The Atolls of Arkansas

Doomed by climate change, Marshall Islanders find a new home in Springdale

Some 15,000 Marshallese live in Springdale, Arkansas. Among them is JP Hemos. | Photos By Joseph Rushmore

IN THE LATE 1970S, JOHN MOODY, a native of the Marshall Islands, departed that double chain of coral atolls and flew eastward to Aeolonin Palle, the Atoll of White Men. His destination was the islet of Amedka, as distinguished from the islet of the Europeans, the islet of the Canadians, and the islets of the Australians and New Zealanders. He was bound for Middle Amedka and the University of Oklahoma on a Pell Grant. In 1986 or thereabouts, he moved to Springdale, Arkansas, married a local, and went to work at Tyson Foods.

And so the exodus began. Word of Arkansas spread as if by telepathy around the islands. Moody's journey from mid-Pacific lagoon and coconut palms to mid-continental mixed forest, cypress swamp, water moccasins, and Tyson would be prototypic of the emigration that followed.

Downtown Springdale, Arkansas

Today there are as many as 15,000 Marshallese in the Springdale area, plus more than 30 Marshallese churches, a Marshallese radio station, Marshallese convenience stores, and, on Spring Street, a consulate of the Republic of the Marshall Islands. The Marshallese have a joke name for Springdale, an allusion to the Tyson poultry empire that employs so many of them: "Baotail," they call the town—"Chickentail."

At the consulate last summer, Eldon Alik, the consul general, summarized for me what might be called his Greater Marshall Islands Theory: "Wherever there are Marshallese, that's the Marshall Islands." Since the turn of this millennium, in phase with sea rise, Marshallese immigration to the United States has risen sharply. Nowhere have more Marshallese settled than in northwest Arkansas. Nowhere on Earth are the Greater Marshalls greater.

THE ATOLLS OF THE original Marshall Islands, population 74,000, spread across 750,000 square miles of ocean, and their barrier reefs enclose 7,000 square miles of lagoon. Yet the islets and atolls rimming those lagoons seldom exceed eight feet in altitude and collectively amount to less than 70 square miles of land.

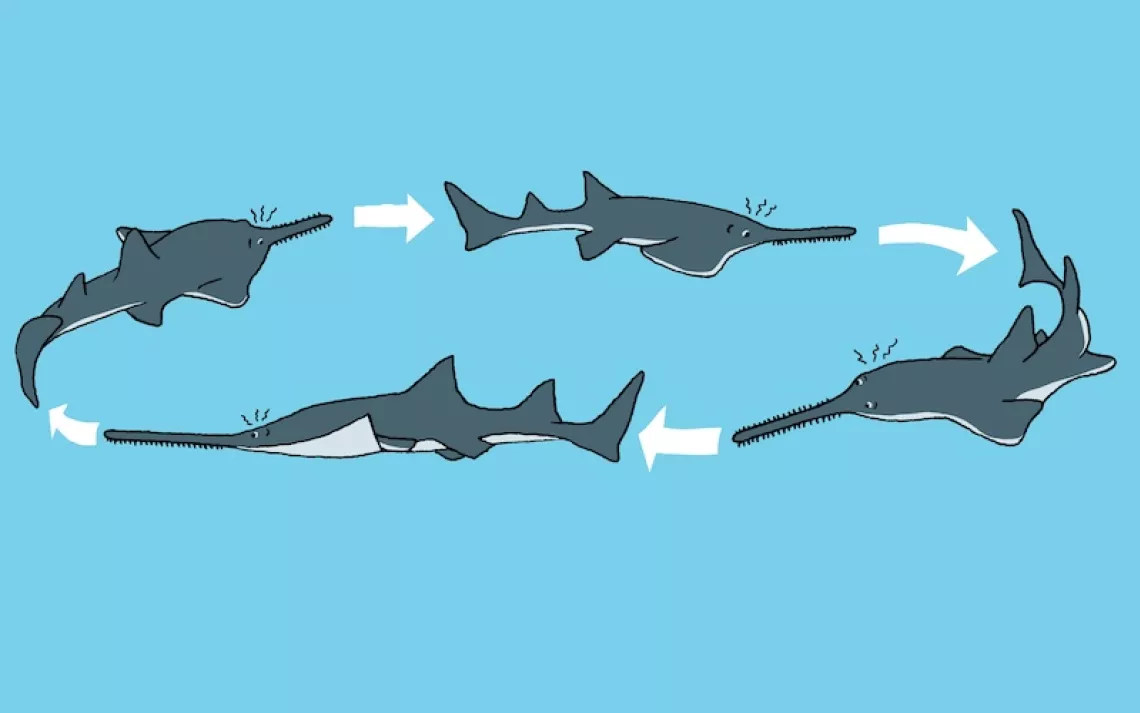

It fell to Charles Darwin, as usual, to figure out what coral atolls were. Sailing through the Maldives on the Beagle, puzzling over these rough circles and ellipses of turquoise in the royal blue of the Indian Ocean, he came up with an atoll-evolution hypothesis that turned out to be correct. Darwin's origin theory went like this:

With a roar of steam, a volcano breaks the ocean's surface, venting lava and sending up plumes of smoke and ash. This sudden mountain, a stratovolcano, builds skyward on alternating layers of lava and cinders. Its shoreline is colonized underwater by reef-building corals and then by mollusks, crustaceans, tunicates, sponges, and fish, all delivered by the current in nearly infinite variety. A coral reef, in all its profusion and complexity and incandescent color, encircles the mountain.

Jelly Laikidrik plays pool in the back of her parents' local business.

The volcano then subtracts itself from the equation, sinking of its own weight beneath the surface.

The barrier reef remains. In the tissues of the polyps of reef-building corals live symbiotic algae, which produce most of the corals' food. In order to photosynthesize, they must remain in the zone of brightness at the top of the ocean. As the volcano sinks, the coral colonies grow upward, chasing the sun. Wind and waves heap sand on the reef crest, eventually forming low islets. The reef becomes an atoll. Its islets are colonized by migrating and nesting seabirds, by seeds stuck to the feathers of those birds, by drift seeds, by bats, and by storm-blown insects and arachnids.

There was nothing especially original, then, in John Moody's trip to the Atoll of White Men. He was simply doing what atoll organisms do. He was the sticky seed in the feathers of the frigate bird. He was the green palm lizard arriving on its drift log. He was the windblown spider, ballooning in on its triangular parachute of silk.

Moody's journey was nothing new for human atoll dwellers either. For a hundred generations before him, his Marshallese forebears had set out for the horizon in outrigger canoes, fleeing war, typhoon, or famine, or just to see the world. Above them, luffing and filling on each new tack, was the spider's three-cornered parachute of silk, transfigured now—convergent evolution—into the isosceles triangle of the Oceanic lateen sail.

His impulse to move on was the same old one that settled the widest of oceans. Pushing off from some beach in Southeast Asia 7,500 years ago, the first tribes of Oceania ventured into the vastness of the Indo-Pacific, then the only large, habitable region of the planet as yet unexplored by humans. Opening before them was nearly half the surface of Earth. They committed themselves to that endless blue and the last great demographic adventure of our species.

NOW THE MARSHALLESE ARE on the move again, toward a continent this time, surfing in on the first wave of what will be a global tsunami of climate refugees. Their flight to Springdale demonstrates various truths about the new age we are entering: That the people least responsible for global warming and sea rise will suffer most from them. That climate change will generate backwash, a colonization of the colonizers. That for all the disruption, xenophobia, and ugliness ahead, there will be people of goodwill, both refugee and host, who try to make the best of it.

What the Marshallese demonstrate most clearly is that we are often victims of climate change before we know it.

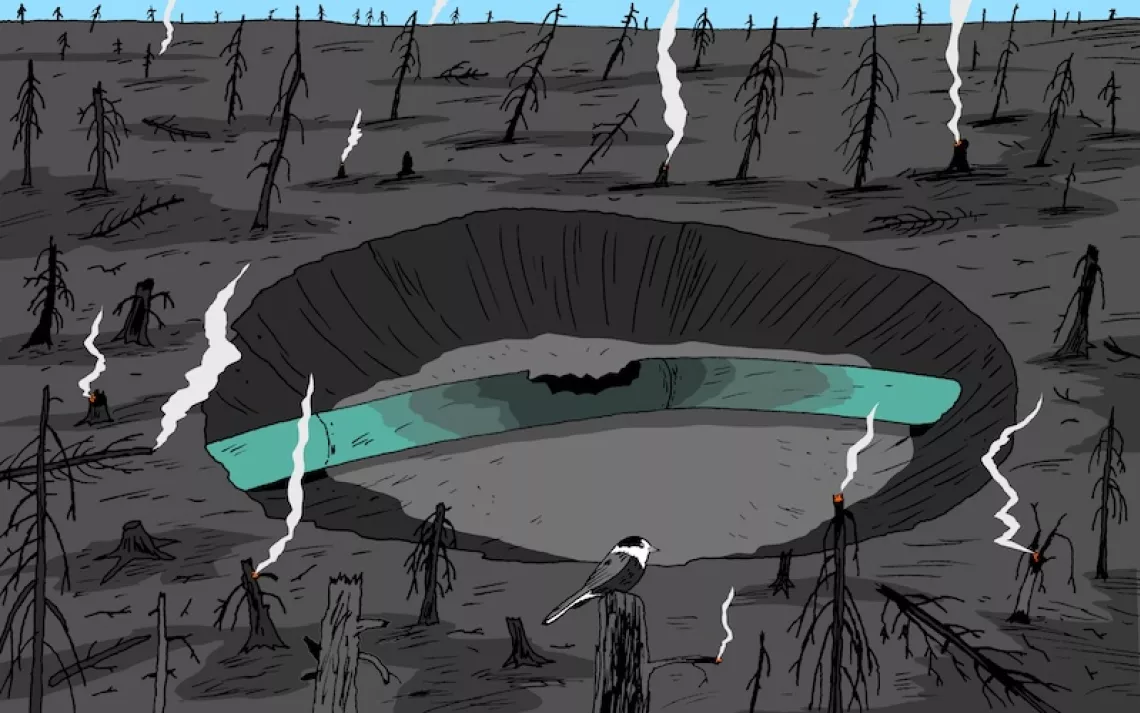

On the calm and sunny morning of November 26, 1979, a series of freak waves struck Majuro, the capital atoll. A subtropical high-pressure system named Alice had formed some days earlier in mid-ocean, 2,000 miles to the east, generating a 20-foot swell. When the first set of waves reached Majuro, oceanside residents were carried away in their houses and set down roughly elsewhere. The atoll's southeastern rim lay underwater for a day, drained nearly dry by evening, and then flooded again that night when a second set of waves arrived. Six days later, a third set of waves pummeled the atoll, along with gale-force winds.

Back then, nobody in the Marshalls was talking of sea rise. I know, because six months after Alice, even as John Moody departed, I arrived. Life on Majuro had returned halfway to normal, but evidence of the force of Alice's freak waves was everywhere. Whole rows of houses had been obliterated, leaving nothing but foundations behind. To shelter the dispossessed, neat military rows of blue Red Cross wall tents had sprung up on several islets.

It is impossible to say how much anthropogenic climate change contributed to Alice. But the inundation showed what happens when a few inches of elevated sea level coincides with high tides and big swells on a patch of ocean containing low-lying atolls. The blue tent cities of the dispossessed were a peek at the future.

THE MARSHALLESE SUFFER from some of the highest rates of diabetes known. Health assessments have found that 46.5 percent of Marshallese adults in Arkansas have diabetes and an additional 21.4 percent have prediabetes. They tend to view the disease as a curse on their race—an inevitability, not a preventable or manageable disease.

Dr. Sheldon Riklon spends much of his time treating diabetes, which nearly half of the Marshallese in Arkansas suffer from.

Dr. Sheldon Riklon, one of two Marshall Islanders to become an MD, is an associate professor at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences in Fayetteville, 10 miles south of Springdale. He spends half his time at the university doing health research on diabetes in the Marshallese community, the other half as a primary care physician at the community clinic in Springdale. When I met him last June, he was in Fayetteville in his research mode.

"When we asked the Marshallese community here what exactly are your concerns, diabetes was the top thing," he told me. "We've started different diabetes projects. One is the Diabetes Self-Management Education program. It's focused on the family more than the individual. That's good, because Marshallese are focused that way too. The other project is the Diabetes Prevention Program; it comes out of the CDC. The original version, we know it works for the folks down in the [Mississippi] Delta, but that's more about the African Americans. Something similar was done in Hawaii for the Native Hawaiians. So we kind of meshed the two and made it into more of a Marshallese version."

That the Marshallese should need such programs is ironic, given the good balance of the traditional Marshallese diet: fish, taro, cassava, breadfruit, the occasional pig. "You know our traditional Marshallese diet was the healthiest diet!" Riklon told me. "We were really healthy, robust people. We were not sick like we are now. We were not obese. We had muscles, brown skin; we were working the taro garden, going fishing every day, bringing down the breadfruit. That was our traditional way of life."

The Marshallese community gathers for a funeral in Springdale.

Traditionally, the fish and breadfruit of the Marshalls were not radioactive. Then, between 1946 and 1958, the United States detonated 67 nuclear and thermonuclear bombs in the northwestern atolls of the Marshalls, a total yield of 108,496 kilotons, or more than 7,000 times the force of Little Boy, the A-bomb that destroyed Hiroshima. The Castle Bravo H-bomb test, on Bikini Atoll in 1954, was one of several "runaway" tests in the Marshalls. The physicists omitted an important fusion reaction in their calculations, causing them to gravely underestimate the yield; they expected a bang equivalent to 5 million tons of TNT and got 15 million tons instead. The wind changed direction just before detonation, putting the Marshallese atolls of Rongelap, Rongerik, and Utirik in the path of the radioactive cloud and its fallout. Most of the inhabitants lost their thyroid glands to surgeons; explosions of cancer and what the Marshallese call "jellyfish babies" followed.

"Diabetes, you try to relate that to the nuclear-weapons testing program—that's hard," Riklon told me. "But look. You destroyed our land. You destroyed where we go and get our fish, where we grow our taro and vegetables. You changed our way of living. We're not fishing in the morning. Instead we're eating canned goods sent by the USDA—canned chicken, canned fruits and vegetables, Spam. 'Eat these, because they're safer for you. They're not irradiated.' We all know now that those are unhealthy. And of course, you can't go out early in the morning and grow Spam. You can't grow canned chicken. You're going to just sit around."

Dr. Pearl McElfish is head of the Office of Community Health and Research at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Northwest and co-director of the Center for Pacific Islander Health. She pointed out that now "the canned stuff becomes seen as traditional food. Rice and Spam are now seen as cultural Marshallese foods."

McElfish, like Riklon, is agnostic about possible transgenerational health effects from nuclear testing. "The Marshallese ask me this all the time," she said. "My response is that it's certainly possible, but we don't know. What we do know is that it's created a level of fatalism, a belief that everything is tied to nuclear testing. 'Yes, I have diabetes, but it's because of the radiation.' Which means there's less understanding that outcomes can be changed."

McElfish studies health disparities in northwest Arkansas. The worst, she said, are experienced by the Marshallese and first-generation Mexican immigrants. There's been good progress in addressing them, "but there are many deep problems that are not going to be solved in a year or two. The primary thing is restoration of Medicaid. Until we have that, everything else I do is a drop in the bucket."

Marshallese immigrants once had access to Medicaid and other federally funded benefit programs thanks to the Marshalls' Compact of Free Association with the United States. Then came welfare reform—the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996—which excluded them from Medicaid and the Children's Health Insurance Program. McElfish doesn't believe that the exclusion of the Marshallese from Medicaid was strategic. It's more that they are a small population, are not vocal, are denied the vote, and have simply fallen through the cracks.

McElfish's fondness for her Marshallese patients, her depth of engagement with their problems, and her hard, clear thinking about how to smooth their transition to life in the American South are characteristic of Marshall Islanders' reception in Arkansas—a welcome they have not always encountered elsewhere in the United States. It is not by accident that 15,000 Marshallese have been drawn to Springdale.

THE MARSHALLESE DIFFER in one important respect from many of the other climate refugees who will soon be on the move. Where others will seek cooler temperatures or move inland or uphill to escape sea level rise, the Marshallese have no inland and no uphill. Eventually, the Republic of the Marshall Islands, like the atoll nations of the Maldives, Kiribati, and Tuvalu, is slated to disappear from the planet.

In all my talks with the Marshallese of Arkansas, only one person voluntarily mentioned this prospect. I had to prod: What happens to the Marshallese when there is no longer a Marshall Islands?

"Even if the Marshall Islands are going to be gone, even if they're inundated and underwater, I think we'll still be Marshallese," Riklon said. "Because we still have our culture that we're going to cling to. As long as we have our language and our culture."

Perhaps. But what become of a language and a culture when their referents are gone? In Marshallese, for example, there is a profusion of terms for reef-fishing techniques. Obbar means "to poison fish with the fruit of the wop tree." Juunbon is "pole fishing on the barrier reef edge at low tide on dark nights." Kiijbaal is "hanging on to reef while spearing." None of these techniques, or any of the hundreds of others in the vast repertoire of Marshallese fishers, is applicable to the bass and catfish of Arkansas.

Coconut terms proliferate in Marshallese. There is one word for the northern hemisphere of a coconut shell and another for the southern. There is one word for a coconut shell when it is used for catching coconut sap and another when it is used for scrubbing clothes. Ejej is the husking of coconuts by the claws of coconut crabs or by the teeth of human beings. Ninikoko is when two or more people share one coconut. Then there are the coconut metaphors (a coconut, it turns out, can be compared to almost anything). Ub means "unripe coconut" and "tender skin of a baby." Lat means "coconut shell" and "skull." Mir describes the red of reddish coconuts and also the red of dawn and dusk.

Coconut palms are scarce among the loblolly pines, oaks, and hickory trees of Arkansas.

On a coral atoll, it's impossible to escape the sound of the ocean. The word bunraak means both "breaking of waves" and "falling of words from the lips." Mool means both "an interval of smooth surf after a succession of rollers" and "a free moment." Llao means both "disgusted" and "seasick."

There is no ocean in Arkansas. Words in Arkansas do not fall like breaking waves from the lips. What happens to words, to their inner light, when they are cut off from their roots? The very first person I met upon arriving in Arkansas was a small, efficient Marshallese woman named Justina, who was using a microphone to organize passengers for their walk down the gangway. We chatted, and I mentioned that I had brought my old Marshallese-English dictionary with me. She got very excited and asked if I had an extra one, because she was having trouble explaining to her sons the meaning of many Marshallese words. Their exact sense was slipping away from her.

MELISA LAELAN is the president of the Arkansas Coalition of Marshallese (ACOM), a nonprofit she cofounded in 2011. She and six staff members work out of an office decorated with leis, fans made of plaited palm fronds, and a model of a Marshallese outrigger canoe. Laelan is a niece of the chief who owns much of Majuro, and the Arkansas press has referred to her as a princess, which seems to embarrass her. She was quick to point out that she is a working mother and that whatever she has achieved, she earned. Laelan left the Marshalls at 17, joined the U.S. Army at 18, and served 10 years in South Korea, Germany, and the Balkans. "I loved it," she said.

Laelan credits army discipline and her training in supply and logistics and, later, the law as preparation for the work she does now at ACOM, serving as a bridge between the Marshallese and non-Marshallese communities of Arkansas. When there are misunderstandings and friction, she and her staff explain Marshallese culture to Arkansans, and vice versa. ACOM helps islanders with their passports and I-94 forms and runs a driver-education course (Marshallese drivers on the islands don't need a license) and a savings program through which the Marshallese can build college funds for their kids.

I asked my question: What happens when the Marshalls are gone?

"In some ways, we'll lose our governance," Laelan said. "We really won't have a foundation. It's going to be a big loss."

She glanced out the window at blue sky and the last puffy clouds of Arkansas spring. It was the first day of summer. She laughed sharply. "Here I'm saying this, yet I'm always someone who believes in moving on. 'Work with what you have now!' That's what I tell myself. 'You're already here in the U.S., in Arkansas; you have an office; you built ACOM. Use that and move on. Use it to the max to serve your people.'

"So I still believe this, but I also have to say, if the islands are gone, we will lose everything."

CARMEN CHONG GUM, the first Marshallese consul general in Arkansas, met me at the Springdale Library on Pleasant Street. It was an old habit for the former diplomat, as she used to conduct business there in her early days. "At first, I was running the consulate from my car, our family vehicle. I was officeless. If people wanted to meet with me, I would do it at their place or at the library."

Chong Gum spoke slowly, reflectively, almost dreamily, comfortable with pauses. I never had to ask my painful question, as Chong Gum went there herself.

"I grew up with tidal waves on Majuro," she said. "I think it was three tidal waves that I saw. At that time, as a little girl, I wasn't scared. But now, being away from the islands for so many years and then going back, you see the difference. You see the erosion. You see the shoreline is coming in. Growing up, you don't see it. There was one trip, flying over and looking down, I got that chill. Suddenly I was overwhelmed with fear. For the islands and the families. The islands look so tiny and vulnerable, fragile. Just looking down, I was like, 'Oh my God, what if one big wave comes?' "

This article appeared in the January/February 2019 edition with the headline "The Atolls of Arkansas."

This article was funded by the Sierra Club's Beyond Coal campaign (beyondcoal.org).

For generations, a Chevron oil refinery has dominated the industrial town of Richmond, California. Doria Robinson of Urban Tilth has a plan to reinvent her community. Read about it here.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club