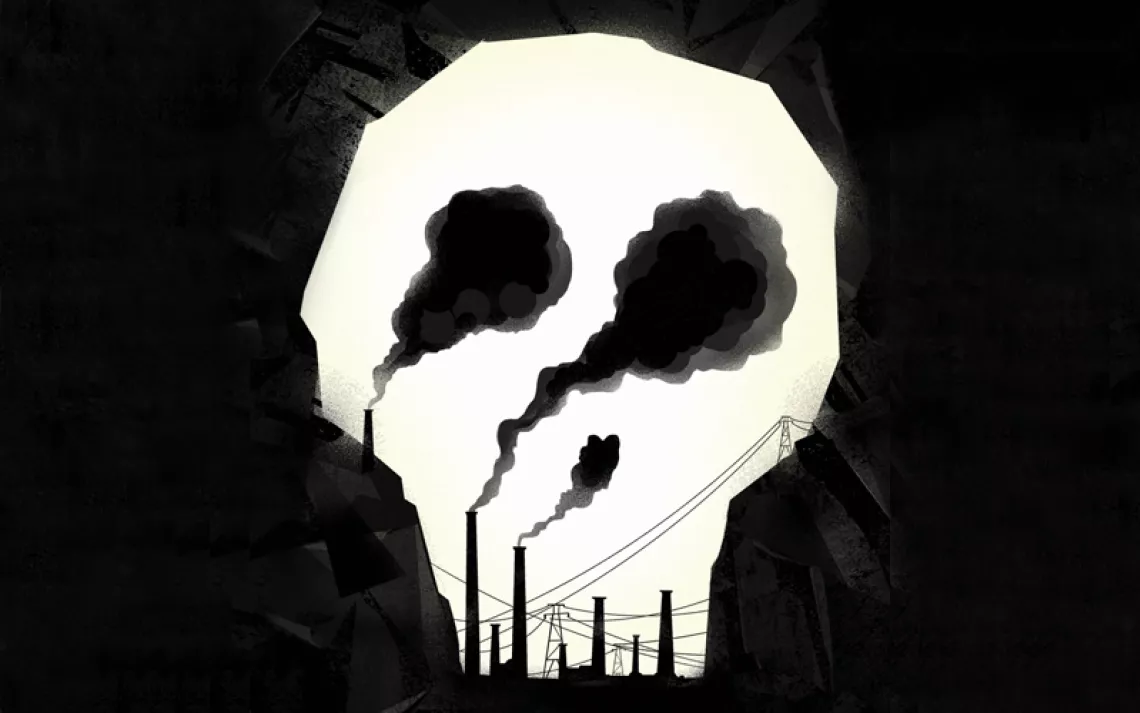

The Cost of Coal, Combustion: Michigan

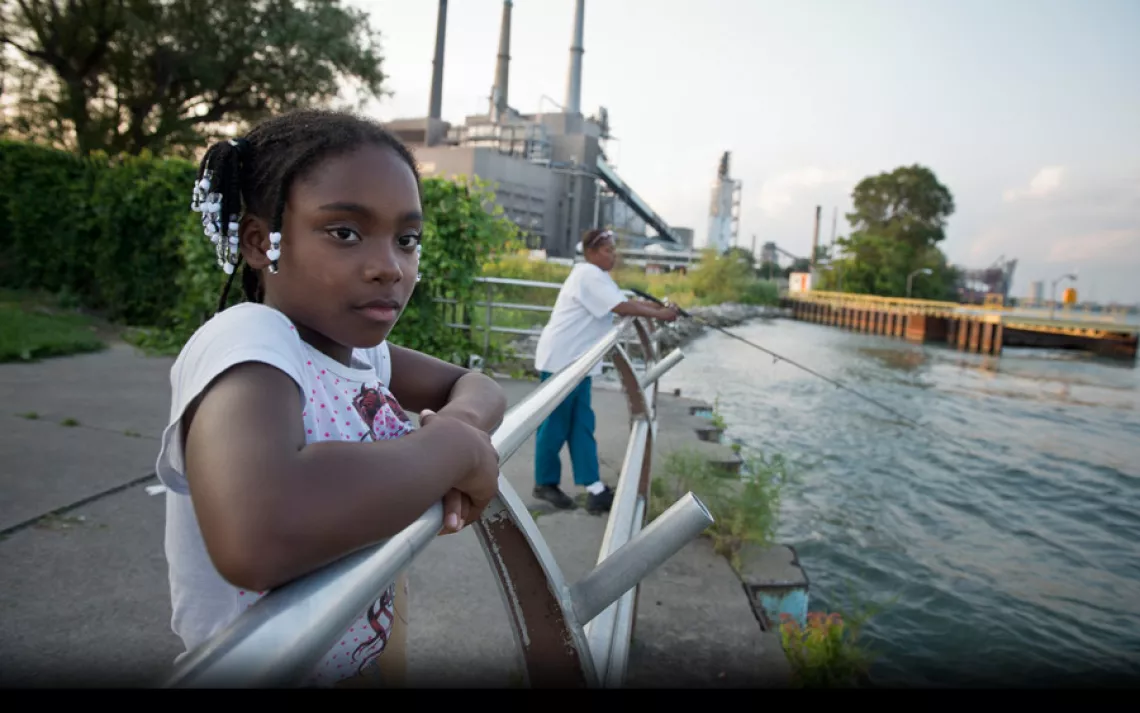

River Rouge, Michigan, is in sniffing distance of a coal-fired power plant, an oil refinery, a sewage-treatment plant, a steel mill, and other industrial polluters.

For generations, people in River Rouge, Michigan, have lived within sniffing distance of a coal-fired power plant, an oil refinery, a sewage-treatment plant, a steel mill, and other industrial polluters.

No studies have precisely measured the cumulative health impacts of those operations on nearby residents, but in 2009 the nonprofit Clean Air Task Force calculated that particulate pollution from coal combustion at the River Rouge Power Plant alone (one of nearly 400 coal-fired plants still in operation nationwide) is annually responsible for 44 deaths, 72 heart attacks, and 700 asthma attacks in the surrounding community.

Photos by Ami Vitale/Panos Pictures

Siobhan Washington

River Rouge, Michigan

Marianna Hildreth, 7, holds her cousin Mariyah McGhee, 1, who has asthma, in their grandmother's kitchen in River Rouge, Michigan.

My father was an outdoorsman. The whole family was constantly taking camping trips. My father bought property over in Canada. The very first time I went over there, I was like, "Oh. My. God. You can breathe!" When we came home to River Rouge, you could see the haze over the city--this orange and green haze. I begged to go back.

Outside her house in River Rouge, Michigan, Siobhan Washington holds grandson Anthony Johnson, who has asthma.

Me and my girlfriends talk about this all the time. About the pollution and how it's time to get away and go somewhere where you can breathe and you're not living next to all this.

Siobhan Washington plays with her grandchildren in her bedroom.

I don't understand why more people aren't concerned about it. People are dying off, slowly but surely, in their 20s, 30s, 40s, and 50s. When my great-grandmother passed away, she was 106 years old. And when my mom's mom passed away, she was 76. My mother was 66. They're dying younger.

Siobhan Washington's granddaughter Mariyah McGhee, who has asthma, holds the leg of her mother, Jasmine McGhee.

My grandbabies have asthma. My daughter has an inhaler with her wherever she goes, for her and her daughter. When I went to visit them yesterday, there's my granddaughter with a mask on her face. I didn't have that growing up. Nobody had asthma in my family.

Anthony Johnson sleeps on lap of his mother, Ashley Rivers, as his sister, Ava Rivers, walks away. Both children have asthma.

Watching my kids not being able to breathe is hard. It hurts as a grandparent.(Interviewed August 13, 2012)

Kevin Morris

Detroit, Michigan

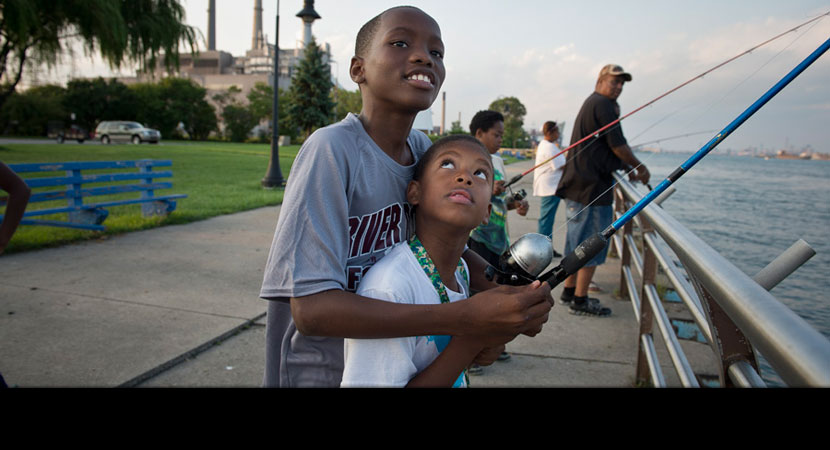

Just across the water from the intensely industrialized Zug Island, Kevin Morris shows off the bass he caught in a Detroit River canal. "Driving here, it's like entering another world," said Morris, who lives in Detroit. "It's almost what a Third World country would look like.

There are signs posted all up and down the Detroit River that tell you what type of fish have the most contaminants. It's a scale from good to bad, with the fish that are good at the top. Those are the ones I eat, the ones on the top.

Kevin Morris of Detroit fishes with his mother-in-law, Mary Lee. He eats only predatory fish, which are migratory. Health advocates routinely pass out flyers along the river warning that certain kinds of fish shouldn't be eaten because they might be contaminated.

I only eat predatory fish: walleye, perch, silver bass, muskies, northern pike, like that. They don't sit in one spot like, say, a catfish. That's a bottom-feeder, so whatever's on the bottom, they're going to contain it. Around here it's mercury.

Just across the waterway from Morris's fishing spot is Zug Island, home to a steel mill and piles of coal.

See those piles over there across the water? That's coal. Stand here during a northwesterly wind and you can feel it. You get it in your nose, your ears, on your clothes. I wouldn't recommend anyone fishing out here when the wind's blowin' from that direction.

Seems to me there should be some type of screen over it. But I'm only a guy that's fishin', versus a billion-dollar corporation. (Interviewed August 15, 2012)

Alisha Winters

River Rouge, Michigan

Alisha Winters and her seven children.

I've been in Ecorse and River Rouge for the past three years, almost four. I have seven children. We live in Rouge now, right by the train station that brings in coal to the power plant and the steel plant. We're right in the midst of it.

I was shocked when people started telling me that we're in one of the most polluted areas in Michigan. Sometimes when you drive out here, you have to roll up your windows. You're like, "What is that smell?"

Alisha Winters's son Jayvon Riley, 11, fishes in the Detroit River with his friend James Beverly, 7. Health advocates routinely pass out flyers along the river warning that certain kinds of fish shouldn't be eaten because they might be contaminated.

Two of my children have asthma. My son has had asthma since he was born, and my daughter was just diagnosed this summer. It very much took me by surprise. She had to be rushed to the hospital. She stopped breathing. Now she has an inhaler that she has to use daily.

Nikeya Aaron, 9, enjoys a moment of weightlessness in Belanger Park, which is sandwiched between the coal-fired River Rouge Power Plant and a massive steel mill.

If you circle around in this community, you'll see a lot of people on oxygen, a lot of people with cancer. They don't really have a clue what happened or where it started.

From right: Alisha Winters invites Kamajia and Kerriona Corbin to a Sierra Club–sponsored community meeting featuring University of Michigan professors who published a study showing how air pollution affects children's health and academic scores throughout the state.

I volunteer. That's my passion. I enjoy being able to help and serve the people of River Rouge. I feel like my obligation to the community is to make them more aware. Most of the people here have been at the bottom of the bottom. But if I can smile through my ordeal and pass my smile off to someone else, my day is worth waking up. It's worth getting dressed and doing things like going out in the rain to help with the farmers' market. It's also a good role model for my kids. All of my children are involved in volunteering.

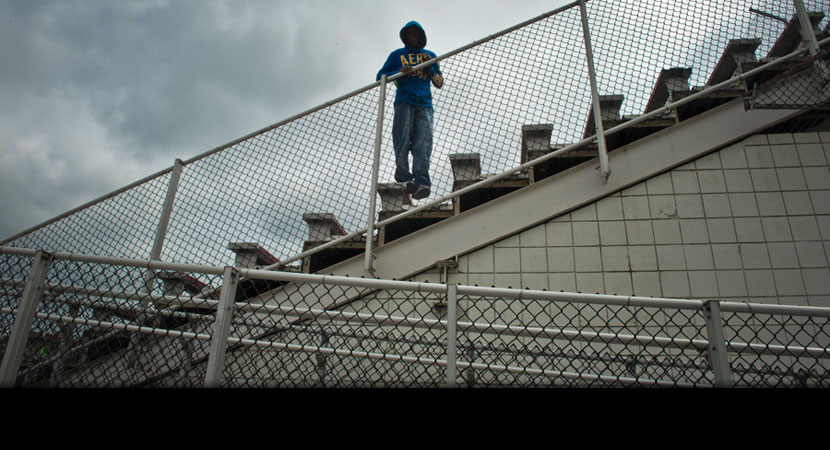

Robert Connor looks down from the football stadium bleachers at River Rouge High School.

I'm very hopeful. I'm excited. Because I know that I play a role in it. In 10 years I picture Rouge being a very clean, safe environment for our children to live and work. Together, we're going to do great things to make it better for our children. I say that with great confidence. It's gonna happen. (Interviewed August 13 and 15, 2012)

Robert Washington

River Rouge, Michigan

I grew up around here. I love it here. With Rouge being so small, you're one person away from knowing everybody.

We never were told that we could have potential breathing problems. We weren't really too concerned with it as kids. Everybody had a family member who worked at one of the plants around here, and it was like, if you want them to stop polluting, that means they'll have to shut down the place, and that's jobs!

Then people started noticing this stuff that would land on your car and get on your house. I remember in the '70s, my dad's car would always have a light orange dust on it. We'd go to sleep at night and wake up in the morning, and there'd be like a fine, orange-colored dust on it. He'd just rinse it off. Didn't complain to anybody. It was just like a part of your day.

That's how everybody treated it. They figured they'd just deal with it. But then we started finding out that this stuff can cause long-term effects. It can mess up your breathing.

I'm glad people are finally starting to pay attention to it. (Interviewed August 12, 2012)

THE COST OF COAL

Videos | Photo Gallery | West Virginia | Michigan | Nevada

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club