A Photographer Zooms Out to Reveal Hidden Costs of the Anthropocene

J Henry Fair captures industrial sites from the sky

Photos by J Henry Fair

J Henry Fair has always been fascinated with discarded objects. While growing up in Charleston, South Carolina, he began taking photographs of rusty wheels, gears, and other mechanical castoffs. Soon, the self-described engineer, scientist, activist, and artist was photographing entire industrial sites, first from the land and later from the sky.

Today, Fair is determined to capture the Anthropocene, the term many experts use to define our current geological epoch: an era of human-driven planetary transformation and insatiable desire for consumption. His aerial portraits of factory discharge and mine byproducts represent the hidden costs of modern life.

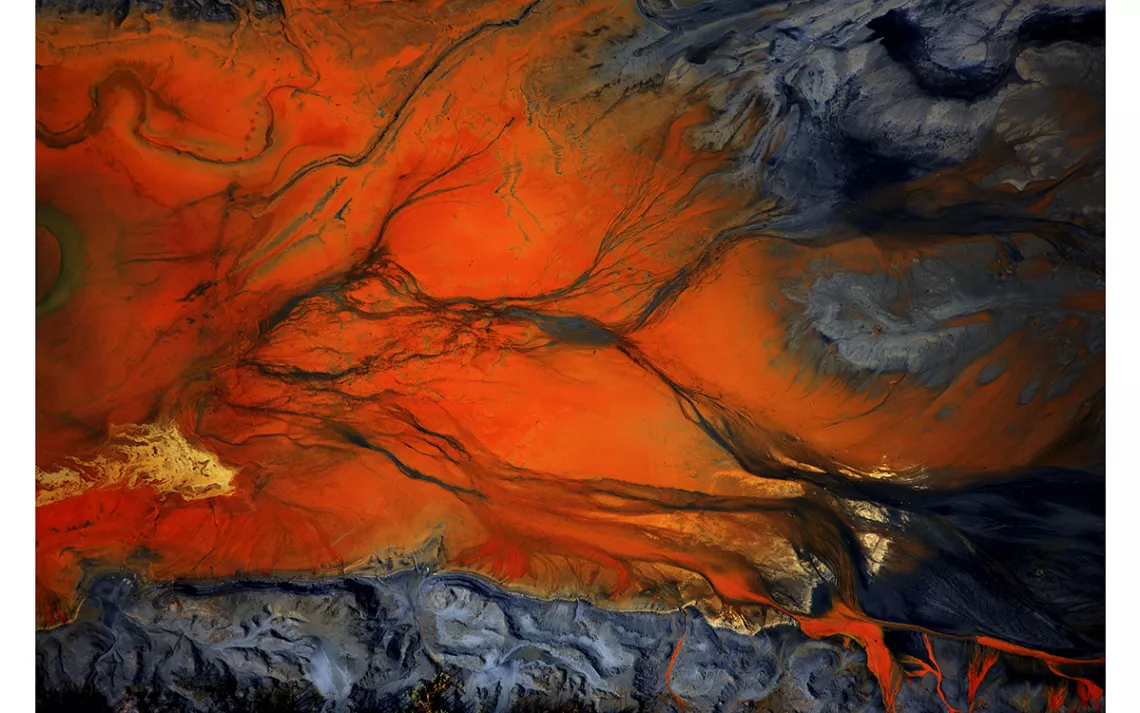

Fair’s series chronicling the devastating waste of coal ash—the byproduct left behind after burning coal for fuel—is an appeal to the gut. Coal ash is visually striking, especially from above. The abstractness and beauty of his images pique viewers’ curiosity and lead to conversations about the harms they represent.

“If [people] see that swirling picture of red and black, they say, ‘Wow, what is that?’ And then I can say, ‘Well, in fact, that's coal ash,’” Fair told Sierra.

In his latest book, On the Edge: Combahee to Winyah (Papadakis, 2019) Fair focuses on coastlines imperiled by climate change and the existential threat of rising seas in South Carolina. Fair is also one of 12 nature and conservation photographers featured in Human Nature (Chronicle Books, 2020), an examination of present-day environmental crises.

Fair has been grounded by the COVID-19 pandemic, but he’s continued to add new sites to his list of future shoots and hopes to return soon to the coasts. With all his work, most notably through his series on coastlines, Fair strives to convey the urgency of climate change.

He views his camera as an opportunity to stoke an emotional connection between his readers and a planet in crisis—an educational tool in a propaganda war between fossil fuel companies and environmentalists, where emotion can often be more convincing than brute fact.

“We in the science and environmental world make the mistake of thinking that if we give you more facts, you’ll understand,” he says. “But no, that’s not how it works. People don’t get facts. People get emotions.” He thinks fossil fuel companies have historically had more success harnessing those emotions.

Fair was inspired to take up his signature photography style during a red-eye flight across the United States. Shortly after sunrise, he looked out the window to see the tops of smokestacks protruding from the shore of a river blanketed in fog. He snapped a photo, then took to the sky in search of similarly enthralling scenes, enlisting the help of conservation aviation groups Southwings and LightHawk.

Photo courtesy of Dirk Vandenberk

“I think irony works, and that’s why I make beautiful pictures of toxic waste,” he says.

Fair usually scouts the locations online ahead of time. By the time he’s airborne, he knows exactly what he wants to capture. The shoots themselves are high-energy, high-stress ordeals: As the plane approaches the site, Fair gives verbal directions to the pilot, who is also talking to air traffic control to get permission to be in the area. Meanwhile, Fair is constantly checking his camera, making sure the turbulence hasn’t changed the settings.

Once the plane is in position, he leans out the window with his camera, visualizing the image he wants to capture. The wind outside roars so loudly that he has to turn off his microphone and can’t communicate with the pilot during those critical moments. That same wind often blows the plane out of position, forcing them to circle around and do it all again.

In the meantime, Fair looks on, checking and rechecking his camera, waiting for the instant when the scene below perfectly represents the story he’s come to tell.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club