Building an Indigenous Response to Environmental Violence

Photo by iStockphoto/weerapatkiatdumrong

Our bodies are in sync with the earth. For many indigenous people living in North America, there is a strong connection between the health of the lands they inhabit and their bodies. As extractive industries (such as fracking, mining, and drilling) continue to remove natural resources from the land without consent from the people who live there, indigenous communities are taking a new approach to halt their efforts.

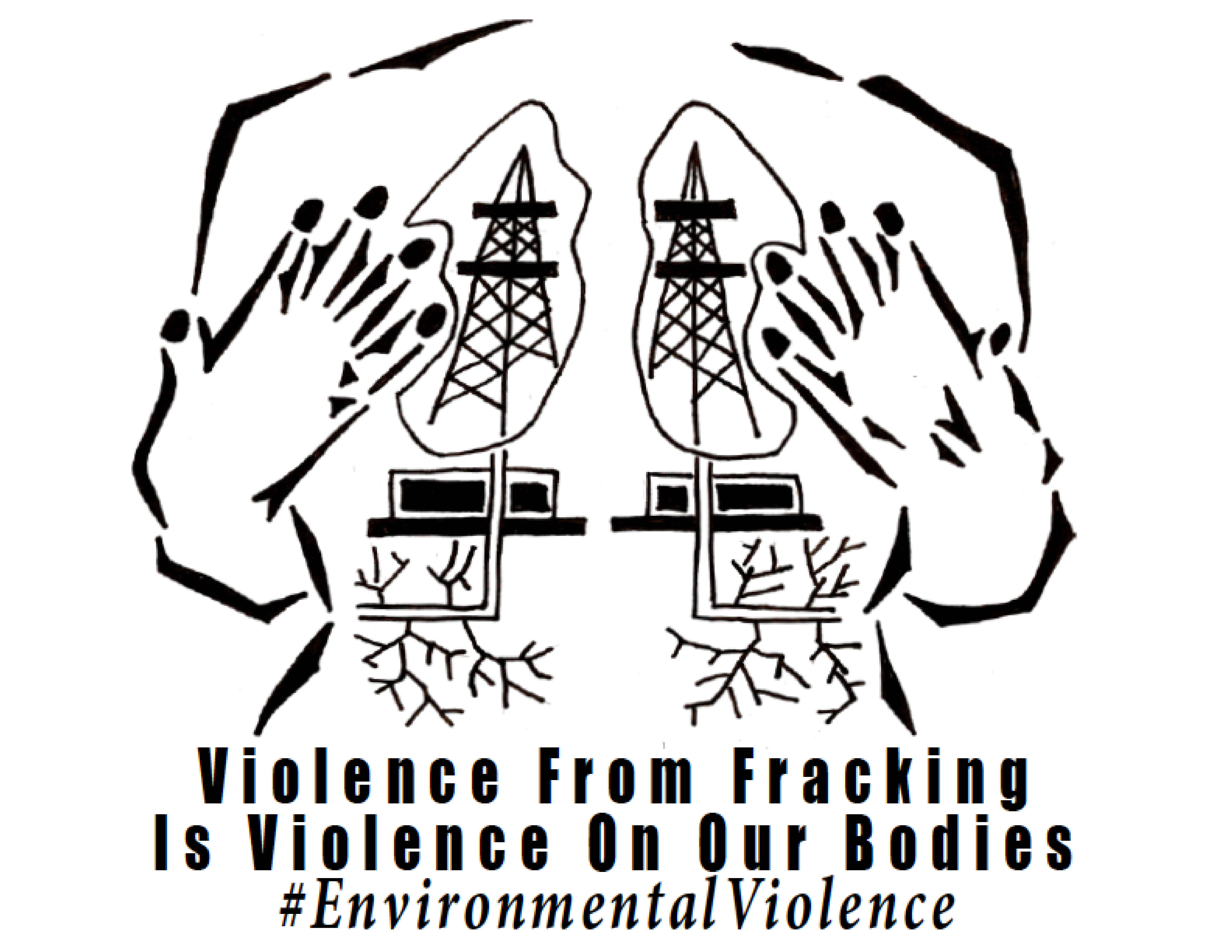

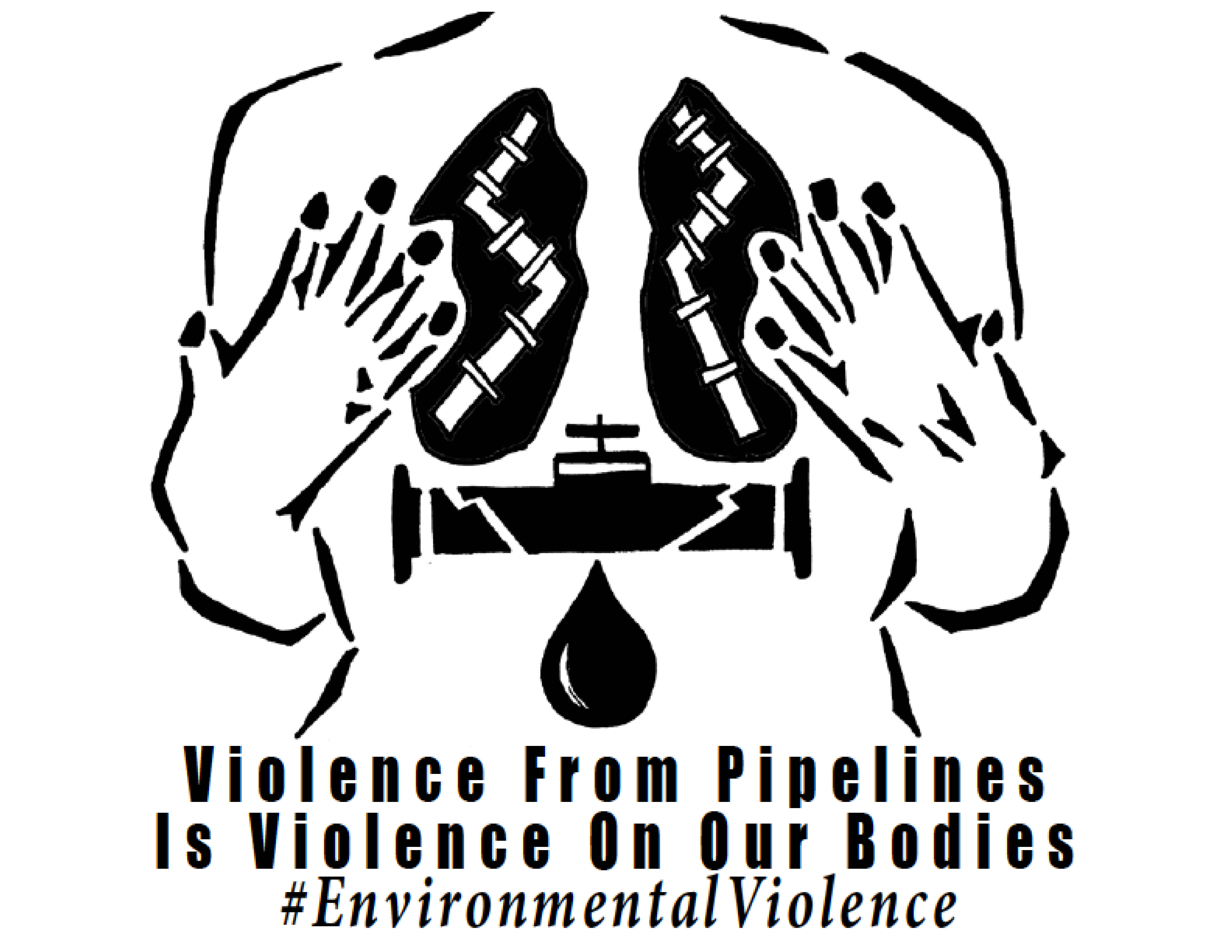

Last week, Women’s Earth Alliance (WEA) and Native Youth Sexual Health Networks (NYSHN) launched the Violence on the Land, Violence on our Bodies community-based research initiative. The report and toolkit highlight the fact that many indigenous women and youth are disproportionately affected by the poor treatment of the planet. In the United States alone, approximately 5 percent of oil, 10 percent of gas reserves, 30 percent of low sulfur coal reserves, and 40 percent of privately held uranium deposits are found on Native American reservations.

This violence against the land is often accompanied by physical and sexual violence against indigenous women and young people. The two are interconnected and collectively referred to as environmental violence, which the report defines as “the disproportionate and often devastating impacts that the conscious and deliberate proliferation of environmental toxins and industrial development (including extraction, production, export and release) have on indigenous women, children, and future generations.

This violence against the land is often accompanied by physical and sexual violence against indigenous women and young people. The two are interconnected and collectively referred to as environmental violence, which the report defines as “the disproportionate and often devastating impacts that the conscious and deliberate proliferation of environmental toxins and industrial development (including extraction, production, export and release) have on indigenous women, children, and future generations.

In the United States, Native American women experience sexual violence at a rate that is 2.5 times more than that of any other group of women. In 2009, Alberta, home to the Tar Sands Gigaproject (the largest industrial project in history), had Canada's highest rate of domestic violence. “It is not enough to defend the land,” says Erin Marie Konsmo, the Media Arts Justice and Projects Coordinator for the NYSHN. “Women are going missing and being murdered in our communities.”

The report provides a safe place for indigenous communities to tell their stories and inspire others to take immediate action. It also challenges the policies, practices, and legislation that have marginalized indigenous people and allowed them to continually be exposed to life-threatening toxins.

Chelsea Sunday, a member of the Akwesasne Mohawk Nation near the U.S. northeastern border, describes how she participated in a study as an adolescent to determine whether the chemical waste dumped upstream affected the health of community members. Now a mother of two, Chelsea worries for her children's future.

April McGill, an indigenous woman from Northern California, discusses her battle with cancer and relates it to Mother Earth’s ongoing suffering. As a young girl, she learned from her grandmother about the sacredness of the body and the land. “We’re going through so many things with our bodies—sexual violence, environmental violence—and we’re feeling that from our Mother, too.” Stories like these emphasize the connection between environmental toxins and health problems like cancer and infertility and demonstrate the resilience of indigenous communities in the face of environmental abuse.

The toolkit provides activities that promote dialogue and healing. One exercise instructs participants to pick an element in the surrounding environment and then identify that element and its direct relationship to themselves without giving it a gender. For example, “This is river. It is made up of water. The river provides us with water to drink. My relationship to water is….” Another activity calls for participants to break off in small groups to discuss a given quote. After a few minutes, they return to the larger group and define what consent of the land/body means to them.

Sharing personal experiences is crucial to the healing process, but the information in the report is not just for indigenous communities. Kahea Pacheco, the Programs and Operation Manager at WEA,states,“The biggest things allies can and need to do is listen more to the folks in these communities who know firsthand what their lands and bodies experience, and will also know how they can best be supported."

This article has been modified since its original posting.

WHAT YOU CAN DO

Take the time to read through the report and toolkit. In conjunction with the launch of the research initiative, last week was named Week of Action to help spread the message about the ruinous effects of extractive industries. The hashtag #landbodydefense was generated to encourage participants to share a message or photo of themselves touching the earth. Though the Week of Action has ended, you can still share the hashtag and a message of support through social media.

SEND A MESSAGE

Protect Our Climate. End Fossil Fuel Leasing from Under Our Oceans & On Public Lands -- We have to keep the vast majority of dirty fuels in the ground, unburned, in order to prevent the worst impacts of climate disruption. Take action today to end fossil fuel leasing on our public lands.

Take Action: Protect Public Lands and Our Climate from Big Coal -- 40 percent of US coal comes from public, taxpayer-owned land. Now, the government is studying how that coal impacts our climate. We have an unprecedented chance to push for a clean energy future.

Tell Your Senators to Say NO to Arctic Drilling! -- Tell your senators to keep Big Oil out of the Arctic.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club