Climate and COVID: A Lethal Combination for the World’s Poor

That’s one big takeaway from a recent report by CARE International

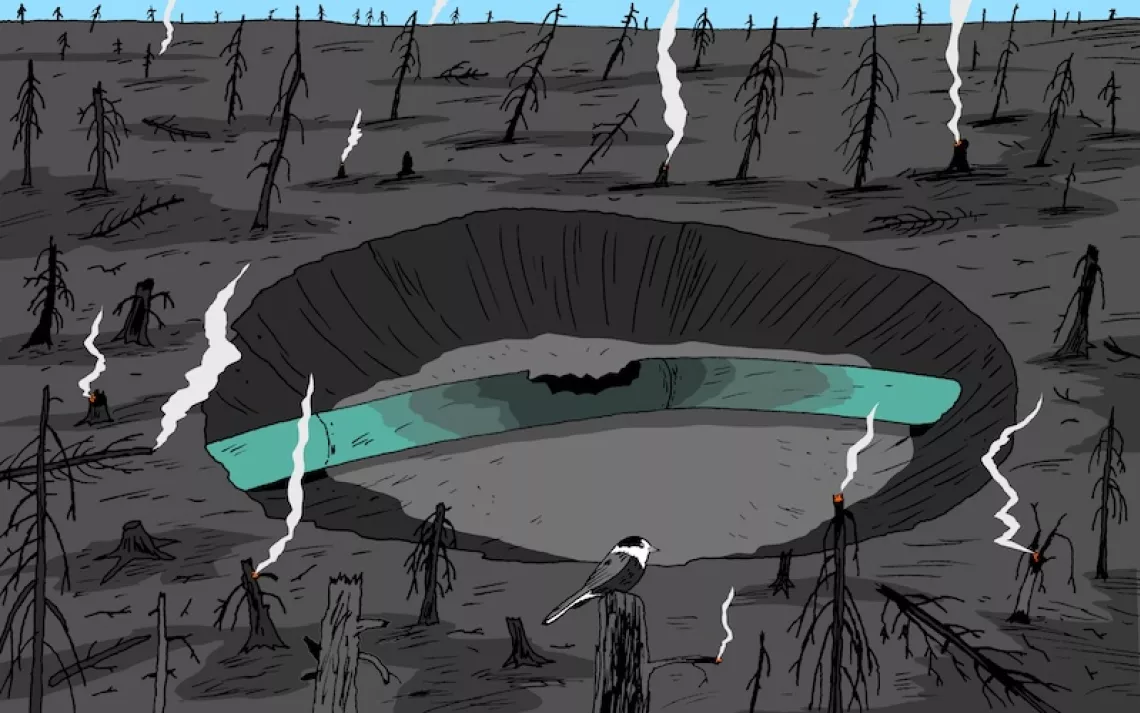

A village hit by wildfires in eastern Ukraine last fall. | Photo by AP/Ukrainian Presidential Press Office

In 2020, the world’s top 10 humanitarian crises together received less media attention than Kanye West’s bid for the presidency and the launch of the PlayStation 5. That’s according to The 10 Most Under-Reported Humanitarian Crises of 2020, a report released in January by the aid organization CARE International. The most overlooked humanitarian crisis, unfolding in Burundi, received a mere 429 media hits last year.

CARE’s fifth annual report, which is based on an analysis of online news coverage in five languages, shines a light on broad gaps in international reporting and should make journalists everywhere cringe, but it contains other important takeaways as well. A look through the summaries of each country in crisis reveals an unmistakable theme: Climate change and COVID-19 are a lethal combination for the world’s poor.

In 2020, floods, droughts, cyclones, and wildfires pummeled countries whose economies were already reeling from the devastating pandemic, driving millions deeper into poverty and worsening food insecurity. Around the world, the two crises have increased the number of people in need of humanitarian assistance by 40 percent—the single largest increase ever recorded in one year.

For example, in Zambia (number 10 on CARE’s list), the economy contracted by about 4.5 percent after the pandemic disrupted world commodity markets and pushed down the price of copper, a major export. At the same time, the country experienced such severe and prolonged drought that the government banned exports of grain. More than half the population needs humanitarian assistance.

Add political conflict to the mix and it’s a trifecta of disaster. The Central African Republic, third on CARE’s list, has been in the grip of a brutal civil war since 2012. One in four Central Africans is displaced either within the country or in neighboring ones. “These displacements,” says the report, “combined with poor rains during planting season, and along with invasions of fall armyworms and locusts, have put 1.93 million people at risk of starvation.” On top of this, COVID-19 containment measures and border controls have made it difficult to supply markets, driving up the price of basic foods like rice, oil, and sugar.

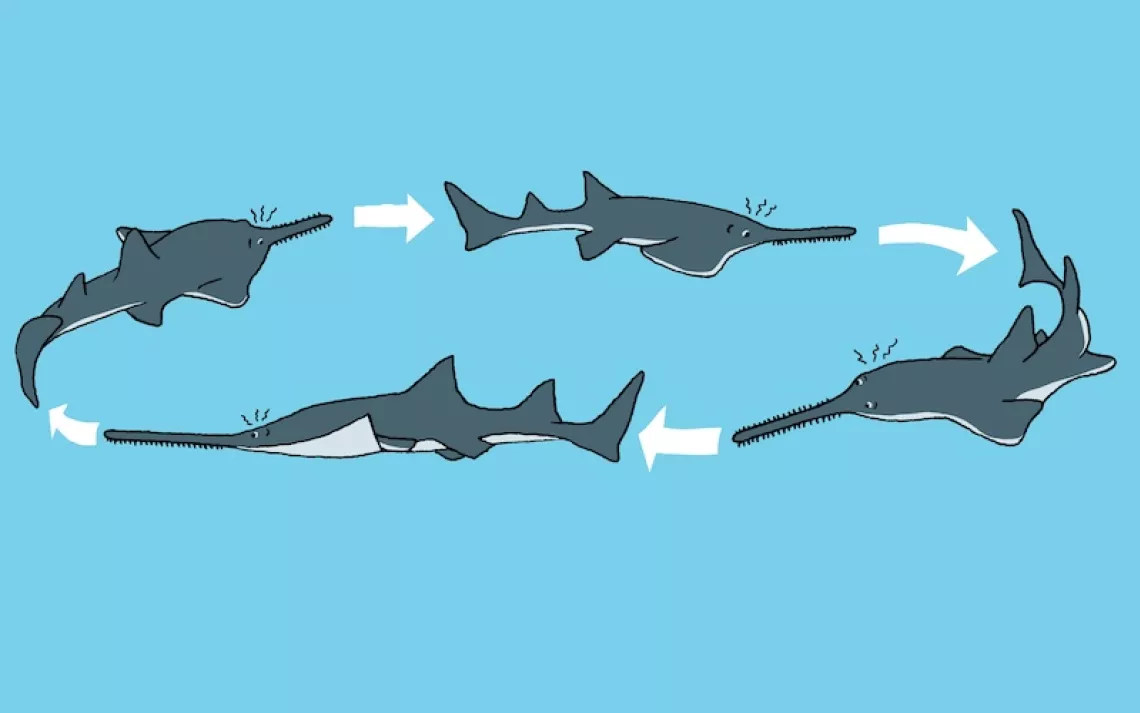

Climate change, COVID-19, and conflict are also contributing to a humanitarian crisis in the eastern part of Ukraine along the 260-mile-long contact line dividing the government-controlled area from areas run by separatists. Those who can have fled—30 percent of the people living in the conflict zone are elderly or disabled, which means they are especially vulnerable to the virus. In September, a wildfire tore through the area, burning down 500 homes.

Guatemala (second on the list) has been plagued by protracted drought and sporadic bouts of torrential rain since 2015, leading to continual crop failures. Before the coronavirus, the country had the sixth-highest rate of malnutrition in the world. With the onset of the pandemic, households have lost their income as a result of business closures, and remittances—money sent from family members working abroad—have decreased significantly.

“With each crisis, you see a continuously deteriorating situation,” Sven Harmeling, CARE’s climate change and resilience global policy lead, says about the countries highlighted in the report. “It’s just a very dangerous mix of things.”

As for why these dire situations garner so little international media attention, Harmeling, who is based in Germany, thinks one reason is that developed countries, which play an outsize role in global media markets, have been busy dealing with their own domestic problems amid the pandemic. When he does see reporting about extreme weather events in other countries, it tends to focus on grim new records like the quantity of rainfall or wind speed. But, he points out, there are many mid-level events that cause newsworthy destruction.

Lemekeza Mokiwa, a Malawian with CARE International who specializes in food, nutrition, and climate resilience, says the situation in his country is similar to that of others described in the report. When the pandemic began in March, Malawi (sixth on the list) still had not fully recovered from Hurricane Idai, which had struck the year before, flooding wide swaths of farmland right before harvest season. “COVID-19 has just added salt to the wound,” he says. Like elsewhere, restrictions put in place in response to the pandemic have led to the loss of jobs and remittances from South Africa.

Seven out of 10 people live below the poverty line in Malawi, one of Africa’s most densely populated countries, and the economy is heavily reliant on rain-fed agriculture. “We experience a lot of flooding, drought, hail storms, strong winds, and sometimes landslides. All these natural disasters, including also the pest outbreaks, are contributing to the poverty in Malawi,” Mokiwa says. Malnutrition and diseases like cholera and malaria are on the rise.

Mokiwa says the ongoing crises also exacerbate existing gender inequities. “Whenever there’s a disaster and people are in the camps, women are exploited so they can receive some relief items.”

It’s easy to read The 10 Most Under-Reported Humanitarian Crises of 2020 and despair at the depth and breadth of human suffering documented in its pages, but the biggest takeaway is not hopelessness. Media coverage that draws connections between each country’s complex and overlapping problems—and that advances solutions—is sorely needed. Harmeling finds some hope in the fact that solutions exist to help tackle both COVID-19 and climate change—for example, equipping health systems in rural areas with early warning systems and solar panels to make them more resilient in the face of disasters and able to cool vaccines.

“We need to be honest about the depths of the crisis we’re facing,” Harmeling says, “but it’s also important to show that there are solutions that can be promoted, repeated, and scaled up. Often these solutions work because of committed individuals who by their leadership bring their communities together in a time of crisis. That’s a very important part of the story.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club