News from the Chair

Our revitalized Big Bend Group of the Lone Star Chapter is making progress. We recently added Gary Oliver and Francine Richter to the following list of Executive Committee members: Susan Curry, Gail Shugart, Stuart Crane, Lori Glover, and Theron Francis. Susan Curry is updating the membership which should number above 100. Rick Lobello in El Paso is spearheading an effort to get Big Bend National Park designated as an International Park along with several protected areas on the Mexican side of the Rio Grande River. Our group should support that effort and I will prepare a letter to Rick assuming all on the ExCom are in support.

We have spent about $11,000 on an attorney to help us with comments to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) in order to have standing in any possible appeals of their expected decision approving the international crossing of the Trans-Pecos Pipeline to Mexico. Depending on the results of the elections this fall, we may want to revive the effort to have Big Bend National Park congressionally designated as a wilderness area. We thought we were close several years ago when Ciro Rodrigues and Kay Bailey Hutchison supported such action, but they both lost their elections. Currently, most of the park is shown as potential wilderness, but that could be feliminated with a stroke of the President’s pen.

Regards,

Roger Siglin, Chair

Big Bend Regional Sierra Club

Lone Star Sierra Club Director Reggie James to Visit Alpine and SRSU and Alpine April 16-17

By Theron Francis

Reggie James will speak at Sul Ross State University on the Sierra Club’s efforts to protect our environment on the evening of Saturday, April 16. The Sierra Club has worked to limit the expansion of fracking, halt the construction of liquefied natural gas facilities, and - most important to our community - stop pipeline construction. Reggie will give an overview of the Lone Star Sierra Club’s work on the ground in local communities, in the courts, and with the legislature. We will also be able to tell Reggie what we really care about, show him how we have fought for the Big Bend, and suggests ways for the Sierra Club to protect our communities and wilderness areas. Reggie will also meet with members of the Big Bend Regional Sierra Club group to help with organizational planning on Sunday, April 17.

Reggie is an innovative non-profit executive with more than 25 years of experience in consumer and environmental policy and advocacy. As former director of the Southwest Regional Office of Consumers Union in Austin, he has worked on legislative and regulatory advocacy for improved public and environmental health and safety, and for better low-income legal representation. At Consumers Union, he focused much of his efforts on alleviating food safety and public health and environmental problems relating to conventional agricultural and other food production practices. He oversaw advocacy and national online organizing on a range of issue including healthcare, financial services, energy, telecommunications, and other consumer issues. James is also a Navy nuclear submarine veteran.

Reggie is an innovative non-profit executive with more than 25 years of experience in consumer and environmental policy and advocacy. As former director of the Southwest Regional Office of Consumers Union in Austin, he has worked on legislative and regulatory advocacy for improved public and environmental health and safety, and for better low-income legal representation. At Consumers Union, he focused much of his efforts on alleviating food safety and public health and environmental problems relating to conventional agricultural and other food production practices. He oversaw advocacy and national online organizing on a range of issue including healthcare, financial services, energy, telecommunications, and other consumer issues. James is also a Navy nuclear submarine veteran.

Update from Austin

By Cyrus Reed

Though the Texas Legislature is not in session this year, the Sierra Club’s Lone Star Chapter is hard at work engaging committees on interim charges related to energy and environmental policy direction. Interim charges, while not directly tied to legislation, are specific topic areas that the Lieutenant Governor and Speaker of the House request their respective committees to study while the Legislature is not in session. A few of the charges that the Lone Star Chapter is working on include oversight of the Railroad Commission of Texas (including their enforcement policies); continuation of the Texas Emissions Reduction Plan, which helps keep the air over our cities clean; and a review of the various federal environmental rules including those related to haze pollution, ozone pollution, and the Clean Power Plan. Here are links to our recent presentations on both air quality and TERP and enforcement policies at the RRC.

In addition, Conservation Director Cyrus Reed is leading an effort to strengthen the scrutiny placed on the Railroad Commission as it enters its Sunset Review. Sunset Review is a periodic legislative review of each state agency intended to reduce inefficiency and streamline government processes. Thanks in large part to Reed and other’s efforts, the Railroad Commission will undergo Sunset Review next legislative session instead of 2023, as the Legislature had been contemplating. This is an agency in bad need of reform. Not only is there name silly -- they regulate oil and gas and coal mining (kind of), not railroads -- but their enforcement policy is a mess (see above), their Commissioner’s statewide campaigns are funded directly by the oil and gas companies they are supposed to regulate, and they don’t have the needed rules in place to protect groundwater, our air quality from flaring and venting, or our grounds from shaking from seismic activity. Here is a list of the changes Sierra Club has told the Sunset Commission it should make.

We expect the Sunset Commission staff to issue its report in early May, and hold a public hearing in June before the legislature picks up the issues in January 2017. Sierra Club members and supporters (you!) can help put pressure on our state leaders by commenting on the Sunset staff report and/or come out in force to the public hearing to demand reform of this rogue agency! Stay tuned to the Big Bend Sierra Club newsletter for updates!

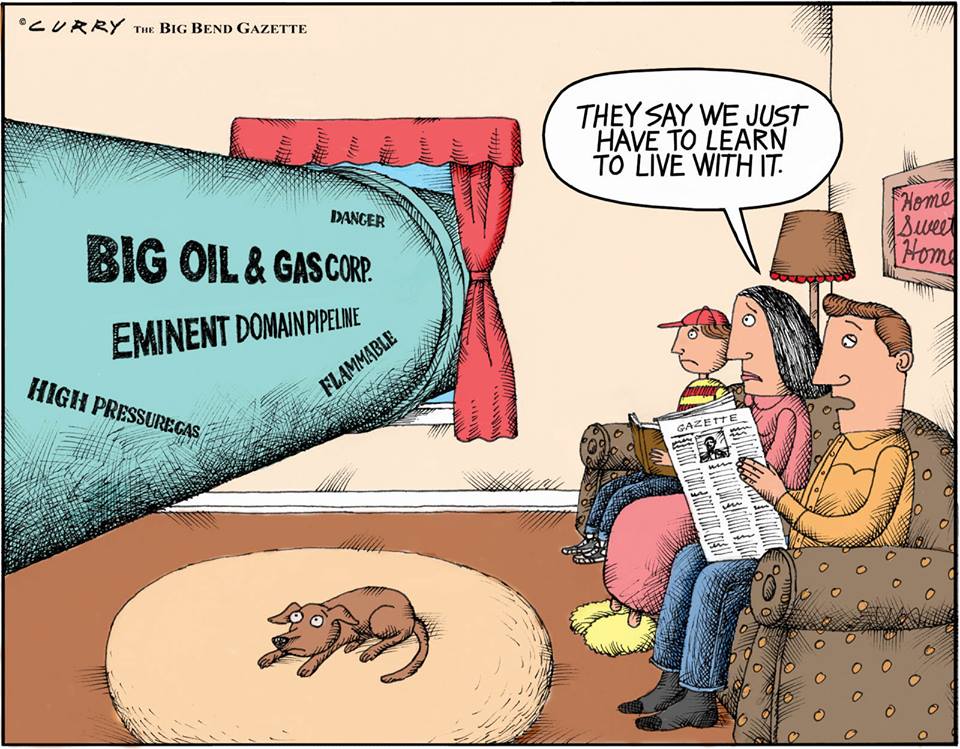

A Cartoon By Tom Curry

Living With Rattlesnakes

By Roger Siglin

I have hiked thousands of miles in rattlesnake country over the last 50 years without being bitten by a rattlesnake. Prior to joined the National Park Service, I spent a summer in the Big Horn Basin of Wyoming doing geology field work and we encountered rattlesnakes almost daily and killed them. Since then, I have not killed one and can think of few reasons for doing so. An exception might be if you are bitten and want a positive identification of the snake. Most of them are very reluctant to strike and if you back away they will not normally follow you. We have two rattlesnake species in our area, the Mojave--which is the most aggressive and has the most toxic poison--and the Rock Rattler.

A rattlesnake bite can have very serious consequences and advice and treatments can be easily found on the internet. We have had several on our front porch in the 10 years we have lived near Alpine and I keep a snake stick handy for picking them up and moving them away. Some of the better sticks have a clamp at the end for grabbing the snake behind the head and a hand grip for closing the clamp. I also have a white plastic 5 gallon paint bucket with a lid and just drop the snake in the bucket, fasten the lid, drive it down the road, and release it far from any residences. We have several other snake species, the prettiest and largest of which is the Gopher or Bullsnake. It will mimic a rattler by coiling and shaking its tail in dry leaves and is often mistaken for one and killed. They can bite but I have often picked them up by grabbing behind the head, as they are normally pretty docile.

Lost Again

By Stuart Crane

The hawk spies the travelers in the weary canyon

Far from any human kindness or comfort.

Kindness is in the eye of the beholder.

Roger beholds the faithful map, peers up the canyon,

Then encourages his companions with pure

Enlightenment; they are Lost Again.

He moves forward through a pile of parched rocks,

Missing a tender claw from one

Of the thorny denizens of Fairbanks South.

Later they might happen onto the

Almighty possibility of a favored place

Lush with ferns and clear restoring water.

But for now Roger shares the great gift,

Well received by his fellow travelers,

That they are Lost Again.

A Metate in the Desert

By Theron Francis

Sierra Club hikers found a metate with a round mano in its center in the canyon folds along the edges of Big Bend National Park not far from a desert spring. The stone was once chosen to be a mortar on which to grind grain because it was nearly flat. Through the process of grinding corn, beans, and seeds over as many as 3,000 years, the metate took on the round, perfected shape of a bowl and it became a better container for the flour ground there. The mano, or grinding stone, also became more round over time. The arm motion of the women grinding the maiz was circular to fit the contours of the metate.

Historian of the Rio Grande, Paul Hogan, writes that women woke before dawn to grind maiz, while the men sat beside them drumming or singing to honor and give rhythm to their work. They pulverized the corn four to five hours a day. We must imagine the men tiring of drumming before the women finished their work. We must imagine the women’s muscular hands, thick arms, well rounded shoulders.

The metate suggests a chain of relations in the environment of the Native settlement. The nearby spring provided water for cooking and washing. The water of the spring could also help with the cultivation of maiz. There was no sign of irrigation, however. Although some of the more urban Puebloan groups used irrigation techniques, the people here were most likely dry land farmers. The more they depended upon rain, the more they had to sing, dance, and pray. The canyon walls above the spring contained caves where corn could be stored away from animals and marauders. Storing corn entailed saving seed corn for the next season, producing food on a renewable basis, and consciously participating in the fertility of life.

Because of its size, the volcanic basalt metate most likely was never moved and remained in situ, a rock of the place. The vugs (holes) in the rock, says geologist Nick Morales, “make the ideal surface to lodge and catch grains for ease in grinding.” Basaltic metates are superior to metates made from other stones, because fewer rock particles break off into the flour.

Maiz is the staff of life for almost all Native Americans. In the Mayan creation story, The Popol Vuh, humans in their present incarnation were created from corn. Corn, the ambrosia of the Americas, made the people godlike. In her book Dwellings, Chickasaw author Linda Hogan writes that “some of their [godlike] vision was taken away, [so that] the mystery of creation and death inspired deep respect and awe for all of creation.” This was not true for the earlier incarnations of people. The mud people, who were built of adobe, melted away in the rain. The people of the next epoch, who were “lovingly” carved from wood, did “not praise the gods. They were hollow and without compassion. They transformed the world to fit their needs. They began to destroy the land, to create their own dead future out of human arrogance and greed. Because of this, the world turned against them.” We, who look upon this metate made by the people of corn, are unfortunately people of wood, destroying the land that sustains us.

Most of what we enjoy now of Mexican cuisine had its origins in a stone like this. Tortillas, enchiladas, tacos, and tamales all could have been made from meal ground at this metate. Atole—a soup made from ground corn or mesquite beans—was made from meal ground here. Pinole was made from meal toasted and ground, often three times. It could be carried long distances while hunting or traveling to other campsites. By adding water and spices it was turned into a delicious drink. Pan de maiz, or cornbread, was given as a gift to travelers or given to men by women who were courting. Corn syrup was made by maidens who chewed the cornmeal until their saliva turned it into sugar.

Rain makes everything grow and flourish. If corn is your staple, however, you must pray for rain. The Tohono O’odham poet Ofelia Zepeda transformed her people’s prayers into a poem titled “O’odham Dances.” The dancers in the poem sing throughout the night “so that rain may come.” They call upon all of existence, all of the animals,

The ones that fly in the sky.

The ones that crawl upon the earth.

The ones that walk.

The ones that swim in the water and

The ones that move in between water, sky, and earth.

They implore them to focus upon moisture.

All life is mutually concerned, sympathetic, and working together in this poem. “All are dependent,” writes Zepeda. The dance goes on until sunrise, when they reach out their hands “to capture the first light.” The renewal of the day is tied to the power of rain to sustain life and make the corn grow.

A Hawksbill turtle surfaced as we approached the reef, the reptile un-spooked by the silence of the sailboat. At the break where the ocean swell meets the coral, a three-foot barracuda flew thirty feet in the air chasing a school of ballyhoo. The week before, at the same spot, an enormous spotted eagle ray also soared out of the water, its rhomboidal body and long tail menacing the atmosphere. My fares that day, two lawyers from the Midwest, each wearing yellow, and I, in orange, donned snorkel gear and jumped in. Below, brain, fan, and staghorn coral greeted us in colors ranging from purple to yellow to red oxide. A school of blue tang cruised past, casting shades of silver and blue against this coral collage. A lone hound fish swam amongst them like a wolf among the sheep. A nurse shark muscled away and a purple moon jellyfish, last of the new extended season, meandered above softly disintegrating. Like many coral reefs, Cayo Blanco is home to hundreds of marine species and is the ocean version of El Yunque, the mountain top tropical rain forest hovering only fifteen miles away that also harbors pockets of extreme biodiversity.

Cayo Blanco is a small island in the Caribbean. My wife Lori and I take tourists out on the 32-foot sloop “WILLO” for snorkeling and sailing. We leave from an anchorage at another island called Vieques, which is off the shore of another island, Puerto Rico. Ninety-five per cent of our trips to Cayo Blanco are hydrocarbon free. Occasionally, the wind quits or the cape effect at Vieques blows wily and we start the gasoline motor. We offer these excursions during the winter season 10-20 times a month, depending on demand which seems to be a function of how cold it gets in Chicago. It has not been a blockbuster year.

I, Captain, meet a lot of people. Different kinds: liberals, conservatives, artists, engineers. Some start the excursion with beer, others with questions. I tell them what I know about the reef, fish, coral, arthropods, sharks, and the environmental challenge all reefs worldwide face today. The general attitude is yes, we know about the acidification of the ocean, and yes, the ocean temperatures are rising and that only 2 percent of marine life exists today compared to 100 years ago, and that we humans are goners if we don’t do something about it. They know these things. They are not happy about it – but they’re on vacation and the ticking clock toward climate catastrophe will have to wait - no bummers, please.

I took a lady out one morning, my only fare that day. She commented on the soft chine of the hull of the WILLO. Nice, I thought, somebody who knows boat design. Turns out she was a photographer specializing in third world architecture juxtaposed with wild animals. She liked Saharan adobes and big cats. Said she shipped tigers to El Aaiun once. A cloud got mean at the reef. Turned black, opened up, barometric pressure dropped. Wind swung counter-clockwise, like a hurricane. The rain poured. We arced at the mooring, stretching the nylon thin, getting too close to the reef. Had to cut the line and motor out. She stood in the cabin photographing my first mate Coral and I navigating in the squall. I felt like a big cat in the third world on a boat with a soft chine. When we got back to the dock safe and sound, she said nonplussed and dry, “I’m twenty short I hope you won’t mind.”

Sometimes I think I’ve got everybody on the same page. Then somebody jumps ship, into the deep blue, underway. A newlywed did this. Her husband had flirted a little too long with the slender German next to him. I’ve got to watch where I seat people. Like the Paris Climate Change Conference of 2015. Sometimes the fare will admit minutes before donning mask, snorkel, and fins, that they don’t know how to swim. Sometimes fares drink all my booze and then ask to lay out on the weather deck while plying scandalous seas.

I find most people are amazed at the reef and are keen to team up and be part of a non-hydrocarbon experience. It’s not always convenient. More work for the crew; winching sheets and dropping sails and if we miss the mooring, hoisting sails and dropping them again. The pure sail trips tend to be longer. I’m working on a no-carbon back-up plan: a solar powered electric motor. So far, with limited deck space for panels, we’re able to generate 80 lbs. of thrust, not nearly enough for our 15,000 lbs. boat. But a company in Finland stitches solar panels into sails and we hope to buy a couple soon.

The wind petered-out coming back from the reef that day. We were an hour late. Once we finally tied up to the mooring, I announced, “Welcome to the hydrocarbon free world.” The fare in the yellow bikini eyed her watch and said, “Looks like a lot of work.”