Four Issues to Watch at the Upcoming UN Climate Talks

Inequality and finance are likely to dominate COP28 summit in Dubai

The opinions expressed here are solely those of the writer and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Sierra Club.

Next week, the 28th annual United Nations climate meetings (also known as COP, meaning “conference of the parties”) will kick off in Dubai, a city in the United Arab Emirates that is best known for luxury shopping, ultramodern architecture, artificial islands—and its oil wealth.

After this year’s wild ride on the climate change roller coaster—extreme fires, floods, and droughts, scientific reports that read like dystopian science fiction, and ever-widening inequalities between rich and poor nations—all eyes are on international leaders to step up and set things right at COP28.

So much is on the line. After decreasing during the Covid pandemic when huge chunks of the global economy shut down, greenhouse gas emissions are again rising to record levels. Despite a tremendous surge in renewable energy, the 2015 Paris Agreement goal of limiting global warming to 1.5°C (2.7°F) is in danger. That target was agreed upon due to overwhelming evidence of the dire impacts on people and nature if temperatures rise much beyond that limit. But we are still burning record levels of fossil fuels and international action remains minimal.

Given the string of broken promises coming out of recent United Nations climate meetings, some frustrated climate activists are calling for boycotting or even canceling these international negotiations. To some people, the COP sessions at this point maintain the fossil fuel status quo just as much as constructing a new coal-fired power plant.

And yes, you heard it right: COP28 will be run by the United Arab Emirates’ Sultan Ahmed Al Jaber, CEO of one of the world’s largest fossil fuel conglomerates in a country where 30 percent of the economy is dependent on selling oil and gas and rising temperatures are on track to make it too hot to work outside by the 2040s.

The climate extremes of 2023 combined with COP28’s deep political controversies require a clearsighted reading of where we are at and where we need to go. Here is a field guide to four critical fault lines that will make or break the meetings in Dubai.

The future is now

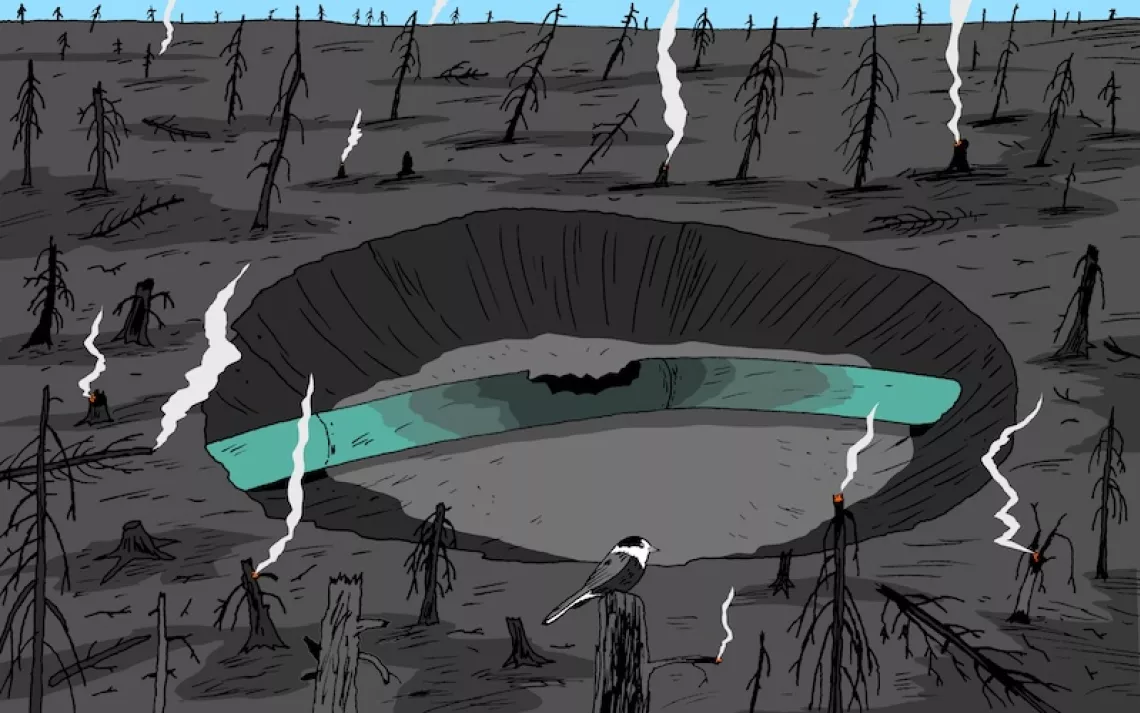

The first fault line running beneath COP28 is personal: The lived experience of hundreds of millions of people around the planet who suffered deeply, or lost, or came close to losing their homes and livelihoods when waters rose, fires raged, and droughts dried up crops in 2023. Only a few years ago, the climate change story was about how our children would bear the brunt of global warming and its impacts. This year is proving that the future is now.

Heat domes spiked record temperatures in Asia, Africa, Europe, and the United States. Fires burned forests in China, Spain, and Greece; huge Canadian wildfires consumed two and a half times more northern forest than in any year in recorded history. Ocean temperatures spiked. There were floods in 10 countries in less than two weeks—from desert Libya to tropical Hong Kong. Droughts shrunk rivers and crops in China and the Mediterranean Basin. And extreme hot and dry conditions have continued into November with temperatures 25° to 30°F above normal across Asia.

A few dead-enders may deny that these events are connected to climate change. Others, resigned to indifference, believe that they represent a “new normal.” Both perceptions are wrong. With greenhouse gas emissions still rising, temperatures will continue to increase until emissions reach net zero. More extreme events are on the way. The question is, what can world leaders at COP28 do about it?

Science, lost in translation

Even if climate denialism and obfuscation remain a hurdle to action, climate science is crystal clear. The increasing robustness of climate science reveals another deep fault line at COP28: The chasm between what experts portray as a planet in deep trouble and in need of transformative change and the political status quo of most national leaders who prefer to go slow.

Every climate study reveals that we are nowhere near on track to meet the goal of keeping global temperatures from rising more than 2.7°F (1.5°C). Instead, we are headed toward a warming world well beyond 3.6°F (2.0°C).

How can we avoid that dire scenario? In the seven years between now and 2030, we must collectively cut total emissions by 43 percent; immediately halt approval of any new coal projects; triple the use of renewable energy; construct and/or revamp national electrical grids to handle increasing loads of renewable power; cut methane (a potent greenhouse gas) emissions by 75 percent; and more rapidly develop and deploy carbon capture, utilization, and storage featuring new ways to suck CO2 out of the air.

Any one of these actions represents a challenge. Cutting emissions by 43 percent in seven years means reducing them every year by more than what occurred during the single year of deep Covid shutdowns. In 2023, the world burned more coal than ever in history; China alone approved two new coal plants every week. Reducing methane emissions is possible and dramatic increases in renewable energy may be within reach. But just to get the US electrical grid ready for renewable power and net zero will take building and refurbishing at least a thousand miles of transmission lines every year to 2035. And capturing, storing, and using carbon after fossil fuels are burned (the COP28 lingo is “abated”) is ultra-expensive and remains unproven at commercial scales.

These recommendations have been collected in a first-ever Global Stocktake for how to meet the Paris temperature targets; this summary will be discussed during the first days in Dubai. Consider it your handy scorecard to track progress on this fault line. Will countries agree to upgrade their emissions pledges? Create a targets-based action plan that encompasses science-based recommendations? Or will politically charged debates over “phasing down” vs. “phasing out” and “unabated” vs. “abated” fossil fuels stall out serious decision-making?

Whatever happens at COP28, the science shows we’ve entered a dangerous new stage of global warming—a fact that supporters of fossil fuels can no longer camouflage.

Follow the money

You may say, “OK, I’m on board. But what is all this climate action going to cost?” That very question forms the third COP28 fault line.

Here are the basics. There are three main categories of costs when it comes to climate action. We have to finance mitigation, COP-speak for reducing emissions to get to net zero; adaptation, to minimize harm caused by existing climate impacts and act to reduce future risks; and loss and damage, to offset historical costs from climate impacts that low emission developing countries can never pay for.

But financing climate action is complicated. There are multiple moving parts, various economic assumptions must be made, energy transition geopolitics are scrambled, and the politically explosive question of who pays hovers over everything.

There is no single, agreed-upon assessment for what will be the total cost of mitigation—maybe a trillion bucks? For adaptation, the trouble is that the wealthy, historically high-emitting countries have not followed through on pledges to help pay developing countries for reducing risks and building up climate resiliency. A just-released UN report shows that the “adaptation gap” is now 18 times what the developing world needs compared to what the wealthy world provides. And not a cent is on the table yet for loss and damage, since it was only last year that developing countries finally pushed wealthy nations to fund such work.

As for the question of who pays, it has to be some combination of wealthy donor countries, the developing countries themselves, the private sector, and the World Bank, International Monetary Fund, and other global banks. But right now, negotiations between these groups look like a foot race in which everybody is dragging their feet because nobody wants to win.

Not matter the exact figures, it’s at least clear that the world’s governments are hundreds of billions of dollars per year short of where we need to go and the gap is growing. Yet in 2023, countries collectively spent $7 trillion to subsidize fossil fuels, leading a World Bank official to quip, “People say that there isn’t enough money for climate, but there is—it’s just in the wrong places.”

It will be up to delegates in Dubai to get climate funding to the right places. You can track progress on this issue by looking for these COP28 outcomes. An agreement to phase out fossil fuels and fossil fuel subsidies on specific timelines. No more new coal projects. Timelines, targets, and dedicated funding for increasing renewables and reducing methane emissions. Ramped up financing to close the adaptation gap. New money on the table to address agricultural, land-use, and cement and steel industry emissions. Consensus on specifics about starting up the loss and damage fund with initial monies available before COP29 in 2024.

Call it inequality

How did we get so far behind the climate-action eight ball? In a word: inequality, the fourth COP28 fault line.

Rich countries seek to maintain their power in global political and economic decision-making. Developing countries demand a decent life for their people with electricity and heat. Businesses everywhere desire to boost profit margins. And rich-world people like you and me don’t want to give up our whopping share of Earth’s material resources.

All of this behavior is built on burning coal, gas, and oil. And now that world is on fire.

Fatih Birol, head of the International Energy Association, doesn’t pull punches: “There is no route to net zero without fair and effective international cooperation.” Which means we must factor equal rights and justice into our climate calculation. We can see that, despite China leading the world in today’s emissions, the United States bears the overwhelming share of total historical emissions. We can call out specific countries (the US, Russia, Saudi Arabia, and more) and businesses (Exxon, Chevron) that are doubling down on new fossil fuels investments. We know who in the United States persist in living “super emitter” lifestyles: Mostly, it’s households with combined incomes and investments of $160,000 or more.

Inequality will be a profound pressure point at COP28, since it shrinks the space where governments, corporations, and citizens can hide.

Developed countries will seek to substitute incremental action for transformative change. Oil-producing nations will push for more time to suck fuels out of the ground and sell them. The more these two blocs succeed, the less productive COP28 will be.

Developing nations therefore hold the key. They have increased power after forcing through loss and damage funding at COP27, but they still must have help with climate costs that they bear little responsibility for. Fortunately, their influence is growing; in a few years, more than half of global consumer economic power will come from the developing world. With equity, science, and the adaptation gap on their side, these countries will likely drive success at COP28.

Choose what you can do

Time is pressing. But every tenth of a degree matters in the quest to keep Earth habitable.

David Victor, an expert on climate action, concludes that progress will mostly be made through small subnational groups implementing innovative local and regional solutions. But successful local, state, and national climate projects in the United States, Kenya, Brazil, or any single country yield very little global leverage when China and India are burning more coal than the rest of the world combined. There is simply no substitute for United Nations meetings when the goal is to stimulate international climate cooperation. We have to fix the COP process, not abandon it.

So if you are excited about international action, follow COP outcomes and then vote for US leaders who espouse an America that meets its climate-focused financial responsibilities.

And consider climate action a challenge toward meeting your personal net zero. Plant trees locally, push for your city and state to construct and implement climate adaptation plans. At home, install a heat pump, get an induction stove, go solar, reduce your driving until you can afford an EV, and eat more plants and less meat.

The good news is that none of these actions are particularly innovative and all of them are essential. Whether we collectively meet a given temperature target or not, we still live on an abiding Earth. Whatever outcomes spring from COP28, everything everybody does will count.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club