This Year’s Polar Bear Week Matters More Than Ever

The annual event brings us cute videos and an important message

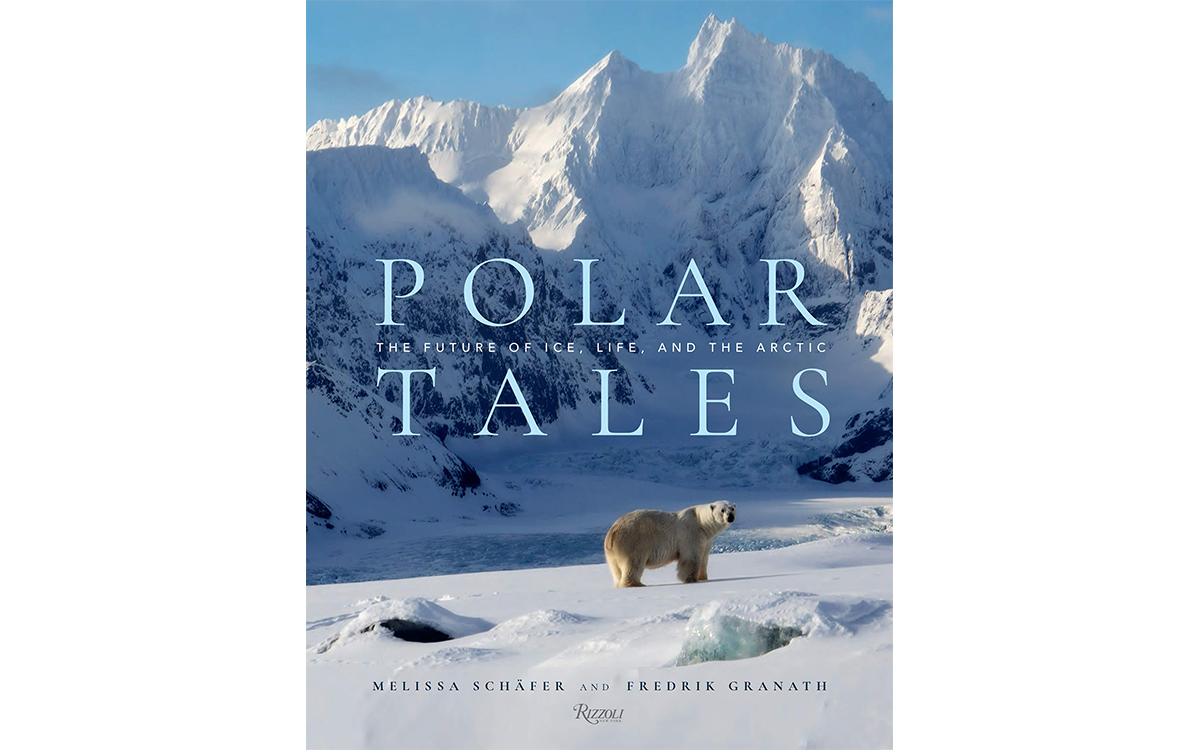

Photos by Melissa Schäfer

Churchill, Canada, quickly becomes the world’s polar bear capital each fall as the animals pass through en route to newly formed ice, wowing tourists in the process. On schedule with the annual migration, the conservation nonprofit Polar Bears International has planned its Polar Bear Week 2020 for this November 1 to 7. By sharing live migration feeds and online lectures, the organization encourages climate solutions to preserve the polar bear’s Arctic home.

This year’s Polar Bear Week arrives shortly after a grave finding: Unless we drastically curb greenhouse gas emissions, we could lose most of the world’s polar bears by 2100. Dwindling sea ice disrupts the creatures’ hunt for seals and therefore jeopardizes reproduction and survival rates, according to a July 2020 study published in Nature Climate Change.

For most of us living thousands of miles from the Arctic, it’s difficult to visualize these losses. To illuminate the accelerating struggle of animals that depend on now-melting ice caps, photographer-producer duo Melissa Schäfer and Fredrik Granath spent half a decade working in Norway’s Svalbard archipelago for their new book, Polar Tales: The Future of Ice, Life, and the Arctic.

While shooting Polar Tales, Schäfer and Granath say they observed firsthand the sobering impacts of rising temperatures. One spring, they encountered a thin-looking bear isolated on an island with little to eat. The surrounding ice had melted too early and already drifted around 60 miles, Schäfer says, meaning that it’d be nearly eight months before the bear could travel again for food. “We couldn’t do anything,” Schäfer says. “It just broke my heart to know that he will probably die there because there’s no ice and no food.”

This scene has become increasingly common as the polar bear’s habitat rapidly disappears. Last September, scientists announced that 2020 marked the second-lowest Arctic sea ice level on record. Significant melting began in the late 1970s—since then, the ice has decreased by 40 percent. Now, the ice that expands during the winter is thinner than in the past.

In addition to diminishing sea ice, polar bears also face a substantial threat from the oil industry. When companies send equipment to survey potential Arctic reserves, they risk crushing the polar bear dens hidden underneath. Though specialized infrared cameras are meant to protect these dens, a February 2020 study found that this method is often ineffective.

Employing the same fickle technology, the Trump administration proposes surveying Alaska’s Arctic National Wildlife Refuge this December. In the country’s largest remaining wilderness area, the southern Beaufort Sea polar bears are already highly vulnerable: The population has dropped by nearly half since the 1980s. The US Geological Survey found that oil and gas drilling could disturb polar bear reproduction within the refuge, but director James Reilly refused to make the study public.

But there is some good news on the conservation front. Researchers have adapted a military radar system to detect polar bears and warn Arctic communities while they’re still distant. A joint effort by Polar Bears International and York University, the “BEARDAR” could help wildlife managers drive the creatures away from areas where humans live without killing them. It’s currently being used in Churchill, where the fall migration has already begun.

With live cameras and close-range photos of polar bears in their threatened environments, even those far removed from the Arctic can get a close-up look. This matters as we fight to protect these animals and their declining habitats, Granath says.

“Nature has become abstract for many people,” he says. “What we and all the other great nature photographers are trying to do is shorten the distance, to make people reconnect with what is important.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club