Warrior Up!

To ship coal from the Powder River Basin to China, you have to go through the heart of the Lummi Nation.

The bay is a dull pewter sheet, water and sky beautifully indistinguishable. Cormorants, gulls, and scoters glide and dip, slurping ooligan, crustaceans, and the occasional herring. Harbor seals surface and stare. Ospreys eye the shallows for flopping pink salmon. An autumn sun warms the saltchuck--the cobbled intertidal zone--and the shoreline forests of alder, fir, and madrone.

The coho are running, chasing the scent of their natal creeks. Below them, waves of eelgrass undulate, reflecting and breaking the sunlight into a shadowy marine veld. A few bits of herring roe manage to cling to the gentle strands, the last hopes of a once-great fishery.

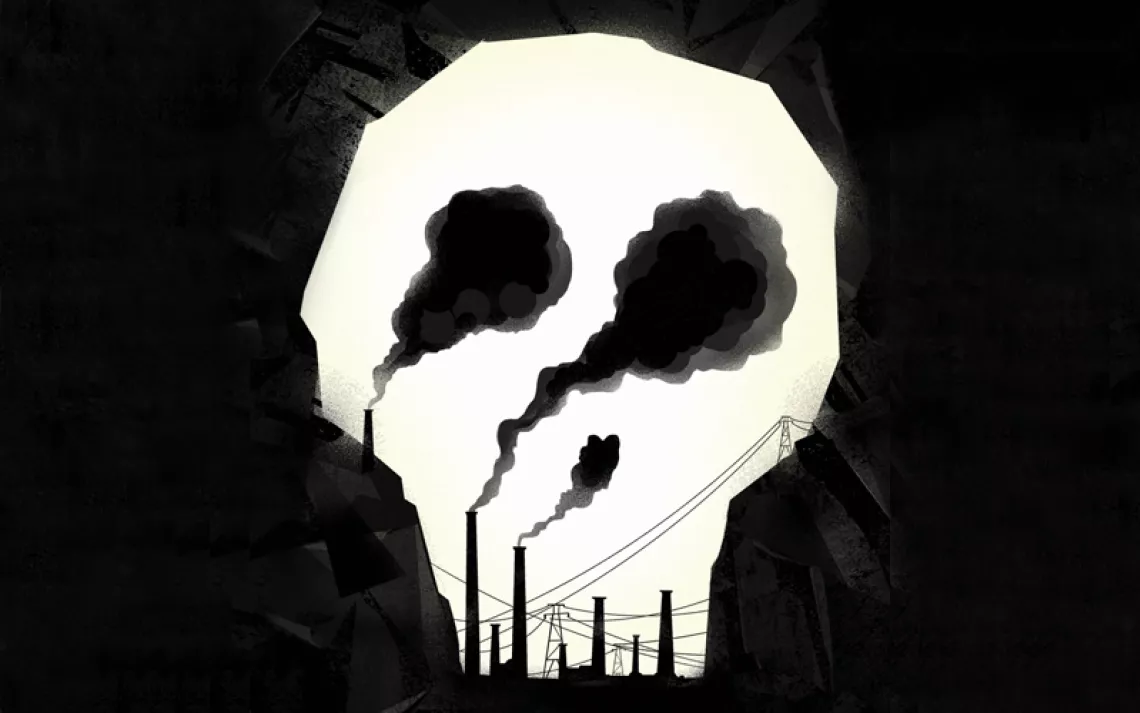

As the mist begins to lift and the dividing line between water and atmosphere becomes visible, a hulking, 300-foot tanker looms at Cherry Point, already the site of extensive industrial facilities and shipping terminals. A proposed new deepwater port here to export U.S. coal to China would doom any hope for reviving the Lummi Nation's traditional fishery.

In this far northwestern corner between Bellingham, the North Cascades, and Vancouver, British Columbia, fishing for salmon and herring supports a rich local culture, as it has for millennia. For the Lummi Nation, a community that has existed at Cherry Point for 175 generations, the annual migrations of sockeye, coho, chinook, pink, and chum salmon to the Nooksack River are their literal and spiritual connection to the earth. It would be hard to overstate their importance to a society that has developed what is still the most sustainable fishery on the West Coast.

"They would work three months and celebrate for nine," Jewell James, a prominent Lummi Nation member and master totem carver, says of his ancestors at the 3,500-year-old fishery. "Every fisherman was required to provide not just for his family, but to keep fishing until there was enough for all. No one ever went hungry."

If a visitor could travel back 500 years, a good deal of the scene at Cherry Point (Xwe'chieXen in the Lummi language) would be recognizable. The ospreys, harbor seals, and gulls would be feasting. The eelgrass would filter the sunlight, and the salmon would be returning. But there would also be some major omissions.

"Well, there'd be no Arco or Intalco," James says, noting the massive aluminum smelter and oil refinery now situated on his ancestors' traditional grounds. "The forest would be different--big cedar and firs all the way down to the water." Today, scrubby primary alder forests dotted with cottonwood and small firs creep to the shoreline. "The waterfowl would be so thick at times, the sky would be black. And there would be people fishing." Xwe'chieXen, he says, was a primary site for ceremonies celebrating the "first salmon," a staple of traditional culture throughout the Salish Sea region.

Today, massive ships arriving at existing industrial facilities at Cherry Point continually drag thousands of dollars of Lummi crabbing gear to destruction. Shipping lanes reduce and clog the fishing ground. Just to the north, at the mouth of British Columbia's Fraser River, dust from coal shipments turns net floats as gray as a December afternoon.

In 2011, SSA Marine began filing permit requests to build a new coal export terminal. In addition to the snaking trains carrying crude oil to refineries and the endless conveyor of tankers toting the refined fuel to China and India, the proposed terminal would be capable of shipping 48 million tons of coal per year. Up to 18 additional trains per day--open hoppers loaded with coal stripmined from Wyoming's Powder River basin--would run through the heart of the Lummi Nation. The coal would then be transferred onto vessels three times the length of a football field, shipped over sea lanes that would eat upwards of 20 percent of Lummi fishing grounds, and finally delivered to power plants in Asia, primarily in China.

While the communities of Bellingham, Ferndale, and Blaine debate the trade-offs between an increase in dockside jobs and the cost of a series of multimillion-dollar rail overpasses (of which Burlington Northern would be obligated to pay no more than 5 percent), the Lummi Business Council has dug in. In the past, tribal opposition to large-scale resource-extraction projects has sometimes been assuaged with fishery offsets or other mitigations. This time, Lummi elders, youngsters, and fishers gathered in September 2012 to protest at Cherry Point with traditional drumming and singing, sending a public message that their fishing grounds were not for sale.

Tribal members underscored that message by ceremonially burning a giant check on the beach at Cherry Point. "The Lummi Nation cannot see how the proposed projects could be developed in a manner that does not amount to a significant impairment on the treaty fishing right and have a negative effect on the Lummi way of life," Lummi Business Council chair Tim Bellew wrote to the Army Corps of Engineers. "These projects would without question result in significant and unavoidable impacts and damage to our treaty rights."

What makes Lummi Nation opposition so serious is a 1974 landmark ruling by Western Washington Federal District Court Judge George H. Boldt: that the 1855 treaty granting the Lummi the right to fish in their "usual and accustomed places" with a take "in common with" non-Indian commercial and recreational fishers actually means what it says. Boldt determined that "in common with" means up to half the harvestable catch. He also held that the treaty gives the tribe a right to co-manage the fishery with state and federal governments--a critical victory. His decision was upheld on appeal to the Ninth Circuit and later largely affirmed by the U.S. Supreme Court. Overnight, tribal fishers--who had previously skirted the edges of their traditional fishing grounds, competing with a far larger non-native fleet--owned half the salmon in Puget Sound and played a role in managing the fishery.

Today, the Lummi Nation isn't interested in giving up any percentage of its salmon runs. Unlike the hordes of college students, kayakers, and recreational fishers wielding NO COAL TRAIN signs at public hearings, it has 40 years of legal precedent and a sovereign contract with the U.S. government backing its claims.

And those claims extend beyond salmon. Boldt's ruling has since been expanded to include several species of fish and shellfish. For Cherry Point and the surrounding areas, this includes butter clams, geoducks, and--crucially to the coal issue--herring. With its deepwater access, eelgrass for sheltering roe, and rich nutrients, Cherry Point was once one of the best herring fisheries on the West Coast. For thousands of years, Lummi villages would net, rake, and feast on the oily fish. By 1979, though, herring stocks had gone into free fall, and the Lummi Nation voluntarily elected to forgo its right to fish for herring in an effort to bring the population back, at an estimated loss to the tribe of more than $100 million since that time. In 2000, the Washington State Department of Natural Resources designated most of the waters around Cherry Point as a marine reserve, in part as a means to preserve herring habitat.

The second phase of the Boldt decision upholds the tribe's contention that its treaty guarantees it the right to abundant salmon populations. That means that the state has an obligation to protect salmon habitat. In 2007, the federal district court in Seattle ruled that the majority of road culverts designed and maintained by the state are insufficient to allow returning salmon to spawn, in violation of the 1855 treaty. Since then, Washington has spent tens of millions of dollars upgrading antiquated culverts, while at the same time appealing the decision. In January 2013, Judge Ricardo Martinez issued a permanent injunction, directing the state to continue the mitigation work in a timely manner. The case is now headed to the Ninth Circuit, but if Washington has to replace hundreds of old storm culverts in deference to the Martinez decision, it's hard to see how SSA Marine's huge proposed shipping terminal could operate in a way that doesn't violate tribal treaty rights.

Between the shade the massive ships will throw upon the eelgrass beds (depriving them of chlorophyll), the shoreline erosion from increased traffic, and the known and predictable hazards of fuel spills and coal dust, the Lummi Nation considers a behemoth coal terminal in the middle of this fragile and recovering fishery both a madness and a sacrilege. Jeremiah "Jay" Julius is a commercial fisher whose great-great-great-great-grandfather was one of the signatories of the 1855 treaty. "The tankers are the trains that killed off the buffalo," he said at a tribal habitat forum. "These tankers are going to kill my way of life. So, to me it is a battle."

The coal terminal would threaten the Lummi way of life in other respects as well. Cooling the coal awaiting shipment at Cherry Point would require vast amounts of freshwater: 5.3 million gallons per day on average but up to 55 million in the summer. That amounts to 140 percent of the Nooksack River flow. "How does that affect our ability to fish the Nooksack?" Julius bristled at the forum. "How does that affect the water level?"

The projected volumes of coal moving to port would be enormous--so great, in fact, that the dust alone blowing from open hopper cars would be a major environmental hazard. "If they operate at 99.9 percent perfect, with no mechanical or human error," Julius says, "[Powder River Basin coal producer Peabody Coal] estimates losing one teaspoon of coal dust per ton. That doesn't sound like a lot, but when you multiply it by 48 million, that's 500 tons of coal dust."

The coal ships themselves are the largest oceangoing vessels on the planet--three times the size of those currently operating at Cherry Point. They would have to navigate an archipelago that includes large reefs, major tides, resident orca whales, and an already high volume of ship traffic. An accident could be catastrophic.

In order to proceed, the Cherry Point coal terminal must be approved by Whatcom County, the state's Department of Natural Resources, and, de facto, the tribes. Each is a significant hurdle. In last November's election, candidates presumed to be skeptical of the coal terminal secured a majority on the Whatcom County Council. While they might still approve the project, Floyd McKay, a writer who has covered the issue extensively at Crosscut.com, says, "I wouldn't be surprised if they'll do so with enough restrictions that SSA won't bother." For Peter Goldmark, head of the state Department of Natural Resources, to sign off on the project, McKay continues, he'd have to buck the environmentalist Seattle-Tacoma electorate. Even if he did, the financing may not be there: In January, Goldman Sachs pulled its substantial investment out of the project.

For the tribe, the issue goes beyond coal trains, shipping terminals, and even the fish themselves. "It is not only going to impact our Native treaty rights and reef net sites but also sacred ground," Julius says, referring to Washington's designation of Xwe'chieXen as both an archaeological site and a state historic place.

Last fall, James and the native carvers from the House of Tears fashioned a 22-foot-tall totem pole for spiritual healing. He and a team of tribal diplomats and young carvers loaded the pole on a truck and drove it along the proposed coal route, from Wyoming's Powder River basin across traditional Northern Cheyenne lands, homestead ranches, rivers, and farms, arriving at last in Lummi country. A moon face atop the pole symbolizes both the harvest and its attendant ceremonies, designed to show respect for the fact, James explains, that "something is dying for you." Below the moon, a wolf holds a salmon, symbolizing salmon returning to the Fraser River. Near the bottom of the pole, human figures crouch on bended knee. James got the idea from Amy George, a Tsleil-Waututh Nation elder and daughter of famed actor Chief Dan George, who implored her Canadian tribe to oppose a ramping up of tar sands oil exports from the Fraser Surrey Docks terminal.

"She asked the men to stand up, to quit sitting back. 'When are you going to stand up for your children and their future?' she asked. 'It's time to warrior up!' So that's what the kneeling men are about. They are still passive; they need to warrior up," James says.

If the warriors are successful, 500 years from now, ooligan and herring will still dodge stalking coho among the kelp beds at Xwe'chieXen. Mergansers and herons will patrol the tide lines. A Lummi fisherman, standing tall against blue-green waters, will throw a reef net anchor off his platform, raise the net to the surface, and welcome the first salmon.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club