Rigging the system to keep us using dirty energy forever

Big Coal may be dying, but it's still trying to strangle clean energy in the cradle

Illustration by David Plunkert

When President Barack Obama and EPA administrator Gina McCarthy released the final regulations for the Clean Power Plan in August 2015, it was a defining moment in the fight against climate change. The plan established the first-ever national standards for limiting carbon pollution from power plants, which are the nation's single largest source of greenhouse gases. And it did so in an act of political jujitsu, sidestepping congressional gridlock by using the regulatory power of the Clean Air Act. The CPP requires states to develop plans for reducing carbon emissions from power plants by 32 percent by 2030, using 2005 emissions as the baseline.

States can meet their targets using a variety of means--employing increased efficiency, renewables, natural gas, or nuclear power. While the rules create many potential winners, there is one clear loser: coal-fired power plants. An analysis by the U.S. Energy Information Administration found that under the Clean Power Plan, coal's share of U.S. power generation would decline from 33 percent in 2015 to 18 percent in 2040. Without the CPP, coal might still account for 26 percent of U.S. electricity generation in 2040.

Coal is already in decline, with 41 coal-fired power plants retiring from the grid so far this year and no new ones in the works. Low prices for natural gas and increased investment in renewables, combined with more regulation of coal-generated pollutants, have made the black rock increasingly unappealing to utilities and their investors.

But the coal industry isn't going down without a fight. And when industry wants to obstruct environmental regulations in statehouses across the nation, it calls on the American Legislative Exchange Council.

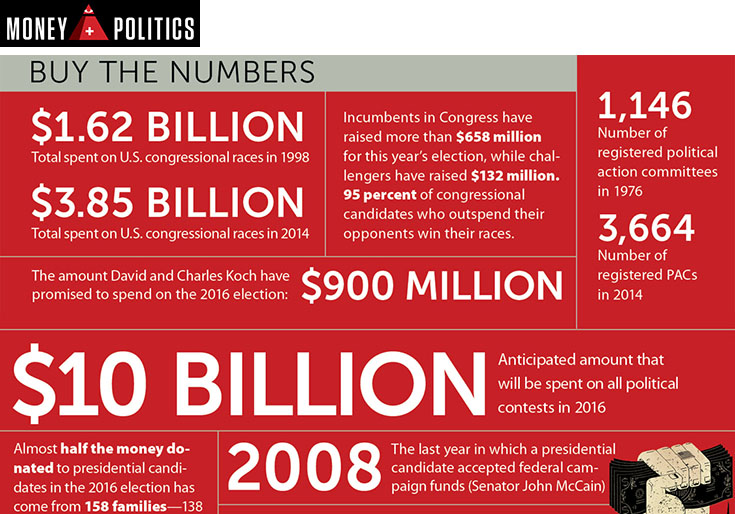

Founded in 1973, ALEC is a kind of dark-money dating service, matching wealthy corporations with compliant politicians. Based in Arlington, Virginia, and underwritten by fossil fuel interests like Koch Industries, ExxonMobil, Peabody Energy, the American Coalition for Clean Coal Electricity, and Dominion Resources, ALEC crafts templates for legislation that reflect the desires of its funders, and then puts those bills in the hands of lawmakers. "ALEC has been fighting tooth and nail on behalf of its funders," says Aliya Haq, deputy director of the Clean Power Plan initiative for the Natural Resources Defense Council.

Nick Surgey, director of research for the Center for Media and Democracy, estimates that ALEC's 2,000 elected-official members represent up to one-third of all state legislators and as many as two-thirds of Republican state legislators. These lawmakers sit cheek-to-cheek with corporate lobbyists on ALEC's nine bill-drafting committees--but the lobbyists wield effective veto power.

"They can say that they're legislature-driven," Surgey says of ALEC. "But it's industry-funded. It's the industry agenda. There's nothing that becomes ALEC policy without industry approval."

Over the years, ALEC has produced cookie-cutter legislation designed to weaken unions, restrict access to voting, and thwart regulation of firearms. But its primary focus these days is serving the fossil fuel industry. It has written bills giving climate change deniers a voice in environmental education and drafted legislation opposing state-level renewable energy standards, which set the amount of clean energy states must use. In Arizona and elsewhere, ALEC is trying to stifle the spread of rooftop solar generation (see "Sun Blocked," page 32).

Even before the Clean Power Plan was finalized last year, ALEC's coal-industry funders were attempting to torpedo it, using an army of legislative proxies. The Center for Media and Democracy reported that as early as January 2014--a year and a half before the CPP was finalized--ALEC was already organizing conference calls with its member legislators, asking them to encourage their states' attorneys general to file suit against the plan. Twenty-nine ultimately did so, and in February 2016, the Supreme Court issued an unprecedented order suspending implementation of the plan until there is a final court decision on whether it is legal.

The case will be heard in late September by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, and will almost certainly be appealed to the Supreme Court. (Counter to ALEC, 18 states and the District of Columbia have filed briefs in support of the Clean Power Plan, as have 60 municipalities, 10 utilities, and a number of large companies including Amazon, Apple, Google, Microsoft, IKEA, and Mars.)

The Supreme Court's stay opened the door for further ALEC-led obstruction. A number of states announced that they would continue working on implementation plans regardless, in the event that the regulations are upheld. To forestall this, ALEC has written bills aimed at obstructing all CPP implementation measures. These efforts include restricting funding for state environmental agencies as well as promoting laws requiring state legislatures to approve their state's plan before it can be sent to the EPA. (Such approval is not usually required when state agencies are complying with federal law.)

This type of legislation has already passed in Kansas, West Virginia, and Wyoming, but has failed in most other states where it has been introduced, which is why Haq sees ALEC's efforts to derail the CPP as largely unsuccessful. Most states will continue to develop plans for complying, she says, because they don't want to cede power to the EPA and because many utilities are already planning for a future that doesn't include coal.

But Surgey warns against premature celebration. ALEC's overarching goal, he says, is to prevent the regulation of carbon emissions. Every time one of its anti-CPP bills is introduced in a state legislature, ALEC's message--that carbon regulation is bad for the economy--gets reinforced.

"It's not just about whether a bill gets passed or not," he says. "They play a very long game. It's a battle of ideas and a war of words. For ALEC, it's a 40-year war."

This article was funded by the Sierra Club's Beyond Coal campaign (beyondcoal.org).

This article appeared in the September/October 2016 edition with the headline "Dirty Power Plan."

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club