Life Lessons in Activism—and Parties

A brief guide to changing the world without burning out

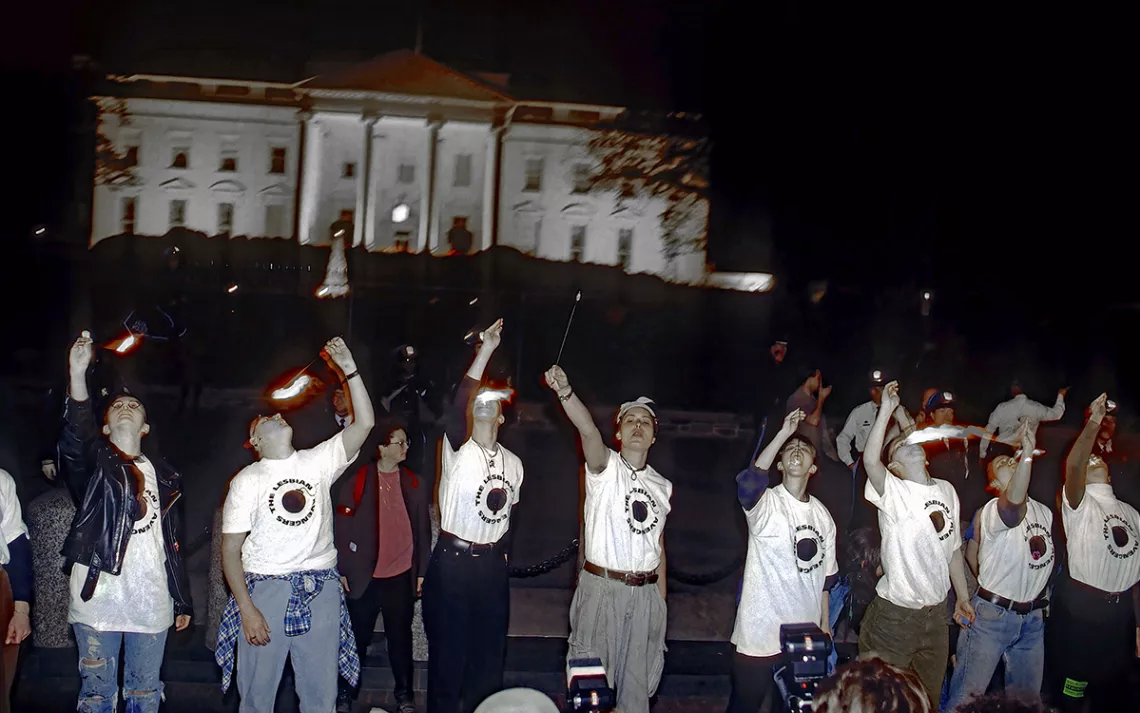

Lesbian Avengers eating fire in front of the White House in 1993. | Photo by Mark Reinstein | MediaPunch/IPX

I often tell people who ask me about my life that I was the unlikeliest candidate for a lifetime of activism. I was born in the United States in 1958, to parents who were Haitian and French. They were both survivors of the Nazi occupation of France, and they always urged me and my siblings to keep our heads down when it came to politics. Leave it to someone else, was their message. Don’t get hurt.

In the early 1980s, I graduated from the Columbia School of Journalism. Without much of an idea of what to do or who to be, I started my reporting career in Haiti. I reported on the pro-democracy movement and cases of political disappearance. That’s when I learned that hope is not an abstract slogan but a powerful weapon.

As a reporter, I saw that the poorest of communities had talented leaders. I saw so many young people willing to risk a better future and thousands of families dancing in the streets when Baby Doc and his wife, Michelle Bennet, were ousted from the island.

My mantra was and remains that the political is very personal. There wasn’t much room to be neutral about AIDS. Even though I was a journalist, when the call was for bodies in the street, I went. That step was always one I’ve had to juggle: Where am I best suited to be of use at this moment? Documenting or putting my body on the line? Often, it was to sit down and force the police to cuff me and drag me away. Later, I’d file my stories.

Along the way, I’ve forged connections and enduring relationships that have sustained me, including the anti-nuke 1980s Seneca Women’s Peace Camp, ACT UP, Women’s Pentagon Action, the Women’s Action Coalition, and the Lesbian Avengers. Scratch the big protests in recent years and you’ll find people like me, sometimes as leaders, sometimes in the rank and file, sometimes providing security. Now our kids are beside us, whether it’s at the Women’s March, #NoDAPL, or #BlackLivesMatter. Here's some of what I've learned along the way.

Action is the antidote to despair

People often ask: How do you get started? How can you choose what action to do? There are so many issues. It’s overwhelming.

My answer is simple: Start with what you know best, which is yourself. Identify what you care about the most and what resources you may have or lack to bring to a given problem. Allies and experts may already exist in your local community. Start there. In the 1980s, I learned about intersectional politics and organizing at the Seneca Peace Camp from mentors like Grace Paley, who urged activists to examine the structural inequities underlying any issue. That would reveal who was likely to be affected and where natural allies might be found. It’s a far better way to find committed allies than to badger others about the rightness of your cause. I call it the politics of attraction.

Consider your privilege and use it to help those with less of it

As a blan, or white person in Haiti, coming from America, with insider access as the American cousin of a prominent Haitian family, I was safer than local Haitian journalist colleagues. I could ask hard questions and wouldn’t necessarily be jailed or killed. Today, I remind white activists like myself: We have unearned skin privilege. We need to both check our privilege and make use of it for the cause.

If you plan to turn up as a white ally in a Black Lives Matter protest, ask yourself, “What’s my role here? What do the organizers want us to do?” There may be many responses. Maybe you should not be standing at the front but in the back or at the sides, creating safe space and providing a buffer line between organizers and the police.

Be aware that brown or Black activists will face more violence at a street protest and in jail. So listen to POC activists and their leadership when they tell you what they need. Maybe they can’t get arrested, or they don’t have papers, or they’re not out in their communities as gay, lesbian, or trans. Educate yourself, listen to those who are the targets of systemic abuse, and be willing to be uncomfortable when your privilege and voice are challenged.

It’s also important to be humble. Not all issues are yours to lead the fight against. Learning to be a good ally and do solidarity work means active listening and a willingness to be uncomfortable, to look critically at your position and views.

You can teach yourself what you need to know

Back in Haiti, I’d seen a rash of tuberculosis and malaria cases later revealed to be AIDS-related. By the time I was reporting on the AIDS crisis in the United States, I’d embarked on a self-taught crash course in medicine and science because my close friends were dying. I worked with my friend Kiki Mason, an OUT magazine contributor who founded Lesion Liberation, to demand pharmaceutical trials for possible drugs to treat Kaposi’s sarcoma and blinding cytomegalovirus.

Whoever you want to help, and whatever the community or cause, the most affected are usually the experts on the issue. They can tell you what they need and identify the hurdles to access. Chances are, others in your circle or community have organized around the issue, so learn from prior efforts and take the lessons they offer.

In ACT UP, and later the Lesbian Avengers, I also learned how to think strategically about action: What is the problem? What are the key hurdles? Who are our allies? Who are our enemies? What do we want to change, and who is our target? It’s not necessary to know the answers, but be willing to ask questions, and to realize solutions exist.

Meet other activists where they are

People come into social and political movements at different points in their personal journeys. A good organizer and process create a safe space for an individual to figure out their next step and be supported. They invite those who haven’t spoken or who are new to speak up. Learning to create safe space for others to participate and lead is vital to good organizing.

Not everyone will be ready to do every action, or to risk arrest, but they can research an issue or write a press release. They can help lawyers do legal support and track who’s being dragged away or what officer arrested them. Everyone brings resources and has insights to share.

Disagreement and debate can be healthy, when grounded in respect and listening

ACT UP and the Lesbian Avengers rotated facilitators and often paired them so that less-experienced members could develop facilitation skills. Anyone was invited to suggest actions—but if they raised their hand to suggest something, they also had to be willing to help organize it if it was adopted. We asked members to speak on the pros and cons of ideas, with the understanding that while debate is healthy, personal attacks are not.

Many people often disagreed on targets, tactics, slogans, and more. But at some point, there was enough discussion, and it was time to vote. Majority vote, not 100 percent consensus, was the decision-making tool.

Play and self-care are a part of activism

What no one prepared me for when I began to join protests was the daring fun and the exhilaration that I felt. We '90s activists were very aware of the need for self-care and play as critical components to balance the losses and ravages of AIDS. Our movement graphics and slogans and fashion and theatrics were bold and fun and sexy. We danced as much as we protested.

The Lesbian Avengers taught one another how to eat fire in 1993 after an arsonist killed Hattie Mae Cohens and Brian Mock, a lesbian and a gay man, in a firebombing. We would chant, "The fire will not consume us. We take it and make it our own.” It left a slight taste of kerosene in my mouth and a sense of excitement and pride and sisterhood. One night I watched a line of red-caped Lesbian Avengers pass lighted torches from tongue to hand to tongue with the backdrop of the Washington Monument behind them. It wasn’t exactly running away to join the circus, but it felt like the next best thing. Celebrate every battle, and balance the long fight with regular fun.

Small steps build to bigger actions that can transform our future

I’ve seen it happen many times. Haitians ousted a dictator and wrote a new constitution. ACT UP fought to secure lifesaving treatments and put a face on patient advocacy. The Avengers started the Dyke March with other lesbian groups, and today, these marches happen globally. There were many losses, but the victories have led to today’s world.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club