Puerto Ricans Face Uneasy Future After Hurricane Maria

Questions loom about damaged infrastructure and a coal ash landfill in Guayama

Abi de la Paz de la Cruz, 3, holds a gas can as she waits in line with her family to get fuel in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria, in San Juan, Puerto Rico, on Monday, September 25. | Photo by Gerald Herbert/AP

As Hurricane Maria approached Puerto Rico on Tuesday, September 19, Adriana Gonzalez prepared as well as she could. She readied her campstove, a supply of canned food, and two seven-gallon jugs of water. By late afternoon, she and two friends hunkered down in her apartment in San Juan.

They had a restless night. At 11 P.M. the power went out. At around 1 A.M., they woke up to a roaring wind, followed by the sound of trees breaking. “They make a really specific sound, like thunder,” Gonzalez told Sierra by phone on Monday. A large branch fell from the mahogany tree in front of her house.

By 6 A.M., it was raining hard. “It looked as if someone was dumping buckets of water from the sky,” Gonzalez said. Despite the aluminum-shuttered windows and the precautions she had taken to keep them tight, water started pouring into the apartment. “It was like someone was hosing down my windows from the outside,” she said. They used all the towels and sheets they could find to sop up the water.

Later on Wednesday, the storm had tapered down enough for Gonzalez to step outside. She emerged to see a world upended—debris-filled, flooded streets and damaged buildings. Overall, she counts herself lucky to have made it relatively unscathed through the worst hurricane to make landfall in Puerto Rico since 1932.

Now, like many other residents in the capital, Gonzalez is waiting to see what happens next. “Today we have better cellphone service,” she said. “Tomorrow we might get water back.” Much remains uncertain. With a curfew in place from 7 P.M. to 5 A.M., the overall mood of the city is tense.

Most of the island’s 3.5 million residents are without electricity and could be for months, though Puerto Rico’s aging electrical system is so unreliable that many people, especially business owners, have their own generators—a perverse kind of bright side to the current predicament. On the radio, stores and restaurants in the capital are announcing that they are open for business.

But all of those generators run on gasoline, which is scarce. “Gas is on everyone’s minds,” Gonzalez said. “Yesterday, I saw one gas station that had a hundred cars. People were there with their chairs, playing dominoes.”

According to government officials, there is no actual gas shortage. The problem has been transporting the fuel to stations. But the long lines feed people’s anxieties: “You see all these people waiting for gas,” Gonzalez said, “and you think that there is a crisis and you need to go get some.”

The lack of communication with the rest of the island is also producing widespread anxiety. Cellphone service is still extremely limited. “People are starting to get desperate to hear from their family members,” Gonzalez said. The news reports are grim: Entire towns along the coast destroyed; towns on the interior suffering major landslides; people running out of food and water as they wait for aid that has yet to arrive. “We know that there are supplies, but people are not seeing them because distribution is very slow,” Gonzalez said.

After the storm subsided, the rain continued for two more days, dumping up to 40 inches on some parts of Puerto Rico. Some of the worst flooding was in Toa Baja, where officials opened the gates of a nearby dam while the city was also experiencing a storm surge. At least eight people died.

As an environmental justice organizer with the Sierra Club, Gonzalez is worried about other problems as well. “What happened in Toa Baja is terrible, but the town also has a huge oil refinery. There has been no conversation about that plant—did it flood? There is a total lack of information about possible contamination.”

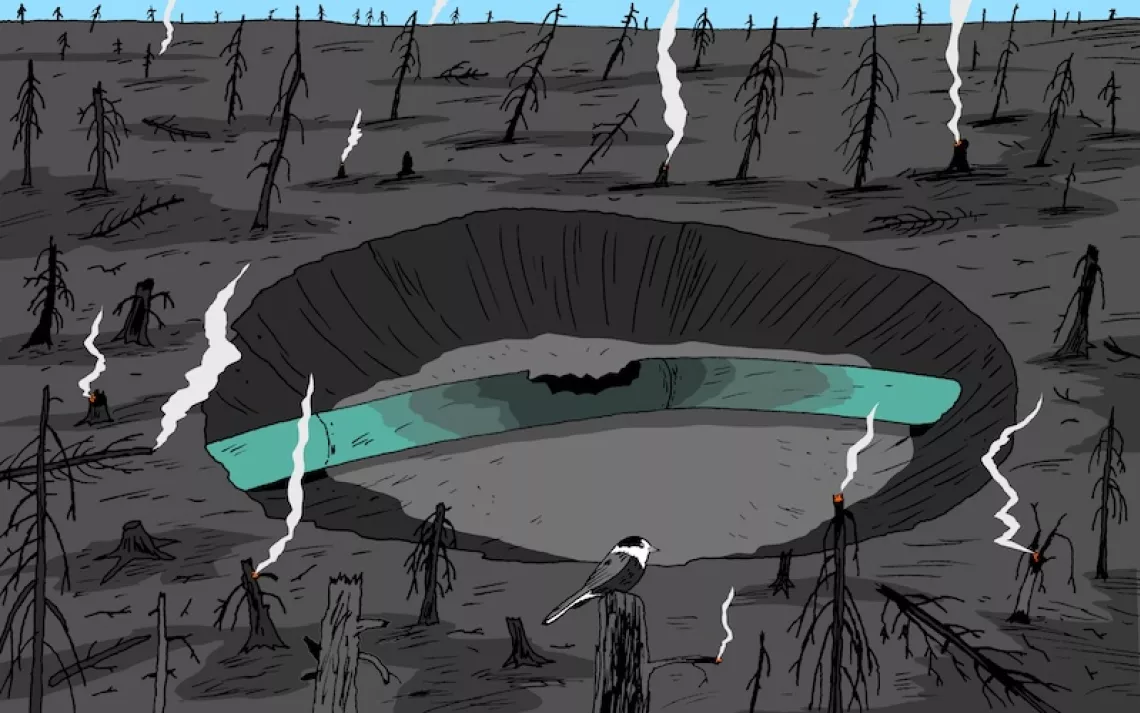

Another concern is a mountain of coal ash at a landfill in Guayama. The secretary of the Environmental Quality Board released an official statement saying that the site had not flooded and that the coal ash had not blown away in the heavy winds, but Gonzalez is skeptical. She’s been texting contacts in both Toa Baja and Guayama but has yet to hear back from anyone.

Questions about the long-term recovery effort loom. FEMA normally requires localities to pay 25 percent of the emergency funding it provides, but Puerto Rico was in an economic crisis before the hurricane season started and will not be able to afford it.

Agriculture on the island was devastated, which means Puerto Rico will become even more dependent on imports. Gonzalez is already thinking about ways that she and the local chapter of the Sierra Club can help farmers recover.

She’s also thinking about how to rebuild communities so that they are more resilient in future hurricanes. “We’re not just looking at rebuilding but also at transforming what we had,” she says, “because it’s the only way that we’re going to be able to move forward.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club