The Sierra Club's 125-Year History Has Been a Story of Evolution

A writer and longtime Club member reflects on the organization's history

THE STORY OF THE SIERRA CLUB, taken in all at once, is astounding. The organization has expanded its membership, its perspective, and its reach so extensively that you could speak of several Sierra Clubs over the past 125 years. The current one would be unrecognizable not just to cofounder John Muir, but also to the subsequent white men who led it in the postwar era and battled over its future.

The Sierra Club has evolved with the country, just as it has evolved with the expanded understanding of natural systems and what it takes to ensure their integrity. The Club has led some of that understanding and its transformation into policy, and in that way has been unique in its impact. These colossal changes were not foreseeable; there were no great prophets, only people who responded well to surprises. What the past tells us about the future is that there will be more: surprises, evolutions, transformations.

When you take stock of what the Sierra Club has achieved over the last century and a quarter, remember that many of its greatest accomplishments look like nothing. They are not monuments to human achievement but the prevention of monuments to human folly. The monuments are calamities avoided: unbuilt ski resorts and coal-fired power plants; children who didn't get asthma and fish that didn't ingest mercury when that coal wasn't burned; nonexistent trash incinerators; forests that weren't logged and species that didn't go extinct; rivers that weren't dammed. The monuments are places where all the original species can continue their elaborate dances together as they did when we humans were a modest species with minor impact.

Perhaps the Sierra Club's greatest monument is how most of us, even far beyond the organization's 2.7 million members and supporters, imagine the world around us and what we value in it. During the last century, our consciousness in relationship to the natural world has changed more than most people comprehend, and the Sierra Club has played an essential role in those changes.

Evolutionary adaptability is a survival skill for organizations as much as it is for species, and the history of the Sierra Club is an example of evolution at work. The Sierra Club has metamorphosed to meet emerging changes in response to new ways of thinking and new constituencies and their perspectives, and in doing so has changed itself over and over. What will the Sierra Club be in 2042, on its 150th anniversary? In 2092, on its 200th? We can't foresee the future. When we study the past with care, we see that the future outstrips our imagination. The future will be shaped by people, groups, ideas, and movements that emerge unexpectedly from the margins and the shadows.

The arrival of the Trump team in the White House means that we're fighting to keep from regressing into the worst of the past, into ignorance of the elegantly interconnected natural systems on which we rely. This is the clear-cut bad news. The good news is less dramatic and more diffuse: There is an environmental movement well-equipped to resist Trump's retrograde agenda. And even beyond those who consider themselves a part of this movement, there is a pervasive love of the natural world and a willingness to protect it.

These are not givens, did not always exist, and did not inevitably appear. They are the results of an extraordinary, collaborative effort on the part of journalists, artists, scientists, organizers, and others to redefine Earth itself and our relationship and responsibility to it—and to point us toward the joys to be found in its places and processes.

This transformed consciousness, this love of the natural world, cannot easily be done away with. It is nothing less than a revolution in thought that has taken place over the last couple of centuries, intensifying over the past 60 years. It is the foundation on which we can continue to build. Or, to rewrite that thought with more wildness: This love of the natural world is the meadow in which we can continue to grow beautiful ideas and powerful movements. It is—make no mistake—a majority position.

SIERRA CLUB. IT'S A NAME so familiar that its bilingual eccentricities are seldom examined, but in the two words are two pieces of history butting up against each other. The word Sierra came from the south, from the Spaniards venturing into California from the colony of Mexico. Sierra Nevada is Spanish for "snowy mountains," first named thus and mapped in 1776 by Franciscan missionary and cartographer Pedro Font. (Native Californians had other names for the mountains.) The fact that half of the Club's name is Spanish—because it was founded in a place that was Mexico before it was the United States—was forgotten when anti-immigration activists tried to take over the Club in the late 1990s and early 2000s and use environmentalism as a screen for their agenda. But it says something about California—and the Club's geography. Until the 1950s, the Sierra Club was largely a California organization exploring and defending California places, especially the great range of granite peaks and lush valleys.

Club. That word came from the east. The small group of men who met in a lawyer's office in downtown San Francisco in 1892 intended to establish a mountaineering club like the Alpine Club of Britain, which sponsored expeditions among its genteel (and all-male, until 1974) members. Yet from its very beginning, the Sierra Club was different. The membership included women from its outset, and the organization had a broader mission than the other 19th-century mountaineering clubs. It was determined to be a political force. Here's the Club's original mission statement: "To explore, enjoy, and render accessible the mountain regions of the Pacific Coast; to publish authentic information concerning them; to enlist the support and cooperation of the people and the government in preserving the forests and other natural features of the Sierra Nevada."

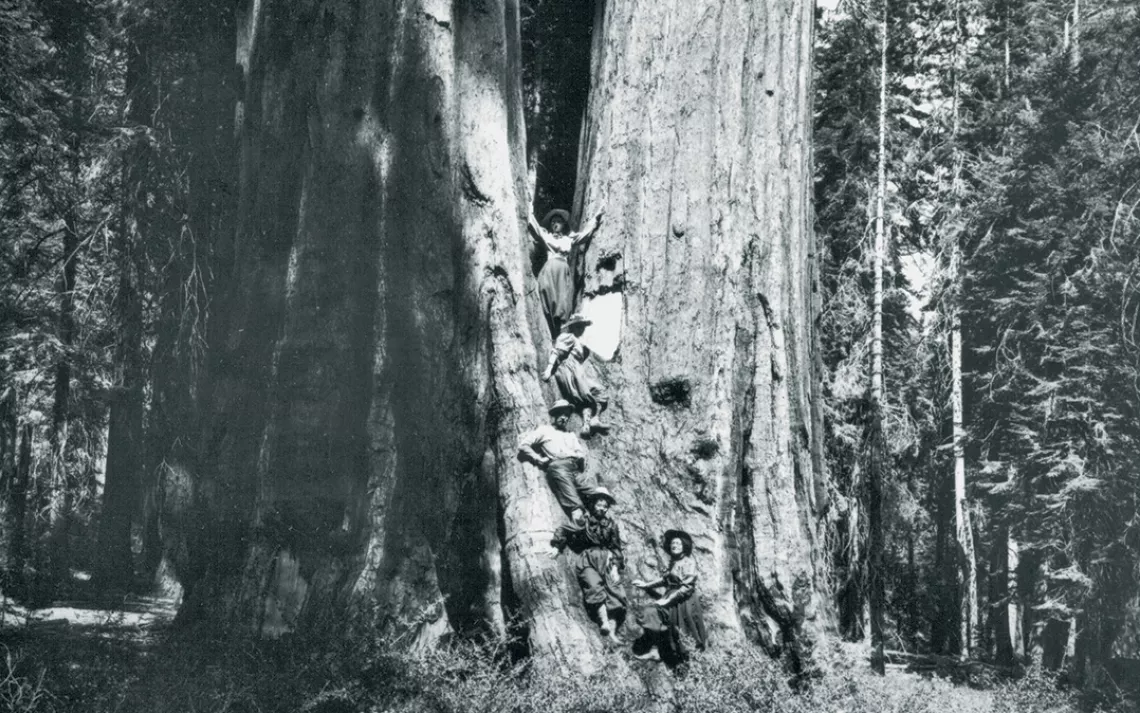

Though the organization did engage in political fights—most notably, the long, and ultimately doomed, campaign to prevent a dam in Yosemite National Park—it was for decades mostly an outdoors-adventure group. The Club organized outings—both big recreational excursions and more challenging mountaineering expeditions—and its early membership included many renowned climbers.

Clubbishness is sometimes a pejorative, and, as the Sierra Club expanded, some mourned the loss of close relationships among the members at large. In the 1950s and '60s, the Club broadened its bottom-up, grassroots, member-driven structure of local chapters, many of whose members know each other, work together to pursue local environmental goals, and campaign in local and national elections. No other environmental organization has anything quite like it, and it's created a model that can both respond to local land use and legislation and take on global problems and policy.

The midcentury witnessed years of crisis and creativity. The Club expanded in membership and mission, and in the course of doing so evolved from conservationist to environmentalist, from regional to national, and from mild to fierce. That is, the organization shifted from a focus on protecting particularly beautiful places to addressing whole systems: entire landscapes, energy generation, and chemical pollution. That was a revolution whose depth and breadth was staggering, and, since we now live inside it, hard to see.

John Muir famously wrote, "When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the universe." The full implications of that statement, however, were slow in arriving. And they came as revelations of horror as well as beauty. In the 1960s, fallout from nuclear weapons tests—mostly at the Nevada Test Site, just east of the Sierra Nevada—was showing up as strontium 90 in mothers' milk. In that decade, the Sierra Club began to worry about pesticides, too, when they were being sprayed with abandon in national parks, as well as on agricultural and residential land.

The Sierra Club's expansion of interests meant a shift from an ideal of separateness to one of inseparability, from setting places aside as parks and wilderness to recognizing that, due to air and water pollution and the atomic bomb, no place was out of reach from human impact. It meant acknowledging that how we live has everything to do with how ecosystems everywhere thrive. Or don't.

The transformation of the Sierra Club from a genteel regional conservation and outdoors group into a national environmental powerhouse was not smooth or easy. The board members struggled with whether it was more important to be reasonable and maintain good relationships with industry and government or to ratchet up their positions to meet changing circumstances and understandings. They argued and fought each other. Some quit. Some evolved.

These midcentury growing pains were an expression of a global revolution in recognizing that we cannot protect remote places without addressing what is in the air and the water everywhere; that "the environment" is not where some of us get to take our vacations, but where all of us live all the time. The change in thinking involved abandoning some of the cheerful faith in human intervention, in better living through chemistry and nuclear power (since we still don't know what to do with the waste that will remain dangerous somewhere for tens of thousands of years).

The 1960s revolution was about recognizing systemic interdependence. The consequences are still playing out. Some people continue to deny the interconnectedness that is ecological thinking, and even basic cause and effect, down to the impact of carbon emissions on the climate. Nevertheless, the new ecological awareness was, thanks to the Sierra Club and others, codified in law. By the early 1970s, the federal government had recognized the new world view with the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency, the Clean Air Act, and the Clean Water Act.

In the 1990s, the Sierra Club undertook another evolution as it began incorporating an understanding of racism and human rights into its environmentalism, a revolution that, like society's adoption of ecological thinking, is far from finished. My first work in the environmental movement took place at the end of the 1980s, when groups like Rainforest Action Network were confronting the reality that what white North American environmentalists had regarded as virgin wilderness was often, in the rainforest and the tropics, long-inhabited homeland. The same was true of other places, from the Arctic to the Everglades. This belated recognition led to the realization that human rights and environmental protection were not at odds or distinct but inseparable.

As white environmentalists acknowledged that almost every place had been inhabited, or at least known, by indigenous people before European contact, a revolution unfolded in how we imagined nature. The Wilderness Act of 1964 had set out to protect places "where man himself is a visitor who does not remain." I used to joke that the line had nothing to do with women, but it did suggest that humans did not belong in nature and that our only relationship to it was destructive. The story, more myth than actual history, erased millennia of indigenous presence. If that insight seems like something you always knew, you might be too young to remember how the old story was deconstructed and a new—or older—story came to take its place in textbooks, park signs, and land-management plans.

Though the idea of wilderness as a realm without humans had been a useful framework for protection, it often meant expelling native people from their ancestral lands, from Yosemite to Kenya. And it meant, sometimes, misunderstanding the ecology of a place and the role human beings had played in it. As I reported for Sierra in 1992, the Ahwahneechee of the Yosemite region used fire as a land-management tool. The open, parklike appearance of Yosemite Valley that had been seen as a miracle of nature was instead a result of the first inhabitants' skillfully set fires, which kept the forest from encroaching and helped the oaks whose acorns they harvested. A century of fire suppression turned many open meadows into overgrown thickets, prevented sequoias from regenerating, and fueled catastrophic wildfires.

I watched as the role of fire was accepted and controlled burns returned. It was a quiet revolution—and, like the others I have mentioned, is far from finished but well begun. As the official management of natural places changed, there came a revolution in how we thought about the human relationship to wild nature. Some cultures had never abandoned their vision of an integrated human-nature relationship. Recognizing this meant recognizing that human beings are not necessarily nature's enemy. We don't have to live in conflict with nature, or only cherish places in which we are absent or inert.

That evolved thinking, in turn, forced the Sierra Club to look closer to home, to places that were more polluted than pristine. This was the first step toward embracing the environmental justice movement, which addresses race and class as factors in who is likely to be dumped on or poisoned, to drink contaminated water or breathe dirty air. The new thinking took environmental activism beyond wilderness, and it meant building stronger alliances with communities of color. When I went to report on Hurricane Katrina's aftereffect in New Orleans, I met Darryl Malek-Wiley, a white southerner who'd been working closely with the mostly black community in the Lower Ninth Ward for decades. He'd been on the Sierra Club's staff since 1983 and was a trusted ally and collaborator in the African American community. If that seems unremarkable to you, then good; just remember that it would have been incomprehensible to many Sierra Club members in the 1950s.

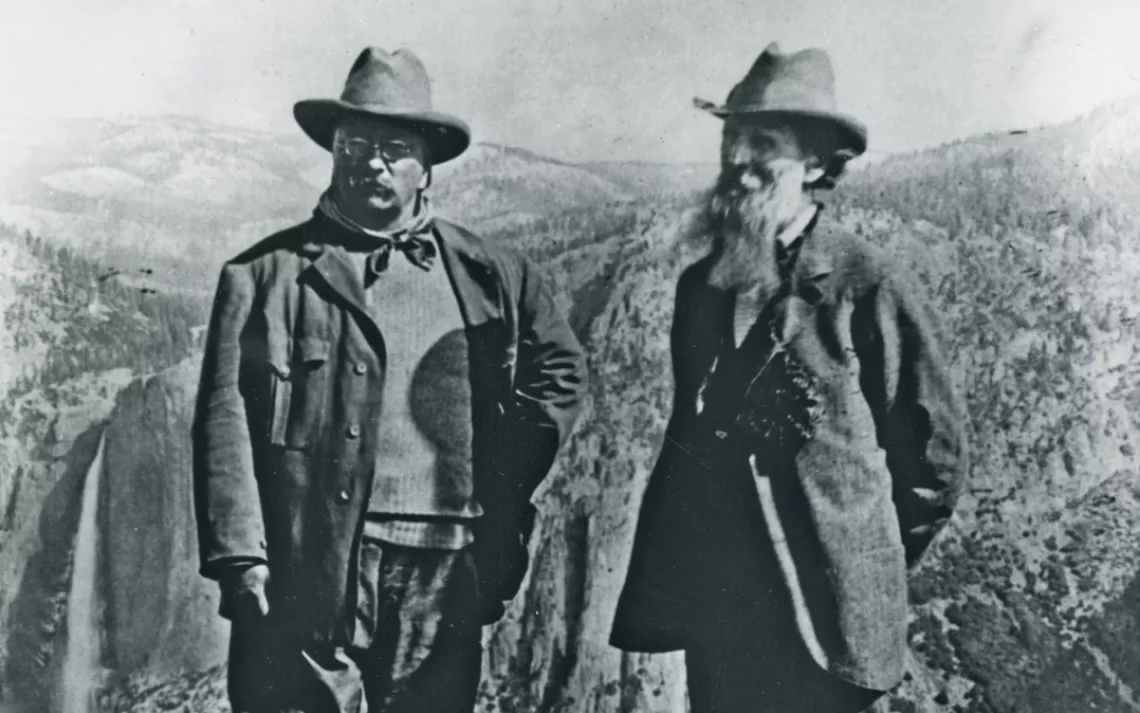

Sometimes progress happens so slowly and slyly that it's undetectable. Sometimes, though, it's unmistakable. Last year, the president of the Sierra Club and the president of the United States met in Yosemite. Two men holding those positions met once before, in 1903, when the Club's president was John Muir, the nation's president Teddy Roosevelt. And then 113 years later, it was Aaron Mair, the Club's first black president, with Barack Obama, the nation's first black president. Things change. The Sierra Club changed with them.

WE DON'T KNOW WHAT the future of the Sierra Club is because we don't know what the future of the nation or the planet is. We strive to play a role in making that future. But it seems likely that environmentalism will be ever more tightly woven into the fabric of everyday life, and everyone's lives, from indigenous people fighting against resource-extraction industries to the urbanites fighting for access to clean air and clean water. The history of the Sierra Club points to such a trajectory. We are heading toward a recognition of Earth as a magnificent orchestral system of infinite subsidiary systems, in which living beings and inorganic processes work together. To defend the resilience of those systems, their capacity to renew themselves and us, to understand that we can never again imagine ourselves as separate, and to understand that inseparability needs to be a social as well as an ecological vision—that's a beautiful arrival in the course of a long journey. It has been a journey toward interdependence.

This article appeared in the May/June 2017 edition with the headline "Declarations of Interdependence."

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club