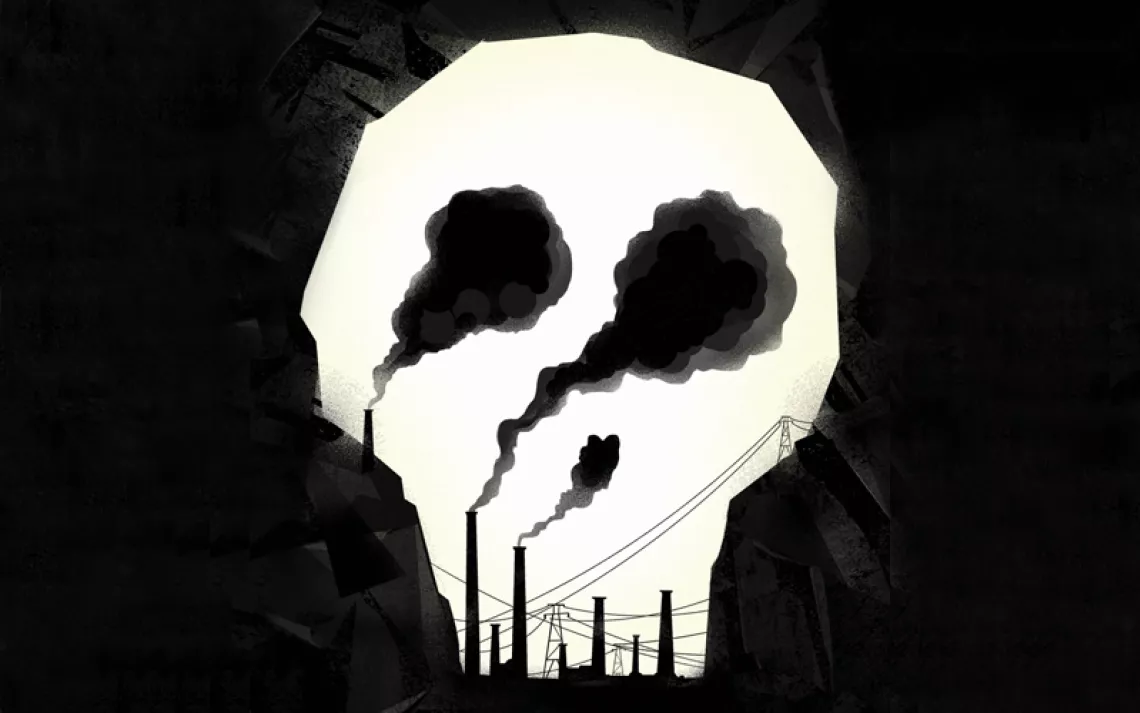

The Olive and the Power Plant

Turkey's rush to build coal plants comes at the expense of its most beloved culinary ingredient

Olives are central to the cuisine and culture of Yirca, Turkey. | Photo by Umut Vedat/Greenpeace

FOR SEVEN WEEKS IN THE FALL OF 2014, the villagers of Yirca kept watch over their olive groves day and night, warming themselves around a fire and taking turns sleeping in a small shelter. Sentinels with binoculars were stationed under the pines on a nearby hill with a sweeping view across the broad, flat valley. They were scanning for any sign of movement by the Kolin Group, the company that was seeking to expropriate this land to build and operate a 510-megawatt, coal-fired power plant.

"If the scouts saw anything, they'd get on their phones and call down, 'The bulldozers are coming!' and the people would rush to block the road leading to the groves," says Mustafa Akin. The avuncular former teacher now serves as muhtar—the elected village head—of Yirca, a tiny settlement of 400 in western Turkey, 50 miles inland from the Aegean Sea.

For a time, despite several confrontations with Kolin Group workers, the villagers' vigil was largely successful. But one night in early November, the bulldozers came back, this time accompanied by two busloads of private security guards and a "rapid expropriation" order from the government. Arguments broke out, and then scuffles. Four people were hauled off in handcuffs; others say they were beaten by the guards. Before the sun rose, 6,000 olive trees had been ripped out of the ground.

"We had a hundred people trying to keep the bulldozers from coming in, but we couldn't stop them. It was an awful feeling," says Akin, looking out over the desolate field still ringed by barbed wire. Six months after the incident, he is calm and composed, but the day after the tree cutting, Akin broke down on camera while describing the event to Turkish news crews. "Surely those who did this eat olives. They use olive oil on their dinner tables," he said, tears welling in his eyes. "How can they eat olives now?"

Olive trees in Yirca, Turkey, bulldozed by the Kolin Group, with a coal-fired power plant in the background. | Photo by Umut Vedat/Greenpeace

SCENES OF RURAL VILLAGES TRYING TO defend their land and livelihoods are becoming more frequent as Turkey pushes to develop domestic energy resources—with a heavy emphasis on coal—to meet growing power needs and reduce its reliance on imported natural gas from Russia, which currently accounts for more than half of Turkey's gas imports. According to estimates by Bloomberg New Energy Finance, Turkey's plans for "a coal-led expansion of its power generation . . . would involve a 145 percent increase in coal-fired generation and a 94 percent jump in power-sector emissions" by 2030. Much of Turkey's coal is low-grade lignite, which burns even dirtier than the hard coal commonly mined in Appalachia.

With two coal-fired power plants already in their neighborhood, Yirca residents had a good idea of what the new one would bring. While showing a visitor around the area where the villagers kept their weeks-long vigil, Akin points to a nearby ridge; behind it sits an open landfill for coal-ash waste. "When the wind comes, the ash covers everything—our village, our gardens, our olive groves," he says, adding that construction of a third power plant would also require a new ash landfill. "This was the thing we wanted to fight most of all."

Akin's wife, Hamide, agrees, rattling off the names of neighbors who have been diagnosed with cancer, her list interrupted by a persistent cough she says she hasn't been able to shake for weeks, despite repeated visits to the doctor. According to Physicians for Social Responsibility, exposure to coal ash can increase the risk of cancer, respiratory illnesses, and other diseases.

Some economists believe that additional coal plants, like the one for which Yirca's 6,000 trees were sacrificed, are not even necessary. "Turkey could have the highest potential for solar [power] in Europe in terms of the sun hours it gets, over quite a big landmass," says Itamar Orlandi, an analyst with Bloomberg New Energy Finance. "But renewables get a low amount of support from the Turkish government, and the prohibitive cost of planning and permits in Turkey compared to other places in Europe is holding the market back." A white paper he coauthored in November 2014 showed that Turkey could meet its energy needs by ramping up renewables (including hydropower) at a cost only marginally higher than that of its current coal rush.

Renewables are already part of Turkey's energy mix, but the vast majority is hydropower, which has its own set of problems. Proposed and under-construction hydro facilities have been protested, often in vain, for the threats they pose to natural areas, wildlife habitats, archaeological sites, and the homes and livelihoods of rural residents.

But as environmentally damaging projects have multiplied across Turkey in recent years, so has solidarity among those affected, strengthening the country's nascent environmental movement. The villagers in Yirca, for example, were supportedin their fight by activists from the Mount Ida region, near the ancient city of Troy, where gold-mining companies are encroaching on olive groves and open space. Also rallying for them were activists from Canakkale, near the famed Gallipoli battlefields of World War I, where at least 11 coal-fired power plants are in the works, and from Istanbul, where a new airport, bridge, and roads are cutting through vast swaths of forest north of the city, often thought of as the lungs of the crowded metropolis.

"When the government sees a short-term benefit, it completely ignores the social and environmental cost," says Salih Madra, founding president of the Ayvalik Olive Producers Association and a third-generation olive grower. (Madra's family came to the Aegean town of Ayvalik from the Greek island of Lesbos in the early 1920s.) He is at the center of a campaign launched last year to protect small olive growers—already struggling with the effects of climate change and competition from better-subsidized European growers—from what he calls the disaster of a legislative push to allow coal plants and other polluting facilities to be built on or near olive groves.

Activists deliver saplings to replace the 6,000 olive trees that were uprooted to build a power plant in Yirca, Turkey. | Photo by Umut Vedat/Greenpeace

TURKEY IS THE WORLD'S SECOND-LARGEST producer of table olives and fourth-largest producer of olive oil. Both items are close to its culinary and cultural heart. Olives have been cultivated in the eastern Mediterranean for at least 6,000 years; their pits have been found in the cargo holds of sunken Byzantine-era trading vessels, and their oil was used to light the lamps of Constantinople's great basilica, Hagia Sophia.

Today, says food writer Aylin Öney Tan, olives are a must-have at the Turkish breakfast table and in the iftar meal, which breaks the Ramadan fast. Likewise, she says, "there's a whole category of zeytinyaglilar—vegetable dishes cooked with olive oil and served cold—that are a staple of many people's diets." Turkish consumers, she says, are also rediscovering the distinct tastes of early-harvest oils and those from different growing areas. "Usually the taste of olive oil from the north of Izmir, especially the bay around Ayvalik, is considered more delicate, more fruity and grassy," says Tan. "When you go south along the Aegean coast, you get a more oily, earthy, robust, bold flavor."

The olive's primacy in the Turkish kitchen is reflected in its legal standing, explains olive grower Madra: "Turkey has had a law since 1939 protecting its olive trees, which were being left uncultivated after World War I and the demographic upheaval caused by the 1923 population exchange between Turkey and Greece." (As part of a treaty between the then-warring countries, some 2 million people were forced to relocate, with Christian citizens of Turkey sent to Greece and Muslims in Greece sent to Turkey.) This law was strengthened in 1995 to ban construction of polluting facilities within 3 kilometers (1.9 miles) of olive groves. Since then, the number of olive trees in Turkey has nearly doubled, to 167 million, or more than two trees for every person in the country.

But over the past decade or so, industry has tried to remove these protections through regulatory or legislative changes to the olive law. Most recently, the government proposed legislation in the Turkish Parliament to exempt olive groves smaller than 2.5 hectares (about 6 acres). Since the average Turkish olive grove is only 1.2 hectares, such a change would leave thousands of small growers at risk of losing the trees they have tended for decades.

ON A WARM AFTERNOON in early May, the smell of chicken manure hangs heavily over the small olive groves remaining around Yirca. Following an unseasonably wet spring, the tiny village has emptied out as its residents spend their days in the surrounding fields, pruning their trees with handsaws and shears and burning any trimmed branches that haven't been gathered as fodder for livestock. At midday, Hamide Akin spreads a tablecloth and a couple of flat-woven kilim rugs in a shady spot among the trees. She lays out bowls of buttery pilaf, shepherd's salad, and vegetable-and-mincemeat stew, then opens up containers of olives—the green ones tangy and lemony, the black ones meaty and just salty enough. She pours olive oil from a plastic Pepsi bottle over a dish of spicy tomato paste. After lunch, she heats tea in a blackened kettle over a wood fire, keeping it warm over the coals while serving.

"We have three meals a day out here during the fall harvest season," says Mustafa Akin, explaining in between bites of lunch that one person can hand-harvest the olives from four or five trees a day, working from morning to night. Growing olives isn't easy work, he admits, but few people in Yirca want to abandon their fields for the alternative of toiling in the area's coal mines. (In May 2014, 301 people were killed in the Soma mine, Turkey's worst-ever industrial accident.)

A few olive trees cut down last fall still lie where they were felled, the fields around them now blanketed with tall grasses, yellow wildflowers, and bright-red poppies. The grove is still fenced off, but there's no sign of construction. Just hours after the trees were uprooted, Turkey's highest administrative court ruled in favor of the Yirca villagers, saying that the cabinet decision allowing the Kolin Group to expropriate the land was illegal, because the law protecting olive groves had not yet been changed.

"Companies here don't wait for court decisions," explains Madra. "If they feel the government is behind them, they just go on [with their plans]."

In late spring, Kolin announced that it had found a different location in the area for its power plant. Then, following a national petition driven by the Turkish branch of Greenpeace, in addition to the campaign started by Madra, the country's parliament adjourned for the summer without taking up the bill that would remove the protected designation for small olive groves.

"In Turkey, justice comes after [the fact]," laments Mustafa Akin. Still, he says, the villagers feel proud that they were able to win against such a large company, especially one whose plans were backed by the government. Once the court case brought by the villagers and Greenpeace has been finalized, he says, the people who lost their trees plan to seek compensation, though their chances of success are unclear. The Kolin Group has opened its own case against two dozen Yirca villagers who stood guard over the groves last fall, on charges of property damage for their attempt to block the power plant's construction.

Though the victories were bittersweet for Yirca, they were celebrated in the village and by olive growers elsewhere. But few expect them to be permanent.

"The government has tried to alter this law so many times," says Madra. "Olive growers won in the courts when [the government] tried to make a regulatory change through the agriculture ministry, and then it tried again, this time through the energy ministry. It's both tragedy and comedy. Unfortunately, we have to be always alert."

This article was funded by the Sierra Club's Beyond Coal campaign.

Take a Sierra Club Outings Trip

Take a Sierra Club Outings trip to Turkey. For details, click here.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club