Part 3 of the Critical Minerals series

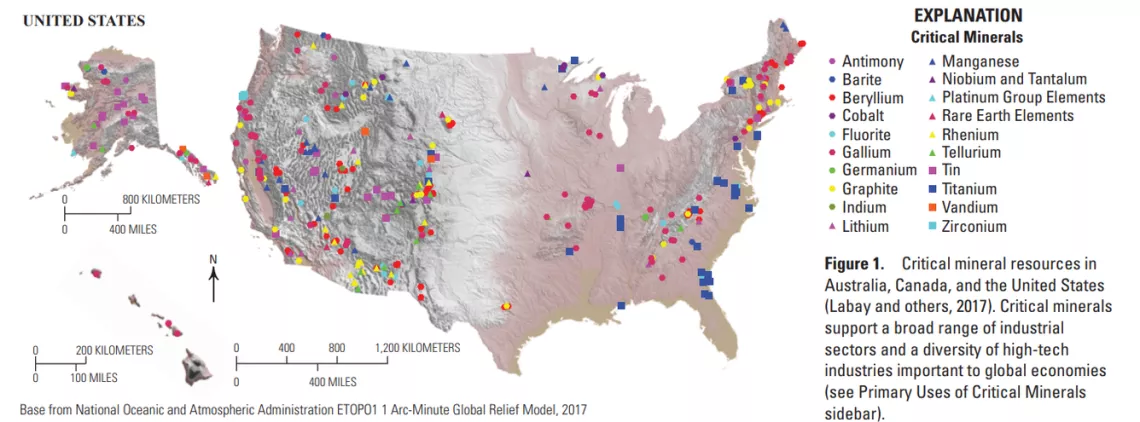

Locations of critical mineral deposits in the United States. US Geological Service, Public Domain.

The purpose of this series is to dig into a few of the minerals labeled critical and explore their properties, uses, and the dangers they present, and to present some alternatives which mining and energy industries don’t tell us about.

In this post, we’ll be exploring what critical minerals are. Or better, what they are defined as.

In the US, critical minerals are a subset of critical materials, which the 2020 Energy Act defines as “any non-fuel mineral, element, substance, or material that the Secretary of Energy determines: (i) has a high risk of supply chain disruption; and (ii) serves an essential function in one or more energy technologies, including technologies that produce, transmit, store, and conserve energy.” The Secretary of the Interior may also define a mineral as critical. Interior’s designations are published in the Federal Register. Here we see cobalt and lithium, along with some less-expected items like aluminum and tin.

Other federal departments, countries, and regions of the world have their own definitions of this term and their own lists of minerals. Here’s a link to info about the EU’s policy, and here is an explainer from the International Energy Agency.

What ties together these definitions is Global North FOMO. Wealthy industrialized countries recognize that China has a leg up in domestic mining and production and has made inroads into Africa. Therefore the race is on to secure the North’s supplies through increased domestic mining and trade relations with mineral-rich nations like Indonesia. These relations are always mediated through gigantic multinational mining corporations like Glencore.

The clash-of-superpowers narrative has many aspects. For example, the US Department of Defense (DOD) maintains a national stockpile of minerals, issues reports, has its own (often classified) mineral requirements and, we can assume, has developed war plans around access to certain resources. By framing the climate crisis as a national security issue, the DOD aggrandizes institutional power, frames the question of climate solutions as one of supply rather than demand, and allies us with known bad actors in the mining world. And politically, a national defense argument is almost unanswerable.

Another important aspect of the critical minerals narrative is domestic mining. If we must get materials from reliable sources, the standard argument runs, then domestic mining must be sped up through faster and looser permitting.

This is a huge and complicated topic, and this post hasn’t even discussed issues like steel, concrete, or land use. We’ll leave you with four questions if you are thinking, acting, or advocating around mining:

- Who is defining a mineral as critical?

- What are their standards?

- Who benefits?

- Who suffers?

The full Critical Minerals series can be found at the links below: