Michael Nichols’s WILD: A Frenetic Look Into the Animal Kingdom

The celebrated photographer’s latest book chronicles his decades-long career

Photos by Michael Nichols

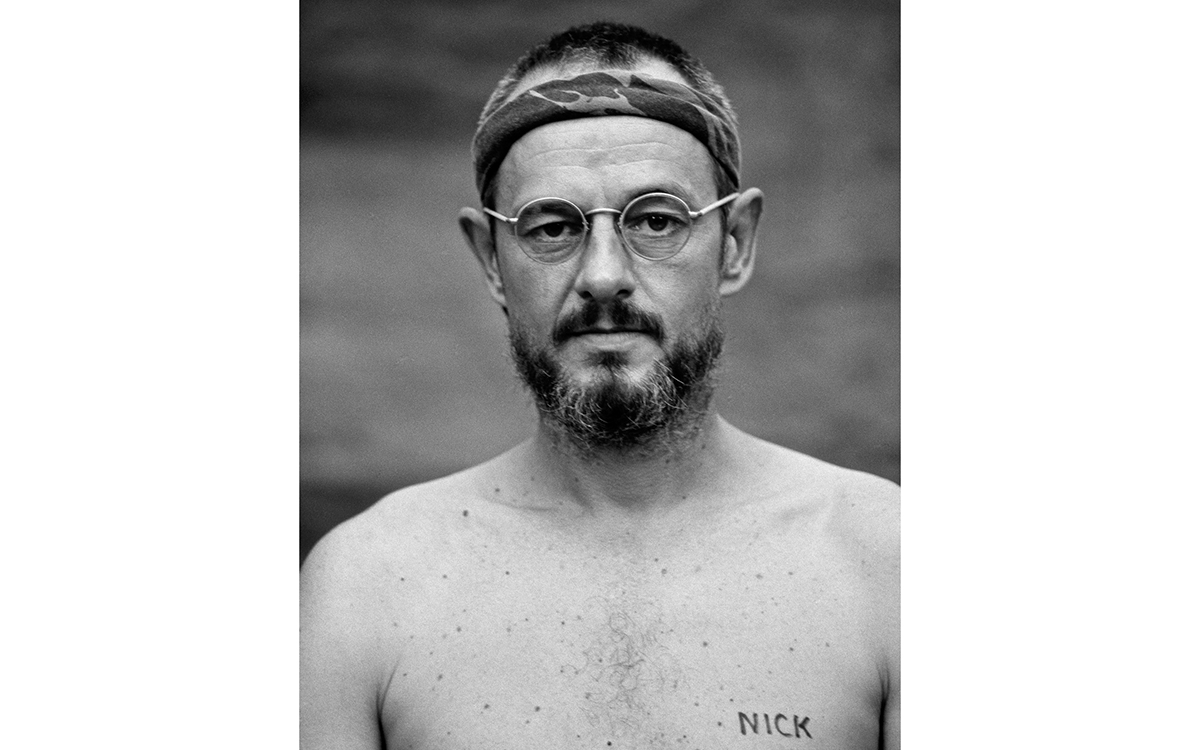

A northern spotted owl gliding through a dense redwood forest. A tiger leaping off the fringe of a rocky cliff. A bear wading in a shallow pond. Award-winning photographer Michael "Nick" Nichols has dedicated his entire life to capturing the frenetic rush of the animal kingdom. His favorite photos from that decades-long endeavor are now available in Wild—his latest, most ambitious book to date. “All that matters in my whole life are those pictures in Wild,” Nichols told Sierra.

Nichols began his career at GEO magazine in the 1980s, shooting the rugged terrain of caves for 10 years. He became known for his edgy style, and National Geographic took notice. In 1996, the magazine hired him as a staff photographer, and in 2008, he became its editor-at-large for photography. He stayed at National Geographic for the rest of his career, pushing the envelope of the magazine’s creative direction. Now retired, Nichols has chronicled his legacy in Wild.

Weighing seven pounds, Wild is composed of more than 300 pages of photos Nichols took across the years, threading the needle from his days of film photography through his switch to digital. Nichols controlled every aspect of production, from the photos selected to the design choices (there are no captions). “When you thumb through this book and get to the end, you can't help but feel something,” Nichols said. “I wanted that visceral response that you get from not having any information, just the picture. That was really important to me.”

Having worked with publishers in the past who compromised his vision, Nichols sought alternative lines of production. “I didn't want to have to deal with a publisher or somebody that was trying to make a product out of it,” he said, which led him to Books for Friends, an Austria-based publisher known for giving artists full editorial autonomy. The book was entirely funded through advance sales on Instagram, on which Nichols posted all of its photos. Customers didn’t receive a copy until a year and a half later. “I didn't do it for the masses,” he said. “I did it for an audience that knows my work and cares about it.”

Newborn, Dzanga Bai, Central African Republic, 1993

Recollecting his days out in the field, Nichols admits that the most challenging part was working with scientists. He joined them on their research excursions into remote corners of the world, from climbing towering redwood canopies in California to following the migration of elephants in Kenya. But despite the fact that they shared the same mission—to protect wildlife at all costs—there was a distinct power imbalance. Scientists didn’t always take Nichols’s work seriously, which left Nichols feeling frustrated. Scientists worked on tight schedules, leaving no time for Nichols to linger for that quintessential shot; his creative process was bound by their demands. “They didn't see that I was just as driven as they were,” Nichols said. “They would have spent 20, 30 days in the tree if it was for the research. But for just a picture? That was hard.”

“I'm going to kill myself to get the picture. And I'm going to take the time to get it.”

Self-portrait, Republic of Congo, 1999

Frustrating as it was, collaborating with scientists was also the most rewarding part of the job. Nichols worked on Brutal Kinship with primatologist Jane Goodall, a book that illuminates the relationship between apes and humans, and documented a 465-day expedition across the Congo Basin led by ecologist Mike Fay in The Last Place on Earth. These books, alongside scientific research, were extremely influential, informing US policy debates on what to do with retired chimps used in biomedical research trials and raising over $65 million for the establishment of 13 national parks in Gabon.

Nichols’s notoriety came at a personal cost, though. He’s been married to his wife for over 40 years and has two sons. To this day, he apologizes for not being there for them as much as he should have. A career in photography demands a single-minded selfishness, he lamented.

In his three decades as a photographer, Nichols has witnessed a tremendous amount of change in the industry. Lately, he finds himself worrying about the corporatization of photography. When Nat Geo was a nonprofit, the institution invested heavily in the work of artists. But when Disney acquired it, the money, and thus the quality of work, disappeared. “Every kind of photography requires a nonprofit mentality,” Nichols said. “Because if you're going for-profit, you're selling a different story.”

Nowadays, procuring money for photography trips is difficult. Young photographers are required to enter unpredictable financial arrangements, whether that be through part-time side gigs or crowdfunding campaigns. “There’s a lot of distraction involved with trying to get the money,” Nichols said. The solution? “Philanthropy might be what saves us. There's a lot of rich people in the world,” he said wryly.

Still, Nichols believes that the art of wildlife photography must continue. He advises aspiring photographers to first obtain a strong liberal arts education, which is critical to discovering their unique voice. Then, they will need an unwavering devotion to the craft (and a healthy dose of arrogance).

“When you’re between 18 and 27, that's when you have to subjugate yourself,” Nichols advised. “That's when you literally do whatever it takes to learn about what you're going to do, because then you're going to start maturing. When you reach that maturity of imagery, maturity of writing, and maturity of voice, you're able to go out and do the work.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club