How Can We Save Threatened Wild Bee Species?

One scientist thinks farmers, equipped with an app, can help

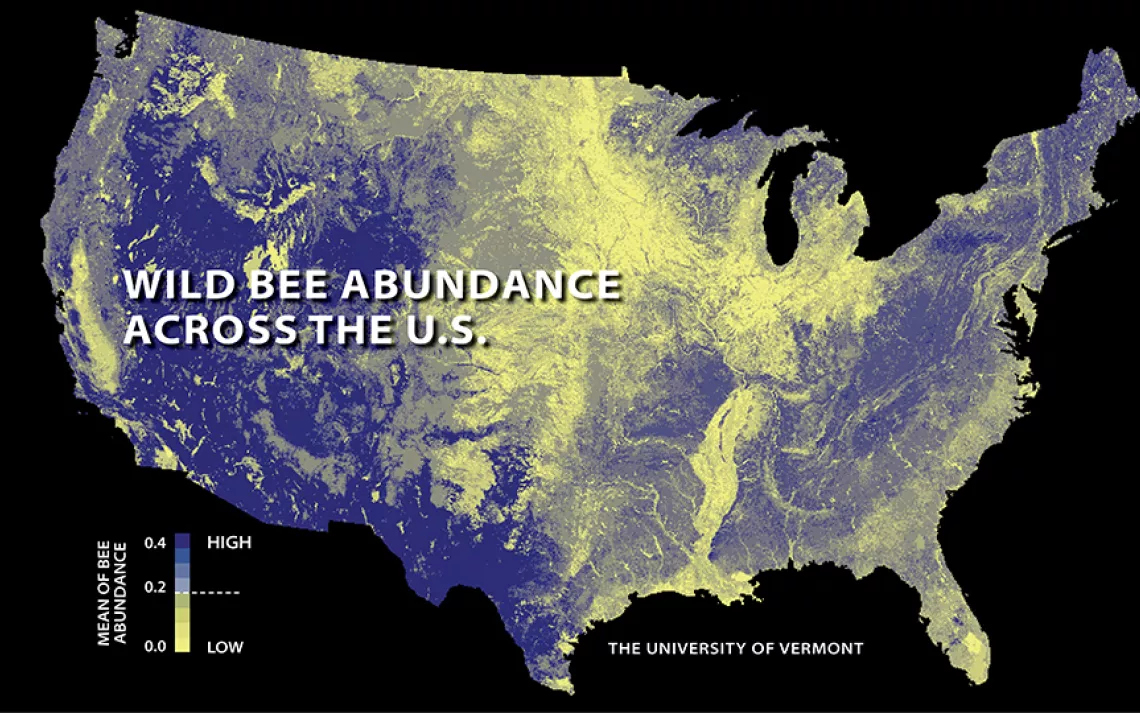

University of Vermont bee expert Taylor Ricketts and his team created the first map of wild bee abundance in the U.S. | Photo courtesy of University of Vermont

There are more than 4,000 wild bee species native to North America and Hawaii. Of the nearly 1,500 the Center for Biological Diversity has tracked, over half are in decline, the group reported in February.

These are mostly solitary, ground-nesting bees. Unlike honey bees (which are native to Eurasia), they’re not domesticated and don’t build hives. Although humans do not manage them, wild bees still provide more than $3 billion dollars in fruit pollination services to U.S. farmers each year.

Taylor Ricketts, a bee expert at the University of Vermont, believes this relationship between agriculture and wild bees makes farmers natural allies in the effort to protect these imperiled pollinators.

In 2015, Ricketts and his UVM team created the first-ever map of the country’s wild bee abundance. They identified 139 counties in major agricultural regions where wild bee populations are falling even as crop-pollination demands are rising.

This unsettling mismatch between pollination needs and agricultural practices is due, in large part, to agriculture itself. Habitat loss and pesticide use associated with agriculture are driving bee declines. Other drivers include disease, urbanization, and climate change.

Now, Ricketts wants to empower farmers to address this contradiction and make bee-friendly decisions with a web app.

Though still in early development, the app will eventually walk farmers through different land-management choices and cost-benefit analyses, so they may make the best decisions for both bees and their bottom line.

“We actually know a lot about how to help bees and what to provide them on landscapes so they can continue to persist there alongside us,” Ricketts says. “But we needed to package that up into a tool that could help farmers manage lands.”

The app is a wide-ranging collaboration between Ricketts, Eric Lonsdorf of the University of Minnesota, and the Philadelphia software company Azavea, among others. Its recommendations will be specific to individual farms, ranging from restoring pollinator habitat to adding more domesticated honey bees.

A farmer could benefit, for example, from converting less-productive areas or edges of fields to wildflowers, “a mix of plants that supports pollinators all year, so that there is always some resource available to bees,” Ricketts says.

The economic and ecosystem effects of such choices depend on a farm’s existing landscape, location, and crop types, hence the necessity of being able to customize the app.

Research shows that the benefits to wild bee populations can be significant. In 2009, Michigan State entomologist Rufus Isaacs and other researchers seeded 15 perennial wildflower species beside highbush blueberry crop fields in Michigan. After just three years, their study saw a significant increase in yields from plants next to the wildflowers, compared to controls. Added revenue from increased yields offset the cost of the plantings.

Isaacs heads up the Integrated Crop Pollination Project (ICPP), a $6.9 million dollar USDA grant initiative that funds the pollinator app and numerous other initiatives. The grant aims to create context-specific recommendations for promoting crop productivity and wild bee populations in the U.S.

As of now, the app does not address pesticides, which are threats to both honey and wild bee populations. A 2013 U.K. study linked wild bee and biodiversity declines to the use of neonicotinoids, the most common class of insecticides in the world.

Ricketts stressed that the app is still in its infancy. He hopes to incorporate pesticide use and other, more complex management elements once it has been released.

Katharina Ullmann, a crop-pollination specialist at the Xerces Society, handles outreach components of the ICPP. She says that in the future, there will also be promotional and training infrastructure around the app to ensure growers and other parties know about, and know how to use, its tools. But the team isn't ready for rollout just yet.

“We have a prototype. We’ll be taking some time for people to test it," Ullmann says. "The main goal right now is to make sure it’s working well and user friendly."

What You Can Do

Help Save Our Bees and the Planet: Ask Congress to pass critical protections for pollinators. Toxic pesticides called neonicotinoids, or “neonics” are killing bees and putting ¼ of what we eat at risk -- as everything from apples to watermelon depends on bee pollination. American beekeepers reported an estimated loss of 44 percent of their hives last year. Congress must put an end to this crisis. Tell Congress to pass the "Saving America's Pollinators Act."

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club