Welcome to SharkFest 2020

Who needs the Olympics when there's the … sharklympics?

Olympic athletes’ ultimate pinch hitters? The greatest athletes to be found in the ocean, of course. Tomorrow kicks off SharkFest, a.k.a. National Geographic and Nat Geo Wild’s annual celebration of the 400-million-year-old apex predators that managed to outlive dinosaurs. In its eighth year, the five-week-long viewing bonanza is extra epic, with 17 original specials—starring several among the 1,000+ species of sharks out there—plus shark-centric favorites from the Nat Geo archives, airing across both networks.

In addition to SharkFest stalwarts like When Sharks Attack (which aims to decode the mystery of why these apex predators suddenly strike), SharkFest 2020 features new programming like World’s Biggest Tiger Shark?, in which a marine biologist and cinematographer suit up in diving gear and quest to French Polynesia in pursuit of Kamakai, the world’s largest tiger shark (and learn a lot about the majestic creatures’ cooperative hunting tactics along the way). Other fresh programming examines sharks’ complex relationships with fellow ocean denizens (see: Sharks vs. Dolphins: Blood Battle) and with human adventurers (Shark vs. Surfer). We’re especially psyched for Sharkcano, which examines the link between, you guessed it, sharks and volcanoes. In a hair-raising and visually dazzling mission, shark biologist Dr. Michael Heithaus ventures to volcanoes across the globe in an attempt to figure out why the eponymous stars of the show are so drawn to this other fearsome force of nature.

2020 is looking to be a singular year for shark scientists. According to Heithaus, the pandemic has resulted in many more sharks swimming in places that used to see much more boat traffic. “We’re starting to see what nature can look like with lower levels of disturbance, which could drive people to make the changes necessary to restore populations of animals closer to the right levels, where they used to be.”

Sharks are crucial to marine ecosystems, but not surprisingly, recent years’ global warming and ocean acidification have posed unprecedented challenges. “In terms of where they live and how they move, a lot of sharks are tied to temperature ranges,” Heithaus told Sierra. “A lot of sharks that used to live closer to the equator have moved, and we still don’t know how much acidification is disrupting food chains. But the good news is, marine ecosystems are pretty resilient. They can bounce back; we just have to help them do that.”

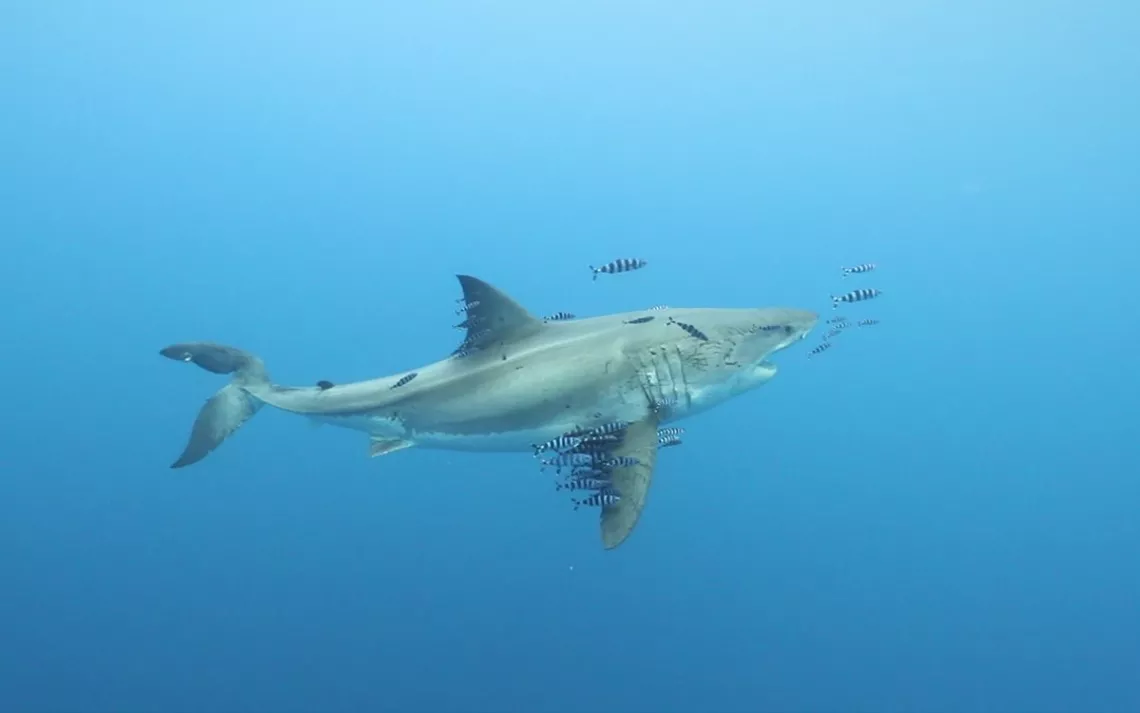

The fest begins tomorrow evening at 6/5 P.M. Central. Until then, please enjoy this photographic showcase, featuring the splendor of 14 among SharkFest’s stars.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club