Great Gull Island

A Photo Essay

Photographs courtesy of Erik Hoffner

“KEEAR KEEAR, the terns are coming!” read the opening line of an email sent to the Great Gull Island Project volunteers last spring, as thousands of shrieking seabirds arrowed in on a 17-acre-island just off the tip of Long Island, New York. Once the site of a Spanish American War-era fort and now a biological research station owned by the American Museum of Natural History, it’s home to the world’s largest nesting population of common terns (considered a threatened species) and also roseate terns (endangered).

Just as the birds descend on this low-slung island from their far-off winter homes, so too does a corps of volunteers; volunteers have been aiding the study of the tern rookery since the project’s inception in the mid-1960s. Roosting in the old brick barracks, wearing wide hats brimming with tall sprays of plastic flowers to keep the dive-bombing terns at bay (their swoops can end with a sharp peck to the head if not warned off), they march across the island ticking off the location of nesting tern pairs carpeting the ground and on crumbling gun turrets. All this is at the direction of lead researcher Helen Hays, who has lived on the island for the entirety of each breeding season since 1969.

Hays (now 80 years young) has watched the common tern colony grow to 9,500 nesting pairs. She and her colleagues have discovered much about the birds, including the location of their winter home in Brazil.

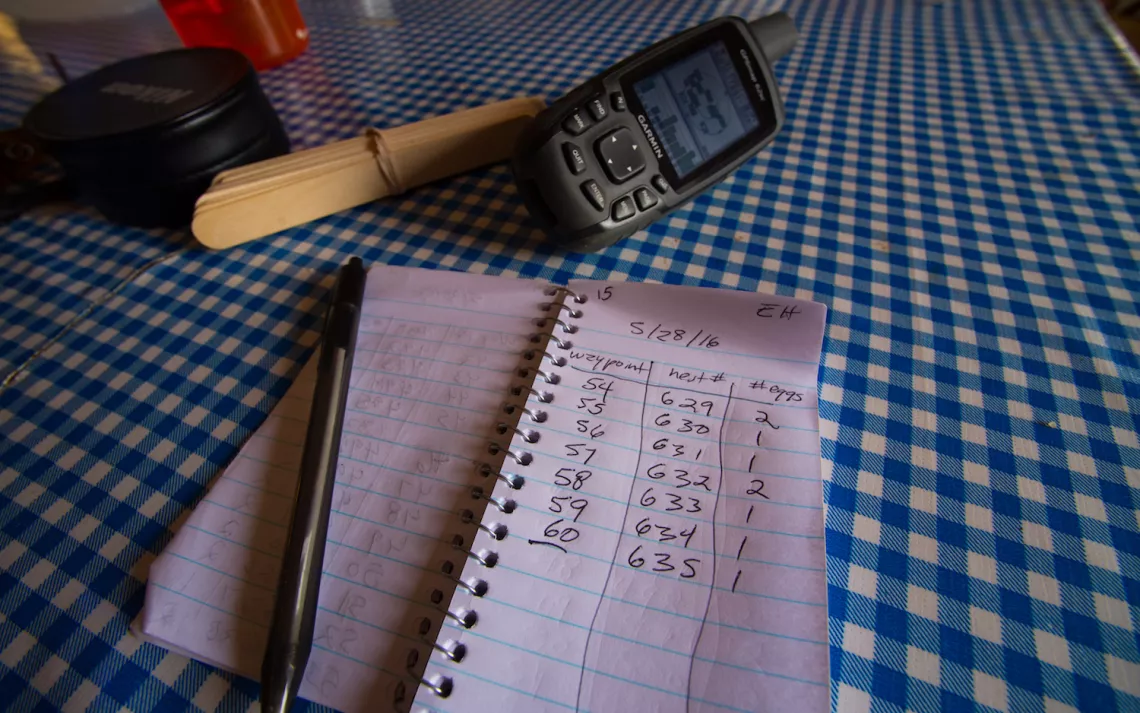

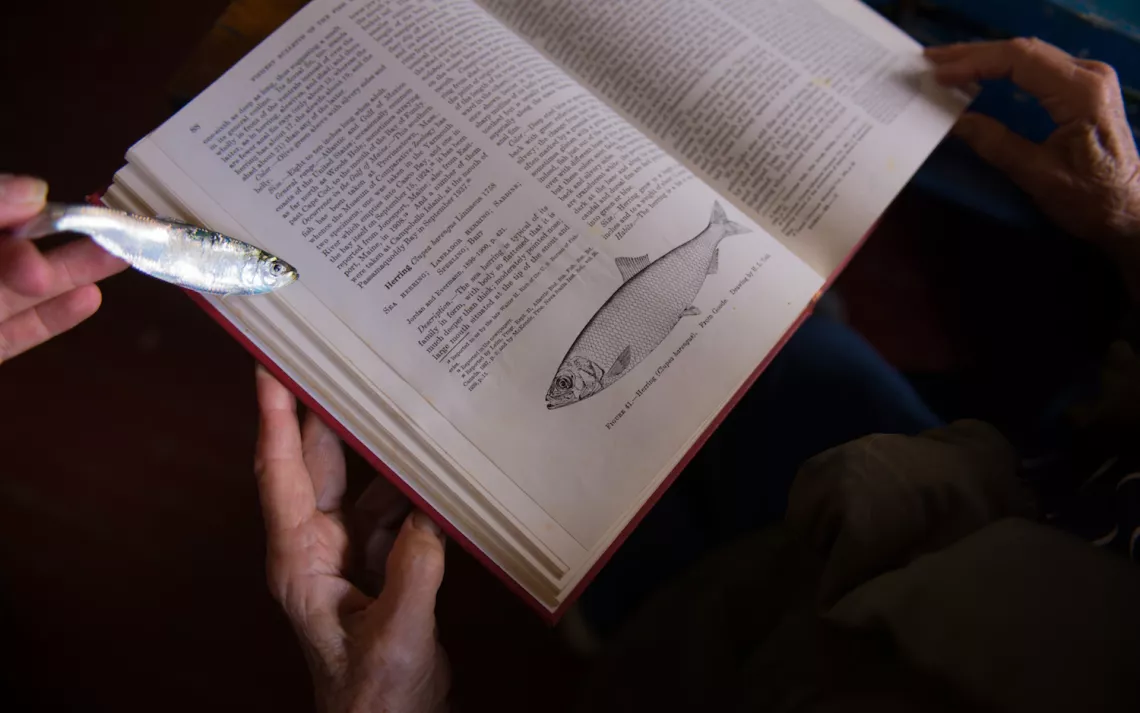

On a recent weekend, I joined a group of almost a dozen volunteers—from recent college grads visiting for the first time to others who’ve been involved since the 1980s—in an effort to document every tern nest on the island. Working in zones with GPS units and notebooks in hand, we crept carefully along, recording each spot and the number of speckled eggs while angry terns chattered and attacked from above. The news was good, with 2,000 new nests marked since the previous weekend’s volunteers were out, and with the promise of many more yet to be established—the birds were finding anchovies, sand eels, and herring in abundance in the Long Island Sound waters.

As the colony grows each year, so does the urgency to band the chicks, so that their life stories can become part of Great Gull’s vast volume of data. In probably the world’s best and biggest long-term study of these tern species, researchers use these data points to unravel all kinds of mysteries, including how old the birds live to be. Two snowy owl pellets found by our group, when pulled apart, revealed the leg bands of two early-returning—and ill-fated—common terns aged 15 and 18 years.

Imagining their yearly travels to and from Brazil (and perhaps to the Azores and back, too, as Hays’s team has also documented) for so many years sent a thrill of appreciation through all assembled in the research station HQ. These intrepid birds lived well.

The Great Gull Island Project relies on volunteers to collect data on the tern colony between May and September each year, with a special need during July when the team is banding chicks. Learn how to get involved here.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club