Rosi and all the rest? I am always so proud of Jeff’s oratory skill, and his humor, despite the terrifying nature of his story. But I shifted in the cushy theater seat as he spoke, wondering how our friends would feel, learning what kind of superheated world their children face.

After Jeff’s talk, Rosi’s son said to his mother, “I knew it was happening—climate change—but I didn’t know it was coming so fast.”

He was right. Climate change is coming very fast, indeed—at hurricane-force speed.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club