In Puerto Rico, a Call for Climate Justice, and Social Justice Too

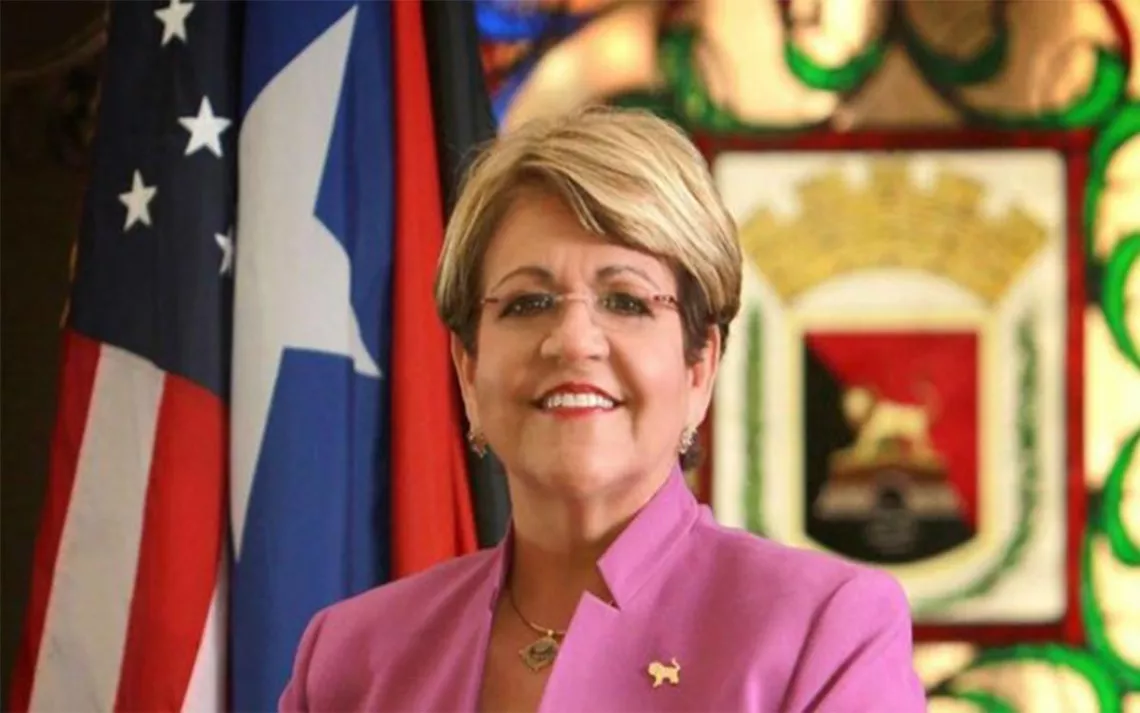

Mayor María Meléndez says it’s all about public service

Photos courtesy of María Meléndez

María Meléndez always saw her career as a dental surgeon as a form of public service—a way of giving back to friends and neighbors in need. She grew up in Bayamón, Puerto Rico, where her father modeled the importance of service early on: He often hosted local politicians in basement salons to talk island politics and work through the issues of the day.

Those childhood memories helped shape her conviction that civic engagement and public discourse are the lifeblood of a healthy body politic, and as such, citizens should look for any opportunity to get involved in public life. That’s why, after 31 years, Meléndez walked away from her dental practice in Ponce, the second-largest city in Puerto Rico, and took on a new ambition: to be that city’s first-ever female mayor.

“We need more women to work in politics,” she told Sierra while in Washington, D.C., recently to press for more support as Puerto Rico struggles to rebuild one year after Hurricane Maria. “It’s important that we participate not only in politics but also in problem-solving for the community.”

In the nearly 10 years since Meléndez took office, she’s had to contend with the island’s spiraling debt crisis and deteriorating infrastructure while she tries to nurture economic opportunity and tourism growth in her city, all while remaining a staunch advocate for statehood. (Puerto Rico is a United States territory and its people are U.S. citizens, but without voting rights or representation in Congress.)

She’s also been a vocal proponent of getting more women into politics: Of Puerto Rico’s 78 cities, only seven have female mayors.

But nothing comes close to the challenge of leading Ponce in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria, the most devastating natural disaster to ever strike the island. Electricity was restored to all of Ponce just three months ago. There are an estimated 1,077 homes in the city still without roofs. Approximately 440 municipal structures were damaged in Ponce during Hurricane Maria. The island’s Department of Housing administers funds from the U.S. Community Development Block Grant–Disaster Recovery Program for disaster recovery projects like reconstructing buildings and roads, but those projects have stalled as the disbursement of the funds has moved at a glacial pace.

The cost of reconstruction in the municipality is projected to top $200 million at least. The estimate of the first of 10 FEMA-related projects is just around $45 million.

Meléndez, who also goes by “Mayita,”says that after a year-long electricity crisis across the island, the whole utility system has to be rebuilt, and the starting point for that process needs to be clean energy. She has been forging alliances with other U.S. mayors such as Eric Garcetti in Los Angeles and LaToya Cantrell of New Orleans to help glean ideas for how to best proceed with revamping the energy grid to make it not just functional but resilient and renewable.

But little has been done to move these huge infrastructure projects forward. That’s a constant source of frustration, Meléndez says, for residents who already feel like they are being treated as second-class citizens—especially given the Trump administration’s slapdash response to Hurricane Maria, compared to how the administration handled other climate-related disasters on the mainland. For example, within six days of Hurricane Harvey making landfall in Texas, 73 helicopters deployed for rescue operations. It took three weeks for as many helicopters to deploy to Puerto Rico. FEMA approved $141.8 million for victims of Hurricane Harvey in Texas less than two weeks after the hurricane hit. In Puerto Rico, nine days after Maria made landfall, only $6 million was approved.

That makes the Trump administration’s response to the devastation in Puerto Rico a civil rights issue, not simply a climate issue, Meléndez says.

“We need to be treated equally the way they treat California, the way they treat Florida, the way they treat Texas,” she says. “And we are American citizens. We are a territory, but we are American citizens.”

Meléndez has no illusions about the challenge the island faces: It took more than 13 years to rebuild New Orleans after Katrina. But when she thinks about her two daughters, both of whom are lawyers (one works in the island’s House of Representatives), and her grandchildren, the stakes for reconstruction are far greater than simply rebuilding the old system back to what it was. Meléndez speaks with emotion about how her seven-year-old granddaughter held on to her for three weeks after Maria hit the island, and didn’t want to let go.

“Climate change is a reality,” she says. “The future of our children, our grandchildren, is now. It is not a game. We only have 12 years to address it according to the latest IPCC report. We have to take action, not just for ourselves but for future generations. We need more clean energy. We need no more petroleum. We have to be conscious in how we make public policy. We only have 12 years to undo the damage that has been done to the environment.”

The best way for people to participate in that process, Melendez says, is to get active and get involved; to find out how you can use your skills for public service.

“For 31 years I served the people as a dentist,” she says. “Now I serve the people through politics. That’s what I love to do.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club