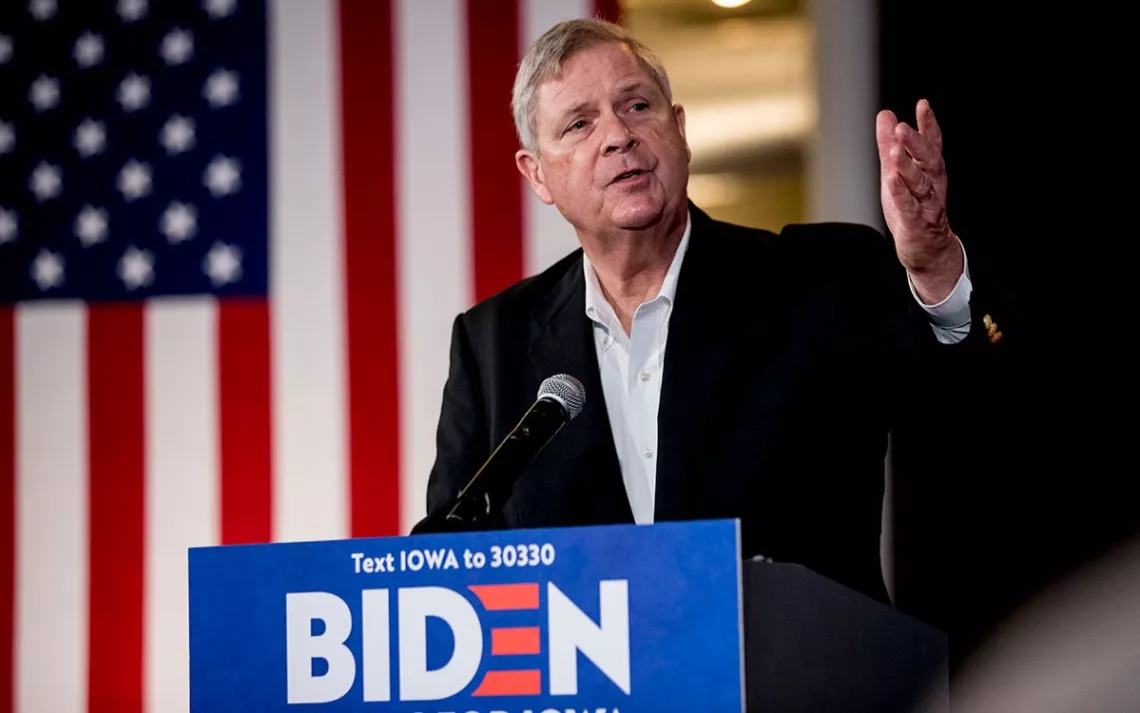

Tom Vilsack for Agriculture Secretary Worries Environmentalists

Vilsack represents a return to a status quo that doesn’t adequately address climate

Photo by Andrew Harnik/AP

Early last week, presidential transition officials announced that Joe Biden would select Tom Vilsack as his secretary of agriculture, a choice that suggests a straightforward—and to some, disappointing—continuation of the Obama years. Vilsack served as governor of Iowa from 1999 until 2007, made a brief run for president, and then became secretary of agriculture for Barack Obama, a job he held for Obama’s two terms until he began work as a lobbying executive for the dairy industry. He’ll be welcomed back to the USDA (which also oversees the US Forest Service) with applause from farm-state Republicans and ag industry lobbyists and with reticence—even outright hostility—from environmental advocates. The announcement was made official last Thursday.

The Department of Agriculture has emerged as a hot-button office during the transition, particularly for the role it could play in mitigating the numerous harms to the environment perpetuated by agriculture, not least of which are the copious greenhouse emissions from livestock and the over-application of manure and chemical fertilizers. A number of progressive activists and environmental leaders are up in arms about the pick, pointing to Vilsack’s friendly history with polluters and failure to enact substantive regulation during his eight years in office from 2009 to 2017. “Pulling Tom Vilsack directly from the dairy lobby to the agency meant to regulate that industry would be disastrous for the climate,” Jennifer Molidor, senior food campaigner for the Center for Biological Diversity, wrote to Sierra. “The US needs a secure, just, and climate-friendly food system, not an agency chief who will continue business-as-usual while the climate crisis grows.”

The opportunity for environmental progress through farming is massive. USDA programs have dramatic influence on the farm system and food supply, which account for an estimated 10 percent of the country’s emissions. The department spends billions of dollars on food for schools and other institutions, contracts that environmentalists would like to see awarded with climate strings attached. Subsidized crop insurance and generous bailouts encourage farmers to strive for maximum production of corn, soy, cotton, wheat, and rice, which accelerate decline in soil and water resources and increase runoff and chemical use. The conventional wisdom on how to solve this problem is straightforward: Conservation programs, popular but underfunded by the Farm Bill, need to be funded on par with insurance subsidies, so that it’s equally or more attractive to retire land as it is to plant crops you don’t even have to harvest to get paid for.

Some progressives are at least reassured that Vilsack’s appointment will offer the opportunity to reverse course on the damage wrought by the agency under Trump’s secretary of agriculture, Sonny Perdue. "We're hopeful that Vilsack, if confirmed, will reverse many of the harmful policies put in place during the Trump administration,” said Alexander Rony, who works on food and agriculture issues for the Sierra Club. “But we also know that a return to the status quo won't be enough to meaningfully tackle climate change and racial justice.” Perdue’s USDA relocated and mortally defunded a vital research office at the department that would need to be revived to develop research-based climate policy; Perdue himself was a vocal skeptic of anthropogenic climate change, even while his USDA unveiled a five-year climate plan, but also actively suppressed climate-focused research. There is certainly no match for Perdue’s cronyism and wanton use of farm bailouts for political gain. While being a better climate ally than Perdue will be easy, picking up the pieces won’t be.

How you feel about the potential for progress on climate in Vilsack’s administration depends on whether you consider multinational agribusiness to be a partner to climate action or its principal obstacle. Vilsack seems to see them as partners, but that hasn’t always led to good results. For one thing, Vilsack has a track record of mounting seemingly sincere challenges to agribusiness—among others, a hopeful investigation into antitrust violations in the livestock industry—that eventually end in capitulation. Shawn Sebastian, People’s Action senior strategist for rural people and planet first campaigns, sees agribusiness as an obstacle to effective action on climate. “Vilsack spent the last four years advancing an unsustainable food system that serves corporate ag monopolies at the expense of family farmers, resulting in an explosion of factory farms that are a primary driver of our climate crisis."

Agribusiness has long relied on the savvy strategy of presenting a set of competing solutions to public problems that open new markets and stave off regulation. In terms of climate, exhibit A is the construction of the Renewable Fuels Standard, which began in 2005 and now diverts 40 percent of American corn to ethanol refineries in the name of energy independence and clean fuel (a solution that hasn’t delivered the promised environmental benefits). Biden’s platform is littered with proposals like this that are hotly contested between industry and activists: offset markets for carbon sequestered in soils, digesters that capture methane from factory farms and process them into “biogas,” and, as the campaign climate plan reads, “doubling down on liquid fuels of the future,” meaning that the much-maligned ethanol program will once more have a passionate ally at the top of USDA.

“It’s too early to know exactly how Vilsack’s overweening boosterism for commodity crop agriculture will deflect and undercut meaningful efforts to confront agriculture’s contribution to global warming,” Ken Cook, president of the Environmental Working Group, told Sierra. “We can’t say with certainty when he might throw his support behind subsidy boondoggles that shower commercial agriculture with taxpayer dollars disguised as “carbon farming,” or oppose efforts to rein in the most egregious forms of farm pollution. But I’d guess sometime around late March.”

Vilsack’s perceived loyalty to the agrochemical industry is also concerning for groups who fight to reduce chemical use. “We urgently need to break away from the corporate-driven agenda of endless consolidation and chemical-intensive production.” Kristin Schafer, executive director of Pesticide Action Network, told Sierra in an email. “Vilsack’s appointment would be a missed opportunity.” Fertilizer overuse has resulted in nitrate runoff that leads to algal blooms and a toxic dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico, contributing emissions of nitrous oxide that make up a significant portion of agricultural greenhouse gases. Factory farms, a source of large amounts of air and water pollution, are regulated under the EPA, but a defensive agriculture secretary could pose a devastating obstacle to strong rules to protect air and water. Vilsack is a Democrat, but his anti-regulation stance is conservative, a position that made him an effective lobbyist for a growth-focused dairy association.

Breaking up highly concentrated agribusiness is another sleeper climate policy long overdue at USDA, but Vilsack harbors a disappointing record on that too. The dissolution of USDA antitrust offices under Obama and Trump has permitted brutal corporate concentration in every livestock sector, which has coincided with an explosion of loosely regulated large animal farms that produce unmanageable amounts of manure. Early in Obama’s first term, Vilsack hit the road with the Department of Justice holding hearings across the country about the monopoly problem, but nothing came out of it, and between 2011 and 2017, factory farms expanded by nearly 8 percent.

Fear of inaction on climate is just one qualm progressives have about Vilsack. His USDA slighted Black leaders and their concerns in a number of ways: A 2019 investigation revealed that the department made misleading and disingenuous claims about its progress on racial justice; the office fell for a Breitbart hoax that painted Georgia’s USDA state director for rural development, a Black woman named Shirley Sherrod, as racist (after seeing a video posted on Breitbart that had been doctored, Vilsack fired Sherrod, then apologized). And, a lawsuit intended to compensate Black farmers for discrimination by USDA was mishandled. Another Black woman, Representative Marcia Fudge, made a public play for the secretary of agriculture position under Biden, received a wave of support, and was funneled to Housing and Urban Development, after saying herself, “it's always ‘we want to put the Black person in labor or HUD.’”

If Vilsack is so flawed, then why has Biden chosen him to lead the agency? It might be because he is listening to those who insist that Democrats’ slipping rural margins need to be shored up with a “safe,” status-quo leader at USDA. Such thinking would be misguided. As Mother Jones’s food blogger Tom Philpott explained in a recent post, “Vilsack [and other white, farm-state corporate centrists] don’t represent rural America, exactly; they represent powerful business interests that operate in rural America, in ways that have not generated broad-based prosperity in a very long time.” George Goehl of People’s Action released a statement that put it more succinctly: “Democrats will continue to lose rural voters with a Vilsack appointment.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club