Finding—And Potentially Losing—Ourselves in Firelight

An astrophotographer’s pictorial homage to International Dark Sky Week

As the snow melts in the Northern Hemisphere and winter-weary humans emerge, blinking in the harsh light of springtime, we arrive at the most exciting perennial event of the year. No, not the start of baseball season, nor the springing-forward of the clocks. I’m talking, of course, about International Dark Sky Week—that stretch of April (kicking off tomorrow and lasting through April 12) when humans obsessed with outer space get to beg anyone who’ll listen to go outside and look at the sky, because Wow! And also because that view—and everything it has to teach us about the history of the universe—is imperiled.

Humanity’s rapid spread to the far corners of the globe threatens to blot out the wonder of the sky, and that’s because humans increasingly rely on artificial lighting to live. The Dark Sky Movement was born in the late 1980s as a response to the nation’s light-pollution problem. Light pollution, from the photons we create to facilitate our culture and productivity, not only forms an ever-burgeoning barrier between the reality of the cosmos and our imaginations, but it also uses massive amounts of energy, affects plants, and wreaks biological and psychological havoc on many species (including humans) not wired to filter it. Simply put, we’ve systematically blinded ourselves to the natural world with a curtain of our own creation—and we’re coming to terms with the cost.

Those of us preoccupied with the night sky live in a state of ever-present, low-level panic. Thanks to initiatives like International Dark Sky Week, the public is becoming more cognizant of the threat. The idea behind the initiative is to celebrate the majesty of the sky and also educate the public about ongoing efforts to promote energy-efficient outdoor lighting, and to designate formal dark-sky preserves—protected areas, found in national parks and in municipalities (like Flagstaff, Arizona, and Borrego Springs, California) that have committed to down-cast lighting, better-focused lights, and other forms of light-pollution abatement.

Light Pollution’s Origin Story

Like many people living through the pandemic, I’ve spent a lot of time this year retreating from cityscapes into the wilderness, where I like to stare deeply into campfires, trying to wrestle fundamental truths, like why we have light pollution in the first place, from the flames. Humanity’s first triumph over nature, the harnessing of fire created the space for civilization as we know it to unfold. Our past remains elusively at hand in campfires; just by staring into them, you can viscerally sense the early tendrils of curiosity, language, and cultural mythos that brought us out of nature.

A few months ago, after an afternoon spent binge-eating fried calamari and oysters Rockefeller, I found myself staring into a fire I’d built in Big Sur, California, attempting to reconcile feelings of deep connectedness to the history of humanity with rumblings from a sudden-onset case of omnidirectional gastrointestinal explosiveness (med school was awhile back, but I think that’s what it’s called). The heat and glow of the fire stretched only a few feet before me and my girlfriend but contained a world of human-made safety.

Early humans used fire to emerge from the wilds, and wherever we set up camp, we freed stored sunlight from wood, creating tiny bubbles of day in the middle of night. The fires we light are the resurrections of days long past. Most of the light we make—from burning wood to oil to coal—represents the sunlight of countless yesterdays, captured through photosynthesis and released through combustion. Humans have utilized such natural batteries since the dawn of time, and our culture is still powered by the ghosts of yesterday and illuminated by ancient sunlight. These were the thoughts gurgling through my mind as I sipped my ill-chosen warm peach/mango seltzer. Bubbles. Photosynthesis. Oysters and mango.

In lighting a campfire, my girlfriend, Katie, and I replayed one of the most basic acts of being human: We created our own, separate world, where we could forget about the darkness, fear, and creepy crawlies in the night. Crawlies. Fear. My stomach churned and I remembered my body; fire could help me shut out nature but not escape it entirely. Still, I felt at ease in the comfort of our creation, and tried to distract myself by wondering how many of the best ideas in history were born in the glow of fire. We almost certainly found ourselves in fire; could we lose ourselves there too?

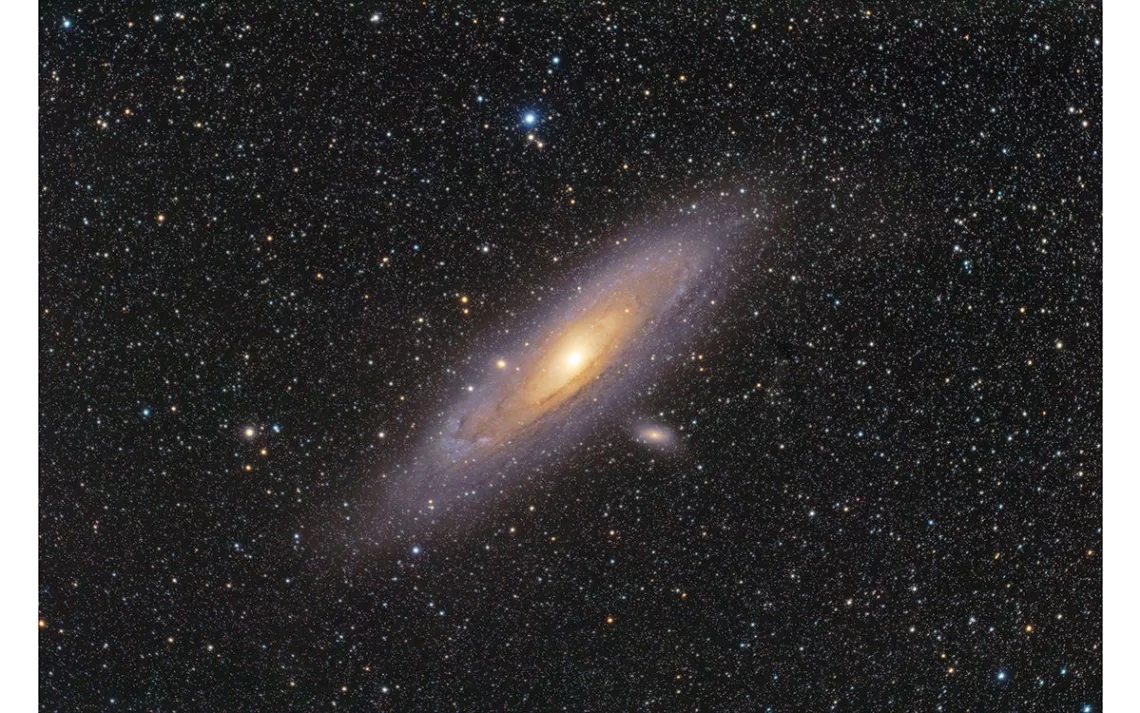

When I looked up from the fire to contemplate this thought, I saw the price I’d paid for this cocoon of safety: I could barely see the stars. As an amateur astronomer and astrophotographer, I’ve grown reliant on the dopamine hit that comes from the faint glow of the Great Orion Nebula, or from recognizing the lonely smudge of the Andromeda Galaxy, 2.5 million light-years distant. But all that was absent thanks to the protective glow of the fire; I could see only the brightest stars. The tendrils of gas and dust that normally illuminate dark skies in remote places like Big Sur were drowned out by the consequence of my humanness. And why was I making so much saliva?

I excused myself from the fire so my body could remind me of my mortality. As I recovered, I gazed up again and realized my eyes had finally adjusted to the brilliance of the cosmos. I could see a stark and unfiltered rendition of the universe, reminding me of much more than my body ever could. It turns out that the spectacle that sparked origin myths around the world and drives our continued exploration of reality sits just outside the glow of our fire. Simply by walking away from that unnatural brightness, the calling card of my species, I was able to experience the wonder of Deep Time.

When I crawled back to the campfire, my retinas became once again awash in a sea of light of my own creation, and the spectacle receded. The feeling I’d had looking at the sky faded with my night vision, and all I had left was the echo of the experience, raw but past. That world and that feeling remained outside; such matters can be remembered and woven into our narratives and social fabrics, but they can’t be experienced fireside. They’re vital to our understanding, yet one must escape our own glow to experience such grandeur and humility.

Our world—the human-made world—was born around fire, and as our fire grows, so does our capacity to forget what lies beyond its reach. We live in a time when some lucky humans can benefit from the luxuries of the modern world yet still choose when to step away from the glow of our collective fire to appreciate the galaxy. I count myself among those most fortunate, and I’ve taken to bringing specialized instruments—telescopes and cameras—as far from our glow as I can in hope of capturing and preserving the rare and delicate photons normally drowned out by human activity. Astrophotography allows me to return to our campfire with artifacts from the outside world and provides me with a way to re-experience and share some bit of the wonder I feel when lost in the sky. But it’s not enough—just like watching an alligator in a zoo is no substitute for visiting the Everglades, seeing a slick image of the sky can never replace the visceral sensation of seeing the universe, unfiltered.

And so, once a year, humans like me are given a little elbow room to remind anyone willing to listen that now is the time to act (and apparently, to talk publicly about an avoidably tough tummy time I had while camping). Our civilization uses ancient sunlight, stored in fossil fuels, to turn night into day and to fuel the growth of our collective fire. Up to now, we have mostly powered our world with the sunlight of the past and, relatively speaking, we're just now starting to come to terms with the cost of this choice.

While the loss of the night sky may seem like one small component of our ecological catastrophe, it is emblematic of our newfound inability to escape ourselves. As it becomes harder to step away from our campfire, it also becomes more difficult to escape the reality of our many other impacts on the planet. This generation faces a stark choice about how brightly we want our fire to burn. If we choose wrong, the wonder of the sky could become a memory, and our human-made fire may be all that’s left.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club