Zen and the Art of Carbon Ideology

William T. Vollmann travels the globe investigating climate change

What would it be like to investigate the science of climate change for yourself? To sort through tables and graphs, crunching the numbers? To travel the world searching for evidence? What would it feel like to realize, after all the research is completed, that you are part of the problem?

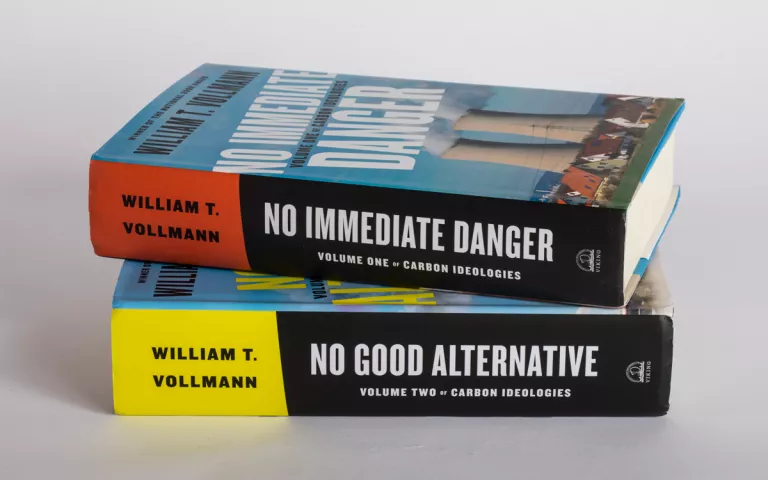

Chances are, the result would look something like William T. Vollmann's two-volume climate opus, Carbon Ideologies (Viking, 2018), which is equal parts gonzo journalism, hand-wringing confessional, and one hot mess. The books—written in the form of a letter to a future reader who, presumably, is on the wrong side of the history we are in the process of creating—document Vollmann's quest to understand how capitalism, consumerism, and fossil fuels are ruining the planet.

Vollmann is a National Book Award winner known for immersing himself in his subject matter. In No Immediate Danger, volume 1 of Carbon Ideologies, he takes this to a new level. Vollmann travels from the Mexican city of Poza Rica to Oklahoma City to Dubai, interviewing scientists and coal miners, environmental activists and waitresses. He constructs diagrams of everything from the carbon produced to make adipic acid for nylon pantyhose to the amount of power required by an electric toothbrush. He packs these findings into 600 pages, along with photos and listicles that sometimes burst from the page in big, bold fonts. The book ends with Vollmann focusing on nuclear energy. He journeys to Fukushima to interview tsunami survivors, taxi drivers, and power plant representatives, concluding that the deadly consequences of nuclear power are irrefutable.

"What was the work for?" Vollmann repeatedly asks as he muses about the human labor that produced those pantyhose and that electric toothbrush. The answer, to him, is glaringly obvious: We are all carbon ideologues. "Ideologues of good faith advanced their respective agendas by way of the free market," he writes. "We all bought what they sold."

In volume 2, No Good Alternative, Vollmann turns his attention to coal, oil, and natural gas. He delivers a withering account of how well-meaning working-class families have accepted coal as a patriotic duty. On the road from Appalachia to New Mexico and Colorado to Bangladesh, Vollmann tracks the fossil fuel culture embedded in fast-food restaurants and churches. "What do you think about global warming?" he asks anyone who crosses his path. "Maybe God takes care of that, with plagues and so forth," a retired oil magnate replies. In Bangladesh, he asks a labor union president what he thinks of the "coal situation" there. The man's answer lands like a death sentence: "There's no alternative."

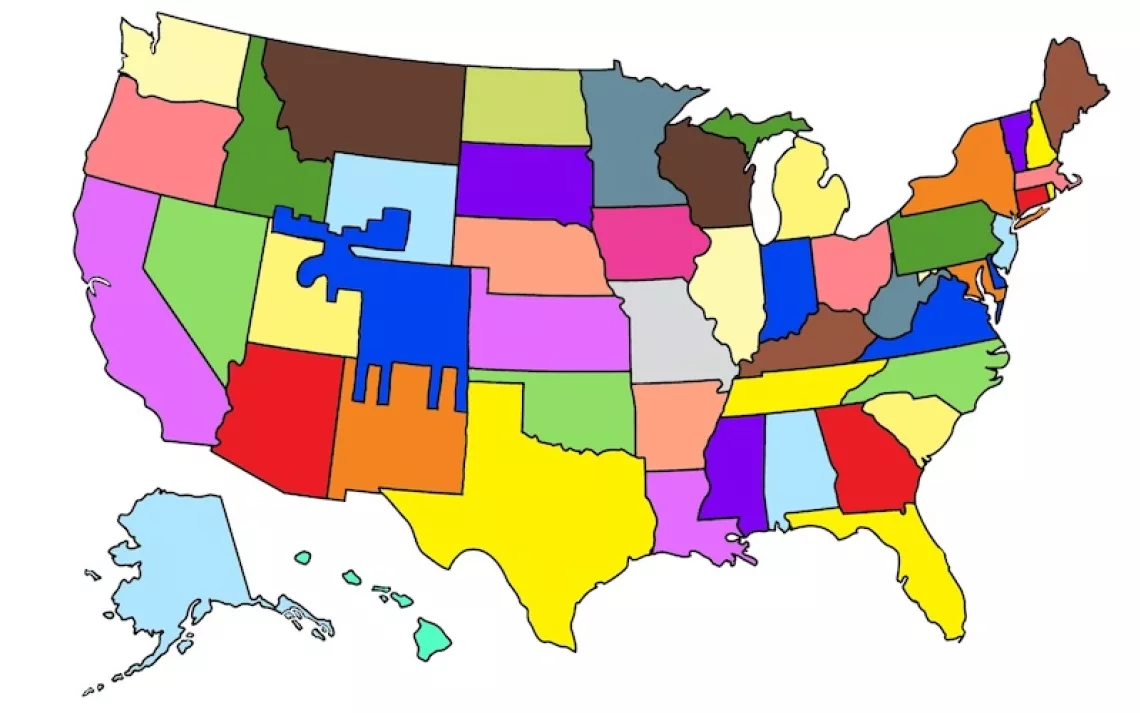

What of those who accept the scientific consensus regarding human-driven climate change? Those who compost and recycle, who try to do their part? Even these well-intentioned actions often take place after we've already spent the day boiling water for coffee or tea, driving to work, charging our phones, and machine-washing clothes (drying them uses 4 percent of the total energy consumed in U.S. homes). The list of all the environmental harms we cause in the process of just living our lives, much of which has a carbon price attached, is endless. We must scrutinize these day-to-day practices and routines—not just the activities of ExxonMobil and TEPCO, Scott Pruitt and Don Blankenship—if we are to save Earth's natural abundance before it's too late.

"We destroyed ourselves," Vollmann writes, "not simply because we burned too much steam coal or heavy commercial fuel oil in our power plants, but also because we followed sound agricultural practices, and because we made useful and beautiful things of all sorts."

This article appeared in the September/October 2018 edition with the headline "To Love, With Dystopia."

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club