One Infinitely Beautiful Planet Earth

Astronaut Chris Hadfield’s photography is literally out of this world

Photos by Chris Hadfield | Courtesy of National Geographic

Of all the words in the pages of books, newspapers, and magazines you’ve read, which was your favorite?

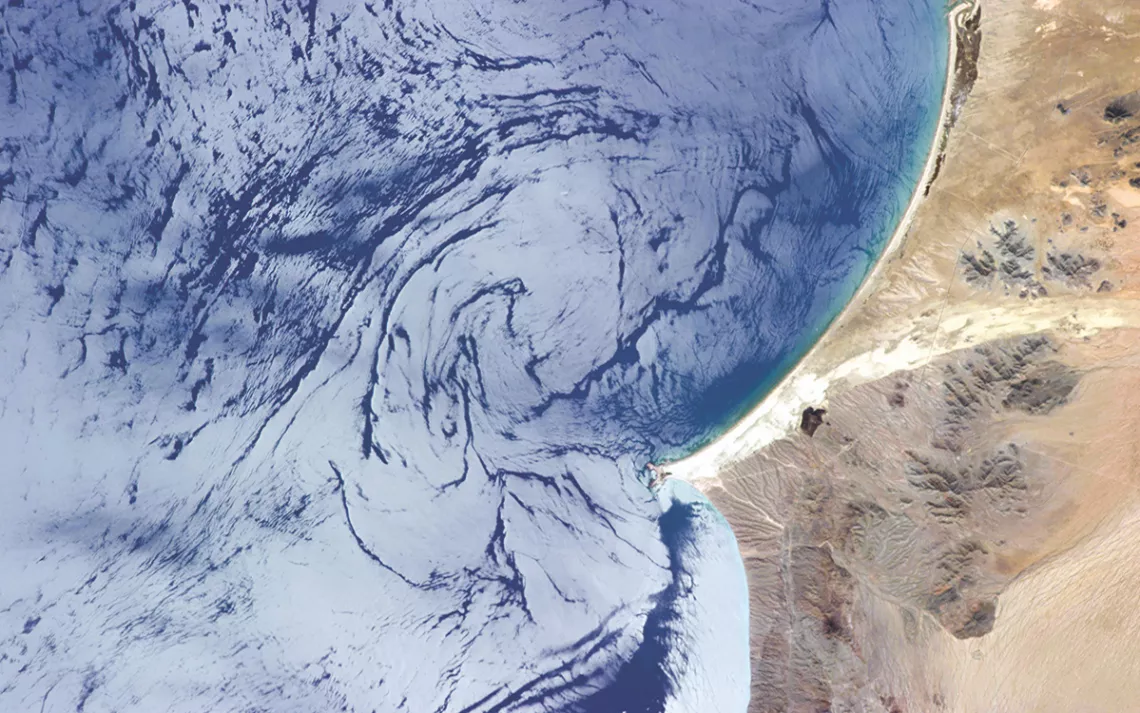

As preposterous an exercise as answering that question might seem, just imagine what it would be like to take thousands of photographs of Earth from outer space and then have to decide on a favorite. Chances are it would be impossible—writ large in all its depth and span, the ancient, regenerative nature of our world, and the truth of the commonality of the human experience, would be incontrovertible in every shot.

For Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield, capturing that truth in pictures and video for all earthlings to see is as much a part of his mission as scientific experiments and exploration. Over the course of three space flights, 4,000 hours in space, and 2,600 orbits of Earth, Hadfield—the first Canadian astronaut to command the International Space Station (ISS)—has taken approximately 45,000 pictures of the planet we call home.

“There is not one second in your day in six months on a space station where anybody ever says to you, ‘Go take pictures now,’” Hadfield said in an interview. “The assumption is always that we will steal time, we’ll stay up when we’re supposed to be asleep, we’ll try to get ahead of schedule just so we don’t miss it—that incredible view. We are the photographers for the world, the few of us up there. We take the responsibility very seriously, and do our absolute best to have both the technical competence and an artistic eye to truly share where we are.”

Hadfield is one of eight elite astronauts who anchor National Geographic’s 10-part series One Strange Rock (Nutopia; Protozoa Pictures). Vanguard filmmaker Darren Aronofsky teamed up with an all-star cast of co-executive producers, including Jane Root and Ari Handel, to deliver a cinematic spectacle unlike anything you’ve ever seen on television (click here for a full review). Hosted by Will Smith, each of the series’ 10 episodes is dedicated to a different aspect of what makes Planet Earth so peculiar, and so extraordinary—whether it be the source of the oxygen we breathe or the chance conditions that came together to make life possible (the next episode in the series is scheduled to air on Monday, April 30). Each episode is presented by astronauts with a combined 1,000 days in space between them: Chris Hadfield, Jeff Hoffman, Mae Jemison, Jerry Linenger, Mike Massimino, Leland Melvin, Nocle Stott, and Peggy Whitson. Through their eyes, we see and experience the chance and pure wonder of the universe’s greatest space oddity: us.

What in part makes One Strange Rock so compelling is dazzling video and photography covering 45 countries on six continents, some of it shot from the vantage point of outer space. Several of those out-of-this-world photos were taken by Hadfield.

Hadfield’s 21 years of training to be an astronaut included working with professional photographers to master all forms of the medium. Over three space flights, he took imagery with Hasselblad film and Hasselblad digital, 35mm film, 35mm digital with a whole selection of lenses, and helped make two IMAX films while he was at it. Astronauts are trained in everything from medicine and science to public speaking, multiple languages, and all forms of media. They have to be as skilled at conducting scientific experiments in zero gravity as they are at communicating what they are seeing and experiencing to the world.

“Photography is an important part of space flight in that it allows you to share a perspective, and it also gives you one of the better ways to try and capture what’s happening,” Hadfield says. “It is so overwhelmingly sensory and sensually stimulating to be weightless and to be going around the planet every 92 minutes and to see everything, all day and every day—to see this enormous human creation. It’s a cornucopia of constant ideas.”

Photography is just one of the ways Hadfield has tried to capture that visual array. He is also a musician who became a YouTube sensation when he recorded the first-ever music video performed in space—a rendition of David Bowie’s Space Oddity, which has received nearly 40 million views to date.

He’s written three books, including a collection of his otherworldly photography (You Are Here: Around the World in 92 Minutes: Photographs From the International Space Station) for which he had the unenviable task of trying to distill the thousands of epic photos he's taken of Earth into a selection of just 150. The only way he could think to go about the task, he says, is to imagine what he would want to show to an everyday earthling if he had the chance to bring one of us up with him into orbit. "I thought, if I could bring someone like you on board and we had one trip around the world together and get 90 minutes at the window, what would I want to show you? What makes me laugh? What makes me gasp? What makes me think? What makes me despair? When you see the whole world in an hour and a half, what do you truly get from it?"

Taking professional-level photographs can be hard enough while standing right here on Earth. Imagine trying to do it without gravity, free-floating in the inky black of space. No simple task, but Hadfield says he faced many of the same obstacles that any photographer does.

“The most important thing in a good photograph is light,” he says casually, as if talking about the best way to take shots of a stand of trees in a park, or a beach scene on a Sunday afternoon. “Our lighting is so harsh; there is no foreground normally. The lighting is perfectly black when you stare into space and brilliantly reflected off of Earth, especially the lighter-shade parts of Earth, the clouds, the snow. To try and properly expose things and get them properly lit is an eternal challenge. Trying to take pictures during a space walk is especially bad because the seats are pure pristine white, and the space station is gold and silver and metallic, and space is a bottomless velvety blackness.”

Nevertheless, weightlessness is still a unique challenge when it comes to taking pictures from outer space. You can’t just plant your feet and use a tripod to be properly positioned and still. You are perpetually floating in motion, so to frame and take a picture takes some planning.

“Your body pulses with your heartbeat and your breathing,” Hadfield says. “There’s no gravity to make you feel stable. Each pulse of your heart moves your arms and your hands very slightly, because you’re like a big balloon. There’s no gravity to overpower the effect of the blood actually being pumped through you. So you have to take pictures in between heartbeats if you want to take a picture with any sensitivity.”

With the world going by at a rate of five miles a second, it can also be difficult to avoid blurry shots, especially in low light, or in dusk while traveling on the dark side of the world.

“You cross the United States in nine minutes, so it takes a lot of planning to take a photo of a specific location,” Hadfield says. “If you want to take a good picture of the L.A. Basin, you need to start getting your camera ready over Hawaii, because it’ll take that long just to get into position, to get your body braced, the right selection of lenses, the memory card in the camera, all the proper F-stop and everything set, syncing to the lighting of the day, then frame, focus, and fire with maybe 20 seconds over Los Angeles before you’re already spitting out into the desert and looking ahead to Phoenix and beyond."

The lighting inside a spaceship is like the lighting in a drab office, Hadfield says, with the added fact that you are essentially inside a long tube that doesn’t lend itself to good three-dimensional photos. Of course, photography for astronauts is not all pretty pictures. Many of the experiments on the International Space Station require photography, whether through telescopes, microscopes, or other instruments.

The vast majority of the shots astronauts take of Earth while at the space station is through glass. The station has a huge multipaned window shaped like a cupola where the astronauts go to document the world.

“You can look forward to where you’re going. You can look to where you’ve been,” Hadfield says describing what it’s like to peer out from the cupola. “You can look left and right and most importantly, straight down at Earth. Oddly enough, if feels like you’re looking up at Earth. It feels intuitively like the world is above you, not below you.”

In spite of how many times he circumnavigates our planet, and all that training and preparation, Hadfield says the view could never possibly get old. In fact, the world as it appears outside that window at one moment is never the same at the next. The angle of the sun constantly changes because they are going at a speed of 17,000 miles an hour. The shadows change. The world itself changes constantly because of weather, and then it changes gradually because of the seasons. Every time he positions himself in front of the cupola with his camera, Hadfield says, he sees our world, brand new, all over again. "The world is infinitely beautiful.”

“I was on the spaceship as we went from one side of the solar system to the other,” Hadfield says. “I watched the world swap from winter to summer as if the whole planet just took one breath in a 4½-billion-year history of breathing. Every time you come around, you get better at seeing it, and learn where to look—and your pictures become more intimate with the world."

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club