Falling Stock

As renewables get cheaper and climate risks grow, Wall Street sours on the coal industry

The 500-foot exhaust stack of the Mohave Generating Station in Laughlin, Nevada, was felled by explosives on March 11, 2011. | Photo by John Gurzinski

The once-mighty U.S. coal industry is tottering. The precariousness of its position can be seen in the decision this May by Stanford University’s Board of Trustees to stop investing the school’s endowment in coal-mining companies. While some criticized Stanford for not divesting from all fossil fuels, the fact that ditching coal was such a no-brainer for the school showed how ready coal’s towers were to topple. (See “Financial Statement.”)

Stanford’s divestment decision is part of a less heralded but deeper trend that has been growing for the past year: Traditional investors, including Wall Street equity firms, sovereign wealth funds, pension funds, and other institutional investors that control large amounts of capital, are quietly moving away from coal, thus driving down industry stock prices and reducing the industry’s accustomed sources of funding. (See chart below.) Worse for the coal industry, these financial movers are motivated not by their consciences but by their bottom lines.

Stockbrokers, fund managers, and day traders make their investment decisions based on hard-nosed measures of risk and return—on value, that is, not values. And those decisions are increasingly going against investing in coal.

Coal producers and big utilities with major fleets of coal-fired power plants are getting hammered on multiple fronts. The fracking revolution has made natural gas competitive with and often cheaper than coal. U.S. coal-fired plants are aging, even as the price of power from renewable sources, particularly solar energy, nears “grid parity”—i.e., equality to the cost of electricity from conventional, fossil fuel sources. Though coal produced half of all U.S. electricity from the post–World War II era up through the turn of the century, by 2013 its share had fallen to 39 percent. And the Obama administration’s June 2 proposal to limit CO2 emissions from existing coal-fired plants further dims coal’s prospects.

“Over the long term,” Moody’s Investor Service wrote in a research note, the new emission regulations “would lock the U.S. coal industry into a steeper secular decline than it faced already.” The rule “would almost certainly mean more coal plant retirements and an even greater decline in the power sector’s reliance on coal, reducing coal’s share of power generation closer to 30 percent over the next decade.”

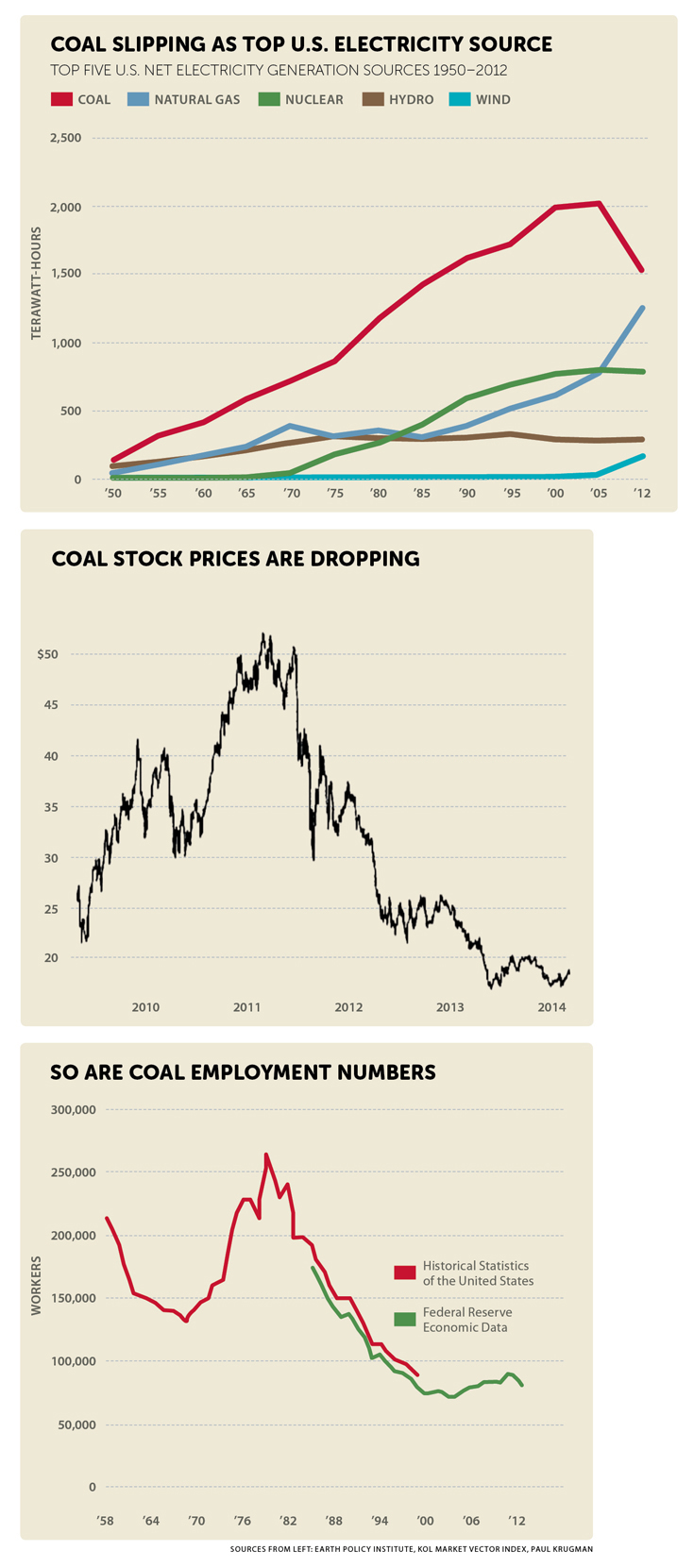

Wall Street likes a winner, but these three charts show an industry in decline. Coal is still the country’s top electricity source, but natural gas and renewables are providing ever larger shares. Coal’s decline is also reflected in the industry’s stock prices and the number of people it employs. “The war on coal already happened,” concludes New York Times columnist Paul Krugman, “and coal lost.”

Anti-coal activists haven’t traditionally based their arguments on financial considerations. The Sierra Club’s Beyond Coal campaign, for example, emphasizes the public health risks from soot, mercury, and coal ash, while the campus divestment movement leans more heavily on coal’s leading role in global warming. Together, says Bruce Nilles, Beyond Coal’s director, “we’re fundamentally changing the way we power the country. It’s a feat that never would have been possible without the anti-coal movement changing the public discourse through lawsuits, grassroots activism, licensing hearings, and lobbying.”

That traditional activism paid off last October, when the board of the San Francisco Employees’ Retirement System voted unanimously to explore divesting all fossil fuel stocks from its portfolio. As you might expect from a city filled with climate activists, the move had a strong moral component: “How do you want to be seen by future generations?” city supervisor John Avalos asked during the meeting at which the vote was taken.

But the managers of the $16 billion pension fund could also rest assured that their decision carried little if any financial risk. They cited a 2013 report by the Aperio Group, a Marin County financial advisory firm, which found that fossil fuel divestment wouldn’t introduce significant new risk to the fund’s portfolio. The risks of investing in fossil fuels, on the other hand are high and getting higher.

A November 2012 report from the Union of Concerned Scientists concluded that it’s up to utilities, regulators, and banks to decide “whether it makes more economic sense to retire certain coal-fired generators, and potentially replace them with cleaner energy alternatives, instead of sinking hundreds of millions—and in some cases billions—of dollars in additional capital into retrofitting them with modern pollution controls.”

A May 2014 study from the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis bluntly advised that New York City’s and New York State’s pension funds divest from coal stocks: “The current position of the U.S. coal industry, and increasingly that of coal producers worldwide, is weak. And the worst is yet to come. U.S. coal company leadership has no effective investment rationale for improving stock performance. . . . Selling the stock would actually put the money to more profitable use and better protect the beneficiaries of the funds.”

From 2010 to 2012 alone, 145 coal-powered generators were retired or slated to be retired (many through the efforts of the Club’s Beyond Coal campaign). Another 413 generators, representing 60 gigawatts of capacity, could be gone by 2020, according to the Energy Information Administration’s latest projections. Coal, with its declining share of the U.S. power market, isn’t where long-term investors want to put their money. Wall Street, which responds more quickly to market trends than do pension funds and university endowments, lost its appetite for coal stocks years ago. Since late 2012, Peabody Energy’s stock value has fallen by 28 percent, while its rival Arch Coal’s has dropped by 42 percent.

“The window to invest profitably in new mining capacity is closing,” Goldman Sachs commodities analysts wrote in a July 2013 report. “Earning a return on incremental investment in thermal coal mining and infrastructure capacity is becoming increasingly difficult.”

That has not deterred Peabody CEO Greg Boyce, who said in an interview at his St. Louis office in January that his industry’s current woes are just another turn in its historic cycle of boom and bust. Demand is rising in the developing nations of Asia, he said, particularly India and China (which, together, will account for three-quarters of the new coal-fired generation capacity added worldwide over the next decade, according to the World Resources Institute). This means that “there is going to be a deficit in supply,” Boyce asserted. “We are looking at when is the right time, and what are the right projects to begin the next investment tranche, so that we can participate and benefit from a rising price environment.”

Don’t count coal out, Boyce said: “To compete in the global economy, we need competitive, affordable energy that is based in this country. And it needs to be done by coal.”

Where Boyce sees growth potential, others see increasing risk—to the economy from climate change, and to investments in coal, the largest single driver of planetary warming. The first danger was highlighted in June by the Risky Business Project, a collaboration between former New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg, billionaire climate activist Tom Steyer, and Henry Paulson Jr., treasury secretary under George W. Bush and former CEO of Goldman Sachs (Bloomberg and Steyer have donated money to the Sierra Club through their charities.).

“I know a lot about financial risks,” Paulson said in a video interview. “In fact, I spent nearly my whole career managing risks and dealing with financial crisis. Today I see another type of crisis looming—a climate crisis. And while not financial in nature, it threatens our economy just the same.”

Europe is taking that risk very seriously. Storebrand, a major life insurance and pension fund firm in Norway, announced in July 2013 that it was pulling its money out of coal and tar sands companies—not only because its clients demanded action to limit climate change but also because it believed that stakes in those companies would be “financially worthless” in the future.

“It was a fairly technical decision, really,” says Christine Tørklep Meisingset, head of Storebrand’s environment, social, and governance research. “Coal and oil sands have too high a risk based on low performance from a sustainability and long-term-risk analysis.”

Storebrand and other large European investment firms, such as Paris-based Kepler Cheuvreux, have adopted what’s known as the “carbon bubble” analysis of global energy markets. “The valuation of fossil fuel companies is largely defined by reserves,” Tørklep Meisingset says. But since two-thirds of known coal, oil, and gas reserves will have to stay in the ground to limit global temperature increases to an acceptable level, “being in the high-carbon end of the scale may prove a very risky investment.” The risk to these companies is that fossil fuels left in the ground will become “stranded assets”—never able to be utilized, and thus worthless.

The idea of the carbon bubble was first popularized in a 2011 report by the Carbon Tracker Initiative. Last year’s update to that report calculated that the total listed reserves of the world’s fossil fuel companies represent 762 gigatonnes of CO2—only 20 to 40 percent of which can be emitted into the atmosphere for human society to avoid catastrophe.

“The scale of this carbon budget deficit poses a major risk for investors,” wrote the report’s authors, Jeremy Leggett and Mark Campanale. “They need to understand that 60-80 percent of coal, oil and gas reserves of listed firms are unburnable. . . . Capital spent on finding and developing more reserves is largely wasted. To minimize the risks for investors and savers, capital needs to be redirected away from high-carbon options.”

That’s not a moral judgment, says Bob Litterman, who chairs the risk committee at Kepos Capital; it’s smart financial strategy: “The idea that you want to hedge stranded assets and dirtier types of fuel like tar sands and coal is essentially a bet that prices on emissions will be created sooner and higher than are currently built into expectations. Some of us think that’s a good bet.”

It’s important to realize that this bet is not predicated on specific government policies, such as a tax on carbon in the United States or a global cap on emissions. It’s simply a wager that the costs of continuing to spew CO2 into the atmosphere will become more evident—and less supportable—as the earth rapidly warms.

That bet became easier to make last April, when FTSE, a firm that develops equity indexes for various industrial sectors, created the first large-scale, publicly available index that explicitly excludes fossil fuel companies. Developed in conjunction with the Natural Resources Defense Council and U.S. investment house BlackRock, the index will serve investors “looking to manage carbon exposure in their investments, and reduce write-off or downward revaluation risks associated with stranded assets.” It will be valuable not only for investors who have already made the decision to divest from fossil fuel companies, says FTSE managing director Kevin Bourne, but also for those still on the fence.

“Unless and until they are forced to divest, it’s clear large investors will not,” Bourne says. “Now they’ll be able to track what would have happened if they were not invested in fossil fuels. We’re fielding a lot of inquiries from large pension funds that are not looking to divest immediately, but to research and understand what would have happened if they did.”

It’s a short step from examining what might happen if you divest to actually divesting—and the pressures on big funds to get out of dirty fuels and “invest in sustainable solutions,” as Storebrand’s Tørklep Meisingset puts it, are only going to grow. The FTSE index excludes all fossil fuels, and the larger divestment movement doesn’t always distinguish between coal and petroleum. Coal, though, carries risks that are different from and, in some ways, greater than those of oil and gas.

For one thing, coal mining, although less capital-intensive than drilling for oil, is a brute-force enterprise. There are no technological innovations on the horizon that will make coal extraction cheaper, or open up large new reserves that were previously inaccessible or uneconomic. You can’t frack coal.

And unlike oil, coal is readily replaceable. There are few substitutes for petroleum in transportation applications like aviation, but substituting renewable energy for coal to produce electricity is feasible and increasingly economical. In Iowa, for example, wind energy grew to account for nearly 25 percent of the state’s electricity generation from 2006 to 2012, while coal’s share fell by 12 percent over the same period.

Finally, coal is associated with black lung disease, horrific mining disasters, and mountaintop removal, and carries a stigma that even crude oil does not. What has happened with the coal industry in the past several years resembles the public disaffection with tobacco a few decades earlier: Once a ubiquitous part of modern life, coal is becoming something to be shunned. As that process advances, the contraction of the industry will follow very quickly. Coal is increasingly seen as your grandparents’ fuel, and if, in the 21st century, you continue to put your money into it, your grandchildren are going to wonder why you did.

“I was a risk manager on Wall Street for many years, and our job is to think about worst-case scenarios,” Litterman says. “With climate change, we don’t know what the worst case is. I think the investment community has only begun to take that into account.”

In the end, considerations of values and value merge. After all, what is concern for the future if not perception of risk? At the San Francisco hearing on divestment, a pensioner put it succinctly. “Your duty is to protect the benefits of retirees like me,” Jack Fleck, a retired San Francisco transportation engineer, told the supervisors. “How can it be to my benefit if the very climate is being destroyed?”

This article was funded by the Sierra Club’s Beyond Coal campaign.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club