As Florida Citrus Loses Its Sweet Taste, Scientists Are on the Hunt for Solutions

A citrus disease has led to a decline in sweetness and taste. Can scientists find ways to keep the industry afloat?

Florida, once famous for its orange juice industry, is struggling to maintain the crop's signature taste as citrus greening disease continues to plague groves across the state. | Photo courtesy of UF/IFAS

When Florida’s commissioner of agriculture, Wilton Simpson, took the stage at the annual Citrus Expo in Tampa, Florida, last month, the room full of farmers expected answers. When the floor opened to questions, one concerned attendee asked the question on everyone’s mind: “How can we get Florida back to its former glory of orange juice?”

It wasn’t news to anyone in the room that Florida, once famous for its citrus industry, is now struggling to produce enough high-quality fruit to fill grocery stores with its signature orange juice. And it’s not just oranges: grapefruits, tangerines, and lemons are also struggling. The problem is a plant disease known as “citrus greening” that Florida growers have been struggling with for two decades. “It’s not from lack of energy to want to solve the problem,” the commissioner explained. “The challenge that we have there is it takes so long to determine whether it actually works or not.”

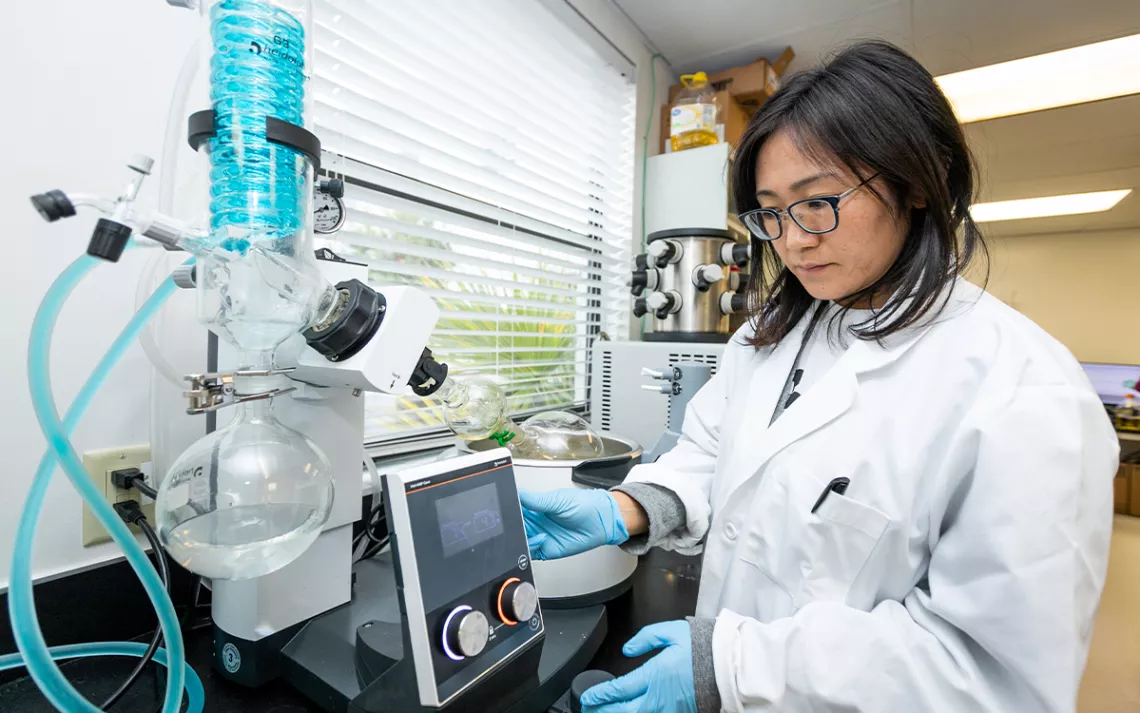

Flavor chemist Yu Wang and other University of Florida scientists are researching ways to use natural chemical compounds in citrus fruits to sweeten orange juice affected by citrus greening. | Photo courtesy of UF/IFAS

Simpson was referring to an array of research strategies focused on curbing the disease: gene-editing tools like CRISPR; new orange varieties that are more disease-tolerant; and, perhaps most promising, commercial antibiotic trunk injections for sick trees. It takes three to five years to test any of these techniques, scientists warned at the Citrus Expo, because it takes time for citrus trees to grow in the lab before employing them in farmers’ groves under real-world conditions. The quest for solutions has been a marathon; no quick fixes are in sight.

Citrus greening, also known by its Chinese name, Huanglongbing (or HLB), has plagued Florida’s citrus groves since 1998. Now, more than two decades later, it continues to bedevil the state’s exasperated growers—as well as the scientists who are researching cures. Last year, the effects of Hurricane Ian made matters even worse. The state’s $6.8 billion citrus industry ended the 2022–2023 season with just 16 million boxes of oranges, according to the USDA—one of the lowest yields since the Great Depression. In comparison, the state produced close to 250 million boxes in 2004, before orange groves started showing signs of citrus greening. That’s nearly a 94 percent decrease in production in just 20 years for an industry that used to be king.

Lower fruit yields are a major concern for growers and juice processors alike. Citrus greening also involves a less-discussed but equally serious effect: It makes the fruit juice taste funky. That’s because citrus greening lowers sugar levels and alters the chemical compounds in the fruit. And there are other causes of altered taste too. Extreme temperatures and weather events such as hurricanes and winter freezes place added stress on citrus trees, spurring chemical changes that cause bitterness. “If we lose the taste, why not just pop a couple vitamin Cs?” said Scott Farr, a citrus grower in Wauchula, Florida, during the expo.

Citrus greening is caused by the Asian citrus psyllid, a tiny invasive bug that infects trees by spitting bacteria into the leaves. The trees recognize the bacteria just like our bodies would recognize a virus: Their immune defenses kick in. To stop the infection from spreading, the tree produces a chemical that clogs the phloem, the blood vessels of the tree that transport nutrients through the inner layers of the bark.

Asian citrus psyllids, the tiny bugs that transmit citrus greening disease, produce white, waxy bulbs that look like shavings. | Photo courtesy of UF/IFAS

“But on the downside, what happens is that now, when a leaf photosynthesizes—when it produces its food and sugar—it’s not able to move that sugar within the tree because the highway is jammed with traffic,” explained Tripti Vashisth, a citrus horticulturist at the University of Florida. As a result, fruits are often stunted, don’t grow at all, or drop off the tree prematurely. This puts the tree under stress. “And whenever that happens, it produces certain compounds which give it more of (an) astringent flavor and a bitter flavor,” Vashisth said.

As a result of the infection, the average level of soluble solids in citrus fruit, known in the industry as Brix, has steadily dropped over the years—and that correlates with a decline in sweetness. Brix levels decreased by 20 percent in just one decade, according to data from the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services. Meanwhile, the 2021 season’s levels sat at just 10 degrees Brix, lower than the Food and Drug Administration’s 10.5-degree requirement for pasteurized orange juice. In response to the collapsing sugar levels, two citrus industry groups recently filed a petition requesting that the FDA lower its Brix requirement; the proposal is now accepting public comment until October 16.

Citrus greening has become so pervasive in Florida orange groves that the state’s juice processors have been forced to import Brazilian oranges, which are sweeter, to mix with Florida’s crop so the juice meets the FDA’s Brix standards. Now, in an effort to find another solution, flavor chemists are investigating how natural chemical compounds can produce a sweeter, tastier juice.

“A major part of our work is to improve the citrus flavor quality of the fresh fruit and the juice,” said Yu Wang, a citrus flavor chemist at the University of Florida Citrus Research and Education Center. Last year, Wang and her colleagues identified for the first time seven natural sweetening compounds in citrus by fishing them out of different fruit varieties. Their findings included one compound called oxime V—an artificial sweetener that has never been found in nature before—and it’s 400 times sweeter than sugar. Together, the compounds are known as flavor modulators, which interact with receptors on our tongue to alter how we taste certain food molecules. Prior to Wang’s study, only one sweetness modulator was known to exist in citrus fruits.

Here’s how flavor modulators work: Our somatosensory systems detect a combination of flavors at once as we savor our food. Think of the film Ratatouille when Remy, the rat chef, takes a bite of cheese, then a bite of fruit, and then experiences a flavor explosion when he tries both at the same time. There’s a science behind that known as flavoromics, which is analyzing the whole gamut of sensory components that contribute to our perception of smell and taste using chemical fingerprinting. “When you're perceiving something like orange juice, you're not perceiving a molecule that tastes like oranges,” said Devin Peterson, director of the Flavor Research and Education Center at Ohio State University and a flavor chemist who was not involved with Wang’s research. “You're perceiving multiple different things that come together and are interpreted as orange.”

For OJ drinkers, it’s great news. The newly identified flavor modulators could mean juice with less sugar because the compounds can replicate sugar’s sweetness. Plus, the compounds don’t have any calories.

As the industry groups point out in their petition to the FDA, Brix alone “does not dictate great-tasting orange juice. There are other components that make up flavor.” When you take a sip of juice, there are individual molecules that can be singled out, like esters, which taste fruity, or others that taste bitter or citrusy, Peterson explained. Humans can’t perceive those molecules individually, so when you combine them together, it “creates a more complex profile” that we can taste, he said. If one quality is stronger than another, it can change what we perceive as the overall taste. “It’s like a symphony, right? If the trumpet’s too loud, it’s taking away from the overall performance,” Peterson said. The same goes for the examples of coffee and butter. For butter aroma, “I get blue cheese, baby vomit, mushroom, and I put those together and get butter,” Peterson said. In some of his research, he found that one important flavor modulator came from a surprising place: green beans.

It’s this combination of tastes and aromas that flavor chemists like Wang are primarily interested in. At the end of the day, she said, it doesn’t matter how much fruit is being produced if consumers aren’t buying juice. She and her colleagues published more research earlier this year testing whether certain types of diseased rootstocks can produce better-tasting fruit despite being infected. While the results aren’t conclusive, they found that one rootstock—a Changsha mandarin crossed with Benton citrange—produced the best-tasting juice among other rootstocks even though it had citrus greening disease.

Now that Wang and her colleagues know natural sweeteners exist in citrus, the next step is for plant breeders to incorporate them into new fruit varieties. For example, blending different types of sweet oranges with Valencia oranges creates a “really delicious” juice, said Lauren Diepenbrock, a University of Florida entomologist who advises citrus growers on management practices. Testing breeders’ creations is a fun part of the job for Diepenbrock and others at the citrus center in Lake Alfred. To find out which varieties will taste best to consumers, the center recruits about 100 people for “taste trials” involving different juice mixtures. The tasters give their opinions on how sweet, sour, or bitter the product is and how much they would pay for it. “In the past for the juice industry, we just had one or two varieties, Hamlin and Valencia,” Wang said. Now, the citrus team is testing many other varieties. So far, Wang’s research and other surveys indicate that consumers aren’t bothered by differences in juice varieties or decreased sugar levels—so long as the taste is right.

Thomas Spreen, a longtime Florida agricultural economist, says he remembers a time when post-Christmas grapefruits were so sweet that he didn’t need to sprinkle any sugar on top. He reminisces about the days when he and his wife would receive a box of large, healthy, and sweet citrus fruits on their porch for the holidays. “You can’t get that anymore,” he says. “It’s really sad.”

But Wang and her colleagues remain hopeful. Flavoromics isn’t a solution to citrus greening disease, but it is a way to keep the state’s struggling industry alive—and to make sure your morning OJ still tastes as sweet and citrusy as you expect.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club