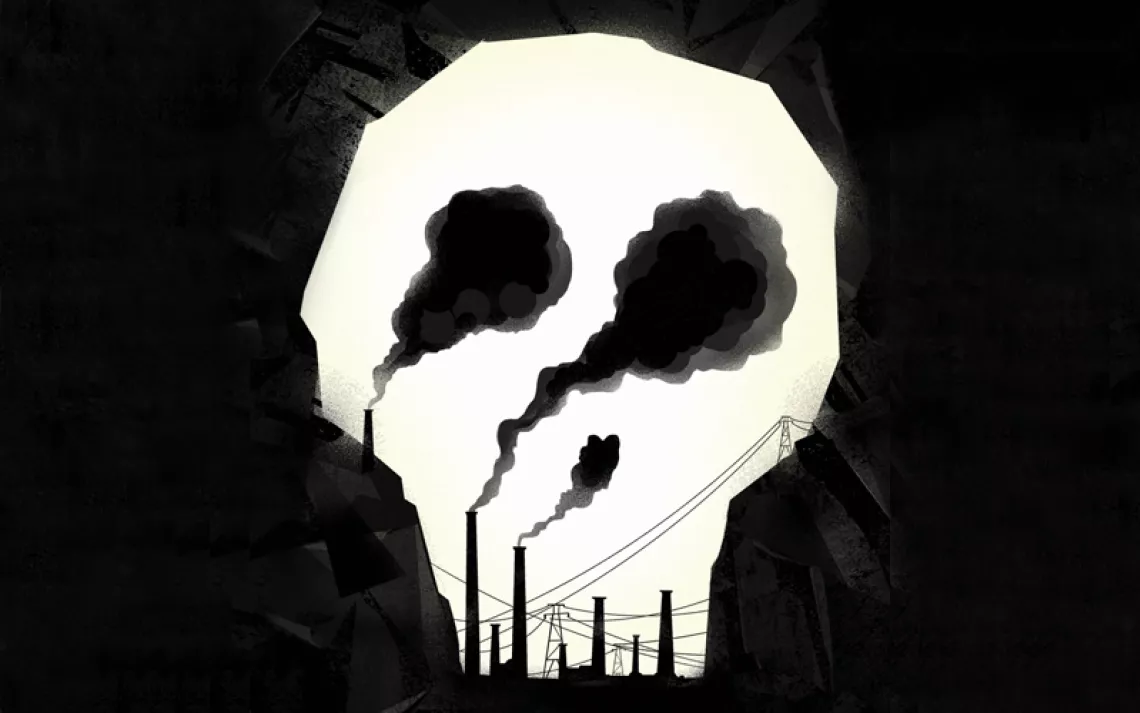

Warren Buffett's Coal Problem

To run his coal trains, the billionaire investor needs to seize land from a bunch of Montana cowboys.

IT'S EASY TO SEE WHY WARREN BUFFETT is called America's most admired investor. The 82-year-old chairman and CEO of Berkshire Hathaway has made gobs of money—$53.5 billion, at last count—and has pledged to give away 99 percent of it. Despite his wealth, Buffett is folksy, unpretentious, and grateful for what he describes as his good luck. He lives in the modest Omaha, Nebraska, home that he bought in 1958 for $31,500 and eats at the local Dairy Queen. (He owns the chain.)

Buffett also gets favorable attention—and deservedly so—for Berkshire's large investments in solar power, wind farms, and the Chinese electric car company BYD. When Berkshire's Iowa-based MidAmerican Energy Holdings Company bought a 579-megawatt solar photovoltaic project in California's Antelope Valley in January, the headlines read, "Warren Buffett in $2 Billion Solar Deal" and "Warren Buffett Continues His Solar Buying Spree." So influential is Buffett as an investor that solar stocks surged on the news. MidAmerican's renewable energy unit also owns a 550-megawatt solar project in San Luis Obispo County, California, and a 49 percent stake in a 290-megawatt solar plant in Yuma County, Arizona. Those are among the biggest solar projects in the world.

A subsidiary of MidAmerican, called MidAmerican Energy Company, a regulated utility with customers in Iowa, Illinois, South Dakota, and Nebraska, has helped build Iowa's thriving wind power industry. Thirty percent of its portfolio is wind-powered generation. "It has been a great and low-key leader," says Bruce Nilles, senior director of the Sierra Club's Beyond Coal campaign.

But Buffett has a problem—a coal problem. In addition to its solar and wind operations, MidAmerican Energy Holdings relies on coal for roughly half of its 18,000-megawatt generating capacity. Buffett's Burlington Northern Sante Fe (BNSF) Railway Company derives a quarter of its $20 billion in annual revenues from transporting coal, and it lobbies aggressively on the industry's behalf. Berkshire Hathaway is one of the very few major U.S. companies that don't disclose their greenhouse gas emissions, and it has opposed shareholders who ask it to do so.

Nowhere is Buffett's green reputation taking more of a beating, though, than in a remote and sparsely populated corner of southeastern Montana. Ranchers, Native Americans, and Amish farmers there are fighting to preserve their livelihoods and landscapes, which are threatened by what, if developed, would be one of the biggest coal strip mines in the West. And shipping all that coal to West Coast ports would be Warren Buffett's BNSF Railway.

This is not postcard Montana, the Big Sky Country around Yellowstone National Park where celebrities pay millions for ranches that they enjoy for a few weeks every year. Southeastern Montana is rugged and beautiful, but also arid and inhospitable, dotted with the remains of log cabins built by 19th-century homesteaders and abandoned long ago. East of Billings, the closest thing you'll find to a celebrity is a 77-year-old cowboy poet named Wally McRae, who has been honored for his poetry by the National Endowment for the Arts and whose books include the aptly named Cowboy Curmudgeon. (See "Cowboys and Coal Ash Don't Mix," March/April 2010.)

The McRaes have been ranching in the area since the 1880s, before Montana was a state. It's impolite to ask how much land Montana ranchers own or how many cattle they run—it'd be like asking New Yorkers how much money they have in the bank. I'd guess that McRae and his 50-year-old son, Clint, run about 500 cows on 30,000 acres of desolate prairie. They move their herd from pasture to pasture on the Rocker Six ranch together on horseback. "An old man and an incompetent," says Wally, drawing a good-natured laugh from Clint.

Just a few miles away is the small town (population 2,300) of Colstrip, which is, yep, named after a coal strip mine. The open-pit mine feeds a 2,094-megawatt power plant, the second-largest coal-burning plant west of the Mississippi and the dirtiest coal plant in the West.

The strip mine has drained water from the aquifers that make ranching possible, but it's the power plant that really gets Wally going. (In March, the Sierra Club and the Montana Environmental Information Center sued the plant, seeking tougher air pollution controls.) Montana's environmental regulators acknowledge that its toxic coal-ash ponds have been leaking for years. "The state could be fining them $10,000 a day for the last 30 years, and you know how much they've been fined?" Wally asks. "Zero." At a community meeting, he once told a power plant executive, "Your industry has turned me into a complete asshole."

And that was before someone—someone who doesn't know Wally, apparently—drew up the latest route for the Tongue River Railroad. Arch Coal, one of America's largest coal companies, wants to stripmine the Otter Creek coal tracts in Powder River County, and the proposed 42-mile Tongue River rail line would link the mine with BNSF. (Buffett's BNSF is a one-third owner of the Tongue River line.) Nine of those miles slice through the McRaes' Rocker Six ranch. "It cuts the ranch right in half," laments Clint. Should the railroad win federal and state approval, Tongue River might be able to use the power of eminent domain to acquire the portion it needs. "Why should we have to give up our property rights for this railroad?" Clint asks.

WALLY, CLINT, AND MANY OF THEIR NEIGHBORS—including a small settlement of Amish farmers who don't even use electricity, as well as numerous members of the Northern Cheyenne tribe, whose ancestors have lived here for centuries—have joined together to fight the coal mine, the railroad, and plans to expand the ports in Washington and Oregon that are needed to ship the coal to Asia. Backing the cowboys and Indians are the Sierra Club, the National Wildlife Federation, and the Northern Plains Resource Council, a local conservation group. They're up against Arch Coal, BNSF, and two of America's richest men: Buffett and Forrest E. Mars Jr., the reclusive candy billionaire who owns a 100,000-plus-acre ranch in Birney, Montana, not far from Colstrip. Mars, 81, fought Otter Creek and the Tongue River Railroad until, in an unexpected twist, he bought a share of the rail line—and its track was routed around his property.

The proposed Tongue River rail line would cut right through the middle of Clint (left) and Wally McRae's Rocker Six ranch. "Why should we have to give up our property rights for this railroad?" Clint asks. | Photo by Tony Demin

The stakes are high. Otter Creek contains about 1.2 billion tons of coal. If the Tongue River Railroad is built and ports are expanded, other mines could follow. "There are a few crucial choke points on this planet where we have some chance of stanching the endless flow of carbon into the atmosphere," Bill McKibben, the activist and founder of 350.org, tells me. "On that list, none may be more important than Montana."

What does Warren Buffett think about energy and climate? Finding out is no easy task. Unlike his good friend Bill Gates (who sits on Berkshire's board of directors), Buffett has said almost nothing about either topic, and Berkshire has no environmental policy, as best as anyone can tell. (Buffett declined to be interviewed for this article.) In addition to its substantial holdings in wind and solar power, Berkshire's investments include a 1.98 percent stake in ConocoPhillips, one of America's largest oil companies, and a 4.37 percent stake in Phillips 66. MidAmerican Energy Company, the same Iowa-based utility that runs all that wind power, also produces nearly half of its electricity from burning coal. It will burn less in the future, however, after reaching a settlement with the Sierra Club under which it will phase out coal burning at five units, clean up another two, and build a solar installation at the Iowa State Fairgrounds.

Another subsidiary of MidAmerican Energy Holdings is the utility PacifiCorp, which operates in six western states. It has an even dirtier mix, with 58 percent of its electricity from burning coal. (The national average is about 40 percent.) "PacifiCorp is stuck in the dark ages," the Sierra Club's Nilles says.

Cathy Woollums, a senior vice president at MidAmerican Energy Holdings who guides the company's environmental work, notes that PacifiCorp has added a gigawatt of wind generation—representing nearly 10 percent of its generating capacity—since it was acquired by MidAmerican in 2006. It is also accelerating the shutdown of its coal plant in Helper, Utah, by five years, to 2015.

By phone, Woollums tells me that MidAmerican's utilities would like to substitute cleaner sources of energy for coal where it is cost-effective to do so. But, she says, the company also has to keep electricity affordable to satisfy customers and regulators. "We don't set policy," Woollums says. "Without a clear [federal] climate policy, it's difficult for us to move forward quickly."

But Berkshire's BNSF Railway, which wants to expand its coal business, has used its influence to oppose government efforts to regulate the industry. As the largest hauler of coal in the country, BNSF is a member of the American Coalition for Clean Coal Electricity, which fights EPA efforts to regulate coal pollution. It's also a founding member of the Alliance for Northwest Jobs and Exports, which is campaigning for four proposed coal-export terminals in Washington State and Oregon—crucial for the industry as domestic demand for coal continues to decline. Nilles calls BNSF "one of the very worst actors when it comes to lobbying and promoting expanded coal use."

Backers of the export terminals say that they will create needed jobs and tax revenues. Reached by email, a BNSF spokesperson says that "railroads are the most environmentally friendly mode of transportation"—which is true, but doesn't account for what's being transported. Matt Rose, the railway's chairman and CEO, told Washington State's Columbian newspaper last August that developing nations in Asia want low-cost energy, just as the United States did when it was industrializing. As to whether supplying Asia with coal would accelerate global warming, Rose said, "I don't address climate change, because I'm not qualified to."

Buffett hasn't really addressed climate change, either. In response to a question at Berkshire's annual meeting in 2007, he did say, "I think the odds are good that global warming is serious." But four years later, at his urging, Berkshire Hathaway shareholders rejected a proposal that would have required the company's utilities to set goals for reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Last year, hoping to get Buffett's attention, Canadian climate activists threatened to block a BNSF train carrying coal to Vancouver. The railroad obtained an injunction against the blockade, and 13 protesters were arrested. Buffett remained silent.

THERE'S NOT MUCH TALK ABOUT CLIMATE CHANGE IN MONTANA, either--not even from those who oppose the proposed Otter Creek mine and Tongue River Railroad. The ranchers are mostly worried about how coal affects their water and the safety and health of their cattle. They especially dislike the idea that a railroad company can use eminent domain to take their property in pursuit of private gain.

"This steamrolling over people's property rights is a dangerous thing," says Nick Golder, 78, a lifelong rancher and political conservative. "Where's the public necessity to ship coal to China? Do we want to help them build up their military industrial complex on the backs of slave people?"

Clint McRae and a number of his neighbors felt so strongly about the issue that they traveled to Seattle to speak at a public hearing on the proposed coal-export terminal north of Bellingham. "The coal will go to China, the profits will go to the coal and railroad companies, and Montana will be left to pay the costs," testified Mark Fix, another Montana rancher.

Nor did climate change come up at a January hearing in the town of Lame Deer, on the Northern Cheyenne reservation. The tribal members who lined up to tell officials from the Montana Department of Environmental Quality what they thought of the Otter Creek mine had even broader concerns.

"I've got spiritual ties to this land," says Otto Braided Hair Jr., who works on the reservation. "Emotional ties. Historical ties. We're just stewards of this land." (Braided Hair is a descendant of survivors of the notorious 1864 Sand Creek massacre, in which Colorado militia attacked a village of friendly Cheyenne and Arapaho.) "Is this whole place going to be turned into a black pit, and then it's gone? Are you going to have grandchildren? Are you going to have great-grandchildren? What kind of land are you going to leave them?"

Alaina Buffalo Spirit is an artist who grew up alongside the Tongue River. She spoke about how she'd recently walked along its banks, enjoying the peace. "They will rape the land, the water, the air, and then they will leave in 20 years," she said, her voice trembling. "Why ruin our land, air, water, culture, our people?"

Such appeals are unlikely to sway Montana's industry-friendly Department of Environmental Quality, which has never turned down an application for a mining permit. Opponents probably have a better shot at stopping the Tongue River Railroad, without which the mine won't be developed. That's because the Surface Transportation Board, the federal agency that will decide the railroad's future, is required to assess its environmental impact under the National Environmental Policy Act. Lawyers for the Tongue River Railroad will try to limit environmental review to immediate impacts on air and water, but opponents will insist that the railway's potential to unlock 20 million tons of coal a year needs to be taken into account.

"I believe that the law is very clear," says Missoula environmental lawyer Jack Tuholske, who represents the Northern Plains Resource Council and the McRaes' Rocker Six ranch. "The board needs to look at all the impact--beginning at Otter Creek, up the Tongue River, to the Burlington Northern main line, and the impact on all the communities along that line, and the export communities. They're all interrelated."

The coal industry, hell-bent on expanding its exports, will ignore global warming. But a federal agency charged with weighing the environmental consequences of a coal-carrying railroad should do better. So should America's most admired investor.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club