The Global Climate Breakdown: A Reform Agenda for the World Bank and the IMF

A conversation with professor Avinash Persaud

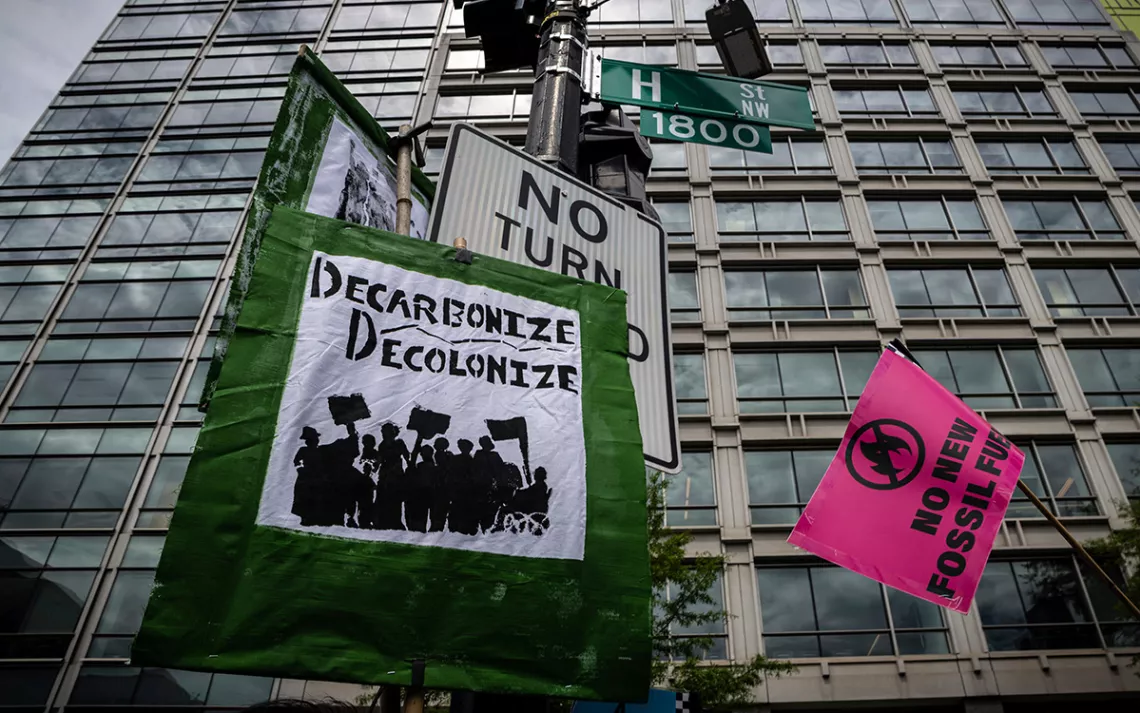

Climate activists march in Washington, DC, on April 14, 2023. Environmentalists with the Big Shift Global Coalition gathered outside the World Bank's spring meetings to protest the organization's fossil fuel financing and urge incoming president Ajay Banga to implement climate reforms. |Photo by Alejandro Alvarez/Sipa US via AP Images

Finance ministers from around the world met in Washington, DC, in mid-April for the spring meetings of the World Bank and International Monetary Fund with an unprecedented set of challenges before them. Accelerating climate change impacts, the lingering economic disruptions from COVID, food and energy vulnerabilities caused by the Russia’s illegal invasion Ukraine, and a growing debt crisis are all putting intense pressures on the economies of many developing countries.

When crises like these arise, the world typically looks to the World Bank and IMF for assistance. But their responses have been underwhelming at best, leaving many to wonder whether they are up to the task of confronting today’s most pressing global development challenges.

Professor Avinash Persaud is one of the leading voices calling for reforms. As special envoy on climate, investment and financial services to Prime Minister Mia Mottley of Barbados, he is one of the key architects of Prime Minister Mottley’s Bridgetown Initiative, an ambitious proposal to fund climate action and development goals that has received significant global support. Our conversation was edited for clarity and brevity.

Steve Herz: Calls for reform for the World Bank and the IMF are a perennial feature of these meetings. Over the last year, they have become more urgent and more ambitious in scope. What's happening now in developing countries that has generated such strong calls for reform?

Avinash Persaud: I think there are a few reasons why calls for reform are at a different level of intensity and are being responded to in a way that hasn't happened before. COVID and the aftermath in terms of all the supply chain disruptions has underscored what a connected world we live in. Before, that degree of connectivity was all a bit abstract.

We've also had the last 24 months of immense floods in Florida, in California, and elsewhere in America, and the heat waves in Europe, and the devastating floods in Pakistan. All of that made everyone feel they understood the climate problem. That they felt it. That there were some global issues that needed to be dealt with globally. And that responsibility for them could not be laid at the doors of individual countries, especially the world's poorest.

So I think that's why we're in this moment. And it is a special moment. It's never happened before, and it's not clear it will come again.

Professor Avinash Persaud |Handout Photo

Could you explain what the Bridgetown Initiative is and how it would address the current crises?

Bridgetown recognizes that countries and individuals are not doing what is in the best interest of our planet—whether that's about climate or development—due to finance. So, Bridgetown is about changing the finances. It's about five or six different practical things that are achievable over the next 12 to 18 months that could reshape the global financial system. At the core of them is reforms to multilateral development banks. But it's not the only thing.

Let's go through them. You have a pretty ambitious proposal to support emissions reductions in developing countries. You've written that it is much easier to finance renewable energy in the United States than it is in developing countries. Can you explain why, and what you're proposing to address that?

Well, in a way, we're calling for an Inflation Reduction Act for the world, because we need significant incentives to redirect private savings. In developing countries, the risks are perceived to be greater and so the obstacles are greater too. The majority of the risk is currency risk. International investors worry not about the solar farm, because solar technology is now pretty standard, but about whether the solar farm is earning in local currency and converting it back to dollars, maybe at a loss.

We can lower the currency risk because the multilateral development banks can take a super long view of that risk. And they can diversify across many different currencies to reduce that risk.

And you have a similarly ambitious proposal for resilience and adaptation.

The High Level Expert Panel on Climate Finance looked at the cost of the green transformation, the cost of sustainable agriculture, investments in natural capital, dealing with public health systems and a range of other things, and found that the developing world needs an additional $2 trillion per year. About three-quarters of that is connected to things that actually makes some money, like wind turbines.

We don’t have to invest government money in those, but create the right incentives and reduce risks to get that money there. Most of the remaining bit is investments in resilience. But when you invest in resilience, when you invest in a sea wall that stops tides destroying homes on the coast, the private sector won't do it because it isn't going to make money from it. But the government can borrow to do it because it will be saving money in the future if it is more resilient to floods.

So, the development banks can lend for this kind of resilience investing. And there's no point in developing countries becoming resilient in 25 years—they've got to be resilient today. That means bringing forward a ton of investments, and that might be too much to borrow. You would really sink under oceans of debt long before sea levels rise up. So the Bridgetown Initiative is talking about borrowing 50-year money for very low rates of interest—the same rate that the development bank itself borrows at. Today, developing countries get lent 10-year money at fairly high interest rates.

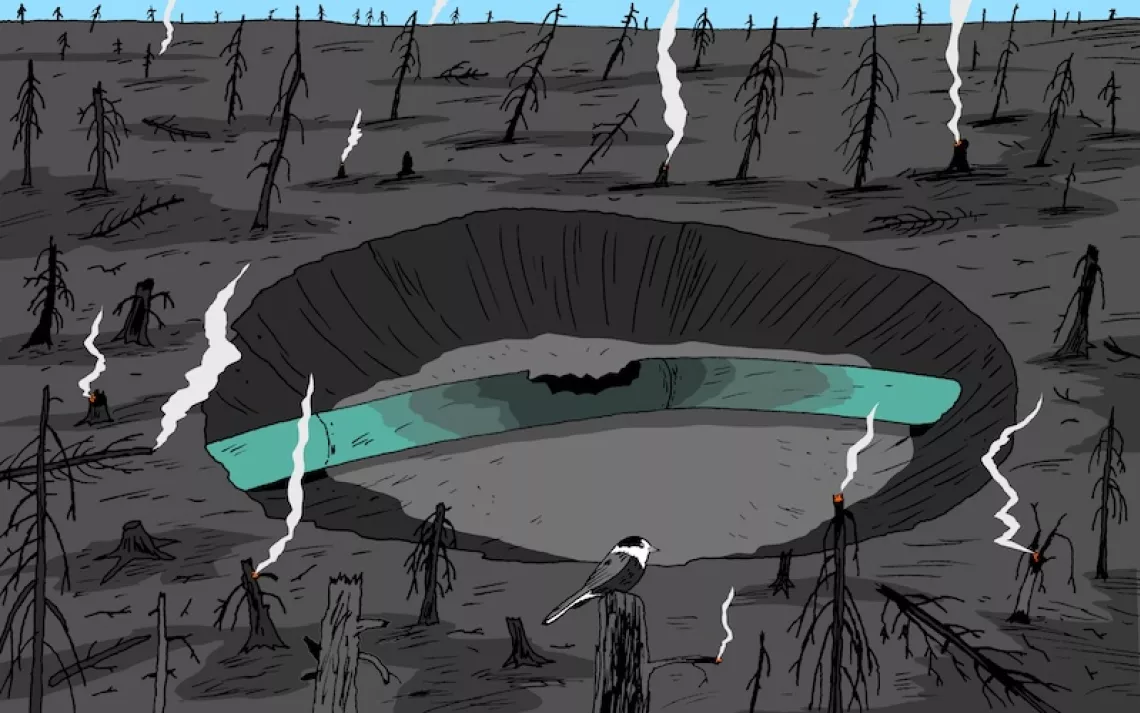

And we have to do that because even if we succeed at transforming the economy to low carbon, there's already a chunk of global warming that's baked into the system and already we need to be more resilient. There's a band around the equator, about 15 degrees latitude on either side, where 40 percent of the world lives and where the costs of climate change is four times the cost of anywhere else in the world.

In the northern countries, it's not really impacting their GDP. In Germany, the worst floods in living memory cost them 0.1 percent of GDP. When we had Hurricane Maria in Dominica, they lost 226 percent of their GDP in four hours.

To add insult to injury, climate change has nothing to do with them. Their emissions are often a fraction of 1 percent of global emissions.

“Climate change has the power to take someone who is not poor and make them poor. Something like a hundred million people have been shoved into poverty as a result of climatic events.”

You've made the important point that it's not only the poorest countries that are vulnerable to those kinds of shocks. It's also middle-income countries that are at risk of being impoverished by climate impacts. And so you've argued that climate vulnerability, not just income, should be a consideration when determining who should be eligible for reduced rate or “concessional” lending. What's been the reaction to that proposal?

Climate change has the power to take someone who is not poor and make them poor. Something like a hundred million people have been shoved into poverty as a result of climatic events.

Creditors understand this. Now there there's some people who already get concessional money who are rightfully concerned that we may be taking money away from their very important public health, education, infrastructure, and social services needs. That is nobody's intention.

Having listened carefully to that concern, we're not proposing a change to the concessional arrangement. But we are proposing that in addition to the concessional arrangement for the poorest countries, there is 50-year debt at low cost that goes to climate vulnerable countries when they're investing in resilience that will save them money in the future.

And where would the new money come from?

We need the multilateral development banks to really step up to the plate. They have become increasingly irrelevant in the global economy. We need them to triple the amount of lending per year. We need the World Bank, the biggest of them, to be lending a trillion dollars.

Because they are a bank, that does not necessarily require anyone to write a check for $1 trillion. They have something called “callable capital,” which is where somebody basically says, “I'm not giving you any money, but were you to be on the verge of going bust, I will give you money.” For a triple-A-rated bank, the likelihood of that being called in is very, very low indeed. But it could go a long way toward allowing the banks to treble their lending.

Unsustainable debt in developing countries has risen to levels we haven't seen in quite some time. Can you explain how climate impacts have fed that that crisis?

The level of debt before COVID in developing countries was already high. And COVID has made that even worse. And then you add to that rising US interest rates and a stronger dollar. That's the genesis of this debt crisis. Over 50 countries are in serious debt difficulty.

One of the strong patterns of debt has been climate vulnerability. In the Caribbean and the Pacific, around half of all new debt is actually related to mopping up natural disasters.

Dominica's story is interesting. Ten years ago, they got hit by Storm Ophelia that wiped out about 40 percent of their GDP. And then four years later they got hit by Storm Erika that wiped out 95 percent of their GDP. And then two years after that, they got hit by Hurricane Maria, which wiped out 226 percent of their GDP.

Imagine if they had to borrow money each time to rebuild. They'd be bust. And so it's not surprising that the Caribbean countries are one of the most indebted regions in the world. And when we go to the creditors, they say, “Oh well, you need to be much better at managing money and is there any corruption going on in your country? Because I don't understand how come you’re so indebted.”

And it's doubly insulting because the debt and the climatic event is a result of what other people have done. And so that's why we're arguing as part of Bridgetown that loss and damage from climatic events have to be funded by international grants, not funded by increased debt.

The other thing they tried to sell us is insurance. I mean, that’s an amazing kind of insurance, right? Somebody’s pelting stones into your back garden and when you object, they say you should insure yourself.

So we are saying, we're going to create a special agency that's going to guarantee risks and encourage the private sector to come in. We're going to get the multilateral development banks to lend more and use callable capital. The amount of grants we're talking about is much smaller than otherwise, but we still need some grants specifically for the one thing that the private sector won't give you money for.

And we need international taxes to fund a loss and damage fund. We need maybe a charge on the emissions the shipping industry contributes. We need maybe a contribution from the fossil fuel industry. They made $4 trillion last year. Pakistan lost $40 billion. A third of their country were homeless. Thirty million people and 27,000 schools were underwater. So 1 percent of fossil fuel revenues would have gone a long way to paying for loss and damage.

“One percent of fossil fuel revenues would have gone a long way to paying for loss and damage.”

The World Bank has put out its own proposal for change called the Evolution Roadmap. Is it adequate to the challenges that you've just laid out?

Well, the good thing about it is that it shows that the bank has a genuine and deep understanding of the challenges. But Bridgetown is about is scale. US Treasury Secretary Yellen put it very nicely last year when she said we need to go from billions to trillions. And yet, the World Bank’s Evolution Roadmap is all about all the good things we're doing, and how we could do them a bit more. And I think they're missing scale.

How will the reform agenda play out over the rest of the year?

A key part of policy entrepreneurism is to listen carefully. To keep on shaking the door handles to see which doors are actually opening and which are firmly shut. The Bridgetown Initiative is identifying those doors that are opening. We need to push hard on them because collectively this really changes everything.

When it comes to the multilateral development banks, we do need to use things like callable capital to make sure that we are lending as much as possible. And we need to be helping countries become climate resilient and making super long-term debt low cost. I think these are achievable things over the next 12 months.

In addition, we need to create a new agency that will lower the macro risks of investing in developing countries. And I'm hopeful that that we will make progress on a pilot agency before the end of the year.

One of the other things that is getting most momentum of the Bridgetown Initiative is natural disaster clauses. Imagine you're in a flood area and you've got a mortgage that has a clause that says that if you get flooded, you don't need to pay the interest and the principal for a couple years. Take that money and spend it on the damage. But you do need to pay it back later, and the mortgage suddenly becomes two years longer.

This isn't an abstract theory; we have them ourselves. Barbados is the largest sovereign issuer of bonds with these clauses. The UK Export Credit Agency has put it into their export credit agency instruments, and we're looking for other public sector banks to do it.

Has the Biden administration supported these reforms?

The Biden administration has marked itself out in a different way than previous administrations. The president himself is listening. Genuinely listening. What often happens to climate vulnerable countries is we go to places to be lectured that we're indebted because we're not running our countries well.

But the Biden administration has helped to set global ambition. Saying we need to go from billions to trillions, that wasn't a developing country voice saying that. It was Janet Yellen, US treasury secretary. And the United States was quite important in pushing the bank to come up with an Evolution Roadmap, and in sending a signal with regards to the leadership of the bank that they’re serious about change. So we are grateful and appreciative of those things.

The US administration is also, though, concerned about what it can or cannot get through Congress. And that means the US is both a positive force for change but is also a force for no change.

One political issue is that countries like China and India say they want to put more money into World Bank. The US says, “No, I don't want you to put more money in because if you do that, my share will fall below the veto level.” It seems to me that if the United States wishes to effectively own these institutions by maintaining a veto, it really needs to make sure it's contributing. I think the United States doesn't appreciate how other countries view that.

Can you put these proposals for finance reforms into the broader context of climate justice?

America’s carbon intensity has fallen, and it will fall further with the IRA. America is pointing its finger at China and India and saying, “You are the problem today.” China and India are saying, “Global warming is caused not by today's emissions; it is caused by the stock of emissions.” They are pointing their finger at America. So you’ve got these people pointing their fingers at each other.

And in the middle, climate-vulnerable countries are burning up. So we've decided that rather than emphasize the justice issue—which is a genuine, legitimate issue—we will find a solution by finding the finance to transform the world, instead of saying who's to blame.

I fully get the justice story. I fully believe it's right. I'm happy for people to talk about it. But it's not going to move us any further. In fact, it's stopping us from moving.

We need a global coalition. And so the issue for me is not, How do I get developing countries concerned about this? Because they're seeing it all the time. It is, How do I get developed countries to fully buy into this?

The way I'm trying to bring them into the coalition is to say this is good for American business. This is good for American technology because the whole world is now going to be investing in this.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club