Climate Neighbors

A new report highlights climate challenges and resiliency on the U.S.-Mexico border

San Ysidro Land Port of Entry in San Diego, California | Photo by Shazku/iStock

According to President-elect Donald Trump, the biggest problem with the U.S.-Mexico border is that it is a violent no-man’s land where illegal immigration runs rampant. But a new report from an independent presidential advisory committee points to a much more real and pressing problem: climate change.

The Good Neighbor Environmental Board—which includes representatives from federal, state, local, and tribal governments as well as environmental groups and universities—warns in a new report that the hot, dry climate typical of the borderlands puts the region at risk for extreme heat events, water scarcity, poor air quality, and the spread of infectious diseases. That combined with a high percentage of low-income residents, many of whom live in substandard housing, makes the region among the nation’s most at risk. The report also outlines concrete steps to build climate resiliency in border communities.

“We are trying to raise awareness that there are very clear and urgent issues to deal with on the border,” says Dr. Paul Ganster, the board’s chair and the director of the Institute for Regional Studies of the Californias at San Diego State University. The decade between 2001 and 2010 was the warmest on record in the Southwest, resulting in over a thousand heat-related deaths in Arizona alone. On June 19, 2016, temperatures in cities across Arizona set all-time record highs, including 118 degrees in Phoenix and 120 degrees in Yuma.

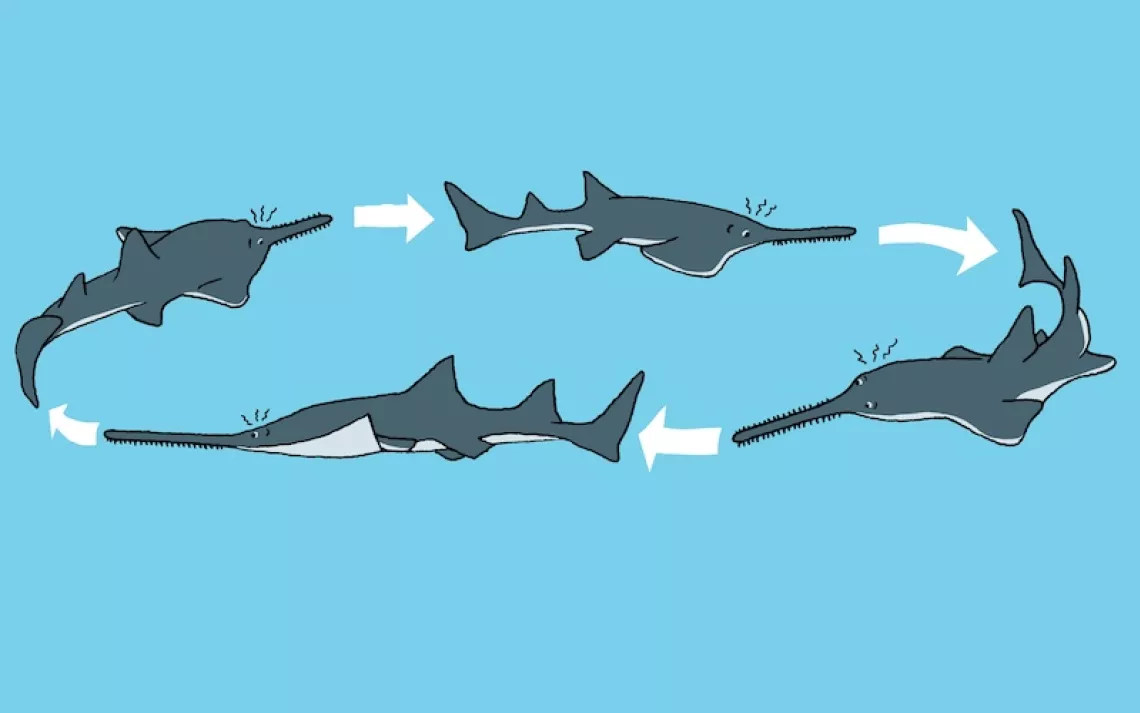

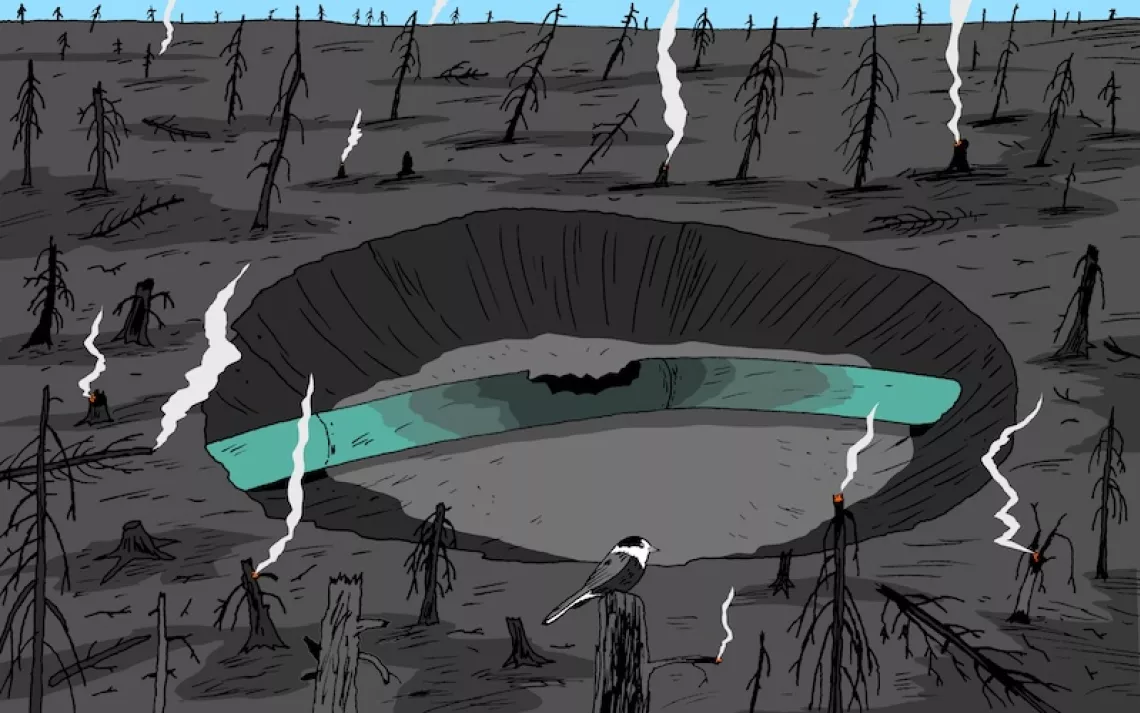

The effects of increasing temperatures, coupled with changing precipitation patterns, are widespread along the 1,900 miles that comprise the U.S.-Mexico border. Water scarcity is a growing problem in the Colorado and Rio Grande river systems, even as the population booms on both sides of the border. Ironically, the frequency of extreme precipitation events has also nearly doubled in places such as Texas’s Lower Rio Grande Valley. The resulting flooding is exacerbated by rapid development, which replaces absorbent soils with impermeable concrete. Many unincorporated Texas colonias were unscrupulously built up on known floodplains. Higher temperatures and floodwaters both contribute to the spread of the aedes aegypti mosquito responsible for passing on dengue fever, chikungunya, and Zika, the first locally transmitted cases of which were documented in Brownsville, Texas, in November.

Three of the 10 poorest counties in the United States are within 100 miles of the border, where overall a quarter of residents live at or below the poverty level, compounding the climate challenges facing the region. “Low-income populations tend to live in housing that is poorly insulated and without air conditioning in many cases, which makes that population much more vulnerable,” Ganster says. “Incidentally, substandard housing often doesn’t have screening, so they’re more susceptible to infection by the vectors.”

Low-income populations are also more likely to live near smog-belching ports of entry and highways clogged by the growth of NAFTA-era international trade. Such is the case of the Ysleta del Sur Pueblo tribe and sovereign nation, which is adjacent to the Zaragoza Port of Entry between El Paso and Ciudad Juárez. “It’s a moving parking lot, where you have so many cars parked during the entire day,” says Evaristo Cruz, the tribe’s environmental management director. “How do we address that? How do we get those vehicles to move a little faster and still be in sync with the demands of border security?”

Border climate challenges are particularly complex because many U.S. communities, like El Paso and the Ysleta del Sur Pueblo, adjoin larger cities on the Mexican side. “Political boundaries do very little, if anything, to stop environmental conditions,” Cruz says. “We need a regional, binational approach.” The report identifies case studies of successful cross-border collaboration, such as a “port of the future” under construction at the San Ysidro Land Port of Entry between Tijuana and San Diego. Scheduled for completion in 2019, the new port—which officials hope will be recognized with a highest-possible LEED Platinum designation—will dramatically reduce the wait times of idling vehicles while incorporating solar and geothermal energy and a rainwater harvesting system.

The board outlines over 30 recommendations that it says can be implemented relatively soon without significant increases in budget. Among these are a renewable energy program for tribal communities, an executive order on staffing levels during peak times at ports of entry, a binational mosquito surveillance and education effort, and streamlined outreach to rural and low-income communities that may lack the resources to access federal programs already underway in the border region.

Many of these recommendations, though, require more investment and binational cooperation at a time when President-elect Trump’s alarmist border talk overlaps with his climate change skepticism. “There’s a long history of cooperation between Mexico and the U.S. on a lot of these issues,” says Cyrus Reed, the conservation director for the Sierra Club’s Lone Star Chapter and a member of the Good Neighbor board. “Given the rhetoric of the campaign, it’s hard to think that there won’t at least be a time-out on some of that cooperation.”

Even without federal support, some recommendations might be taken up by local communities directly affected by climate change, Ganster says. “For example, recommendations regarding green infrastructure are quite appropriate for state and local governments as well as developers who want to create more sustainable communities,” he says.

Still, the question remains as to whether local efforts will work at cross-purposes with federal priorities. “Certainly, the vision of a wall along the border is not in keeping with this idea of green infrastructure,” Reed says. “There are several areas, such as in Nogales, where the fences that were built have led to huge storm water issues. With more extreme weather, you’re just exacerbating it with this brick-and-mortar-and-steel infrastructure. So, there are definitely challenges ahead.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club